The desert is a place of paradox—a realm where life exists on the edge of death, and where survival is a daily act of quiet defiance. Beneath the searing sun and across landscapes that shimmer with heat, an astonishing array of creatures endures. Their world is one of scarcity, where temperatures soar beyond the limits of most life and water is as rare as diamonds. Yet despite these extremes, the desert pulses with life—hidden, watchful, and exquisitely adapted.

From the iconic camel traversing sand dunes to the inconspicuous kangaroo rat burrowing beneath the earth, desert animals have evolved in remarkable ways. Their adaptations are not just physical, but behavioral and biochemical, each finely tuned by evolution to solve the harsh equations of heat, drought, and predation. In the silence of the desert, there is brilliance—natural engineering so elegant that it borders on the miraculous.

Heat as a Shaping Force

At the core of desert survival lies an unrelenting force: heat. Desert animals do not simply resist it; they have evolved strategies to coexist with it, avoid it, or, in some cases, exploit it. In regions where surface temperatures regularly exceed 45°C (113°F) and can climb beyond 70°C (158°F) on the ground, thermoregulation is not optional—it is vital.

Physiologically, desert animals manage heat through multiple avenues. Many exhibit a high tolerance for body temperature fluctuations that would be lethal in other species. Camels, for instance, can withstand body temperatures ranging from 34°C to over 41°C (93°F to 106°F), reducing the need for evaporative cooling, which would deplete precious water. Their thick fur, counterintuitively, insulates them from both heat and cold, buffering them against daytime extremes and nighttime chills.

Reptiles, often the symbolic inhabitants of the desert, leverage their ectothermic nature—regulating body temperature through external sources. Rather than fighting the heat, they bask in it strategically, retreating to shaded burrows when temperatures peak. Sidewinder rattlesnakes use their unique sideways motion to minimize contact with the hot sand, reducing the transfer of heat to their bodies.

Even small mammals have extraordinary thermoregulatory tricks. The fennec fox of North Africa uses its enormous ears not only to detect prey but to dissipate heat through a dense network of blood vessels. Meanwhile, desert gazelles can allow their brain to remain cooler than their core body temperature by utilizing a counter-current heat exchange system in the blood vessels of the head—an innovation that prevents overheating during exertion.

The Art of Evading the Sun

While some desert creatures evolve to withstand heat, many have mastered the art of avoiding it. Behavioral adaptations are as critical as physiological ones, and in the desert, timing is everything.

Nocturnality is the desert’s most widespread solution to daytime heat. Rodents, insects, and even large predators like the desert fox or leopard often become active only after sunset. Under the cover of night, temperatures plummet, and activity becomes less energetically costly and less risky in terms of dehydration.

Burrowing is another key strategy. Beneath the surface, temperatures remain far more stable than aboveground, often cooler by 20–30 degrees Celsius. Many animals dig intricate tunnel systems, where they rest during the day and emerge at dusk. The spadefoot toad, for example, may remain underground for months or even years, entering a state of estivation—a form of dormancy triggered by heat and drought—emerging only after heavy rains.

Some creatures exploit microclimates within the desert. The Namib Desert beetle collects water from fog by facing into the wind on dune crests, allowing condensation to form on its back and drip into its mouth. It does this in the early morning when temperatures are low and humidity is high—a narrow window of opportunity that it has evolved to exploit with impeccable timing.

Water: The Desert’s Rarest Treasure

If heat is a relentless challenge, water is a disappearing dream. Yet desert animals must drink—or find ways not to. Water is essential to life, but in the desert, obtaining it requires extraordinary adaptations.

Some animals absorb water directly from their food. The kangaroo rat, a master of water conservation, never drinks in its entire life. It survives entirely on the metabolic water produced from digesting seeds. Its kidneys are so efficient that they can produce urine five times more concentrated than that of a human, conserving every possible molecule.

Camels can lose up to 25% of their body weight in water—far beyond what would kill most mammals—and still function. When water does become available, they rehydrate at astounding rates, drinking up to 40 gallons (150 liters) in a single session. Contrary to popular belief, they do not store water in their humps; instead, the humps are reservoirs of fat, which can be metabolized into water and energy when needed.

Birds present a unique case: the sandgrouse, found in African and Middle Eastern deserts, soaks its belly feathers in water at an oasis and flies up to 20 miles back to its nest. There, its chicks drink directly from the wet feathers—a touching display of parental care fused with evolutionary ingenuity.

Other species reduce water loss by suppressing perspiration and respiration. The thorny devil lizard of Australia collects dew and rainfall through grooves in its skin that channel moisture to its mouth. Some beetles and ants can harvest water vapor from the air, condensing it using special waxy surfaces on their bodies.

Salt, Sweat, and Survival Chemistry

Maintaining fluid balance in the desert isn’t just about acquiring water—it’s about managing salts and solutes. The intense heat accelerates water loss through evaporation, and in animals that sweat or pant, this can lead to dangerous imbalances in electrolytes.

Desert animals have evolved to either minimize salt loss or tolerate high salt concentrations. Reptiles excrete waste in the form of uric acid, which requires far less water than urea, the nitrogenous waste excreted by mammals. Birds, including desert species like pigeons and falcons, excrete both nitrogen and salt through their cloaca and specialized salt glands near their beaks.

Insects and arthropods have waxy coatings on their exoskeletons that prevent desiccation. Even the spiracles—tiny openings for respiration—can open and close to reduce water loss. Some scorpions go a step further, reducing their metabolism to levels so low that they can survive on a single insect meal for months, conserving both energy and moisture.

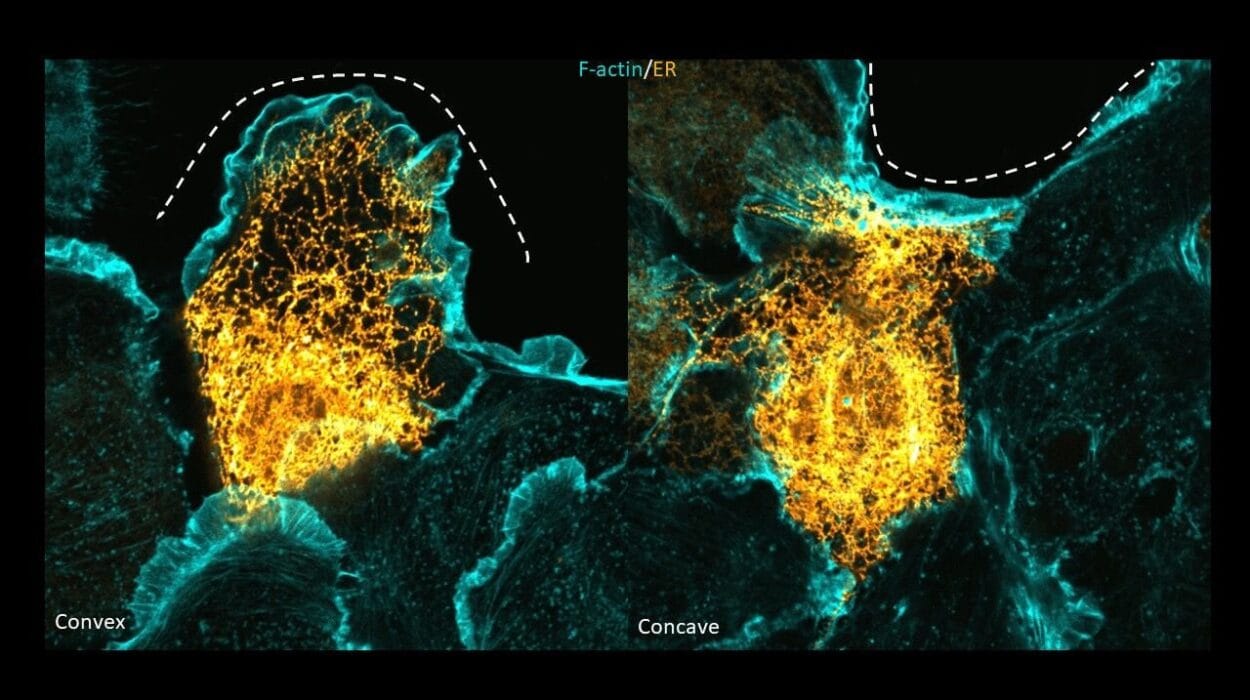

At the cellular level, desert animals exhibit biochemical resilience. Proteins and membranes are stabilized by heat-shock proteins, which are produced in response to rising temperatures and help prevent thermal denaturation. Cells may also accumulate osmoprotectants—molecules like trehalose and proline—that stabilize cellular structures in dehydration.

Color, Camouflage, and Solar Strategy

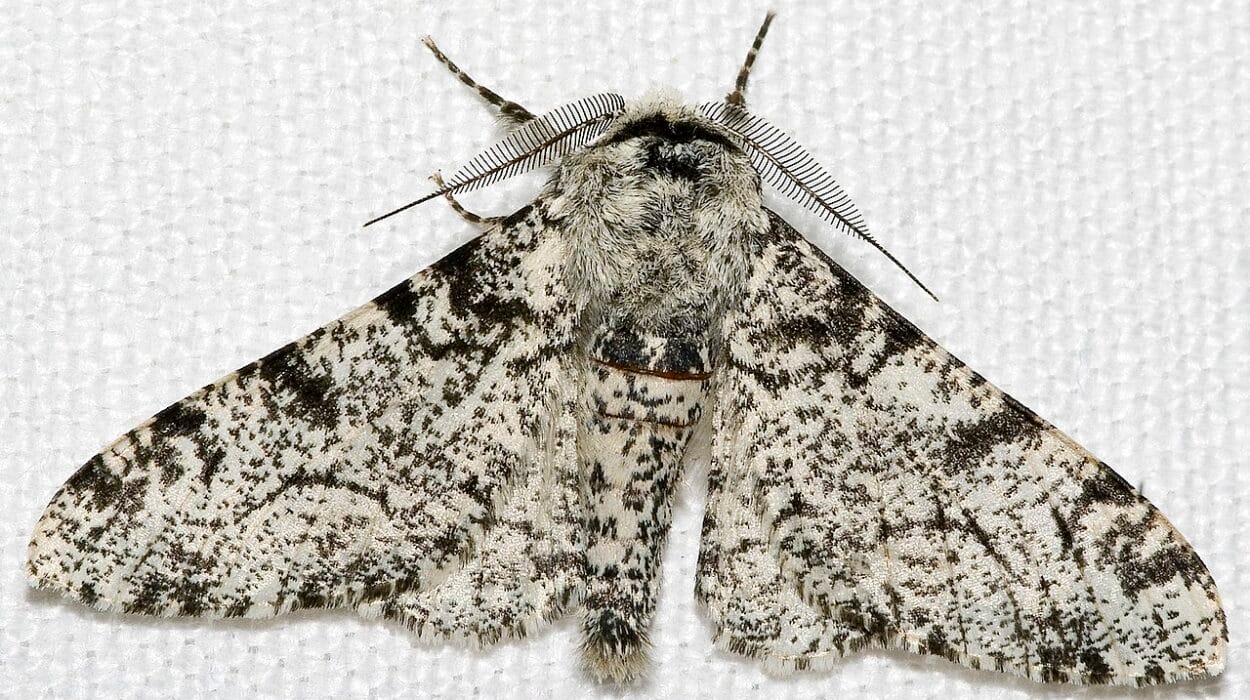

Coloration in desert animals is often more than a matter of concealment; it is a tool of thermal management. Pale colors reflect solar radiation and help animals stay cool. The addax antelope, pale as the sand it walks on, is perfectly camouflaged and well-insulated against the heat.

Some animals change color with the seasons. The rock agama lizard becomes darker during cooler hours to absorb heat more rapidly and paler during hot periods to reflect sunlight. Insects such as certain beetles display iridescence not for aesthetic appeal, but to scatter sunlight and avoid overheating.

Camouflage also serves as a defense against predation. In the flat light of the desert, shadows are long and sparse. Many desert animals have adapted body shapes and behaviors that minimize shadowing and blend them into the terrain. The horned viper buries itself under sand, revealing only its eyes, waiting to strike. Predators, too, like the caracal or desert lynx, wear sandy hues to approach prey unseen.

Breeding, Parenting, and the Rhythm of Rains

Reproduction in the desert is closely synchronized with environmental cues, particularly rainfall. In unpredictable climates, animals must take advantage of brief periods of abundance. Many species exhibit opportunistic breeding, reproducing only when conditions allow their offspring a chance of survival.

Insects, amphibians, and reptiles often lay dormant eggs or enter diapause—a suspended developmental state—until triggered by moisture. The desert locust, for instance, breeds explosively following rains, with swarms that can devastate crops but also represent a spectacular reproductive strategy honed by millennia of boom-and-bust cycles.

Birds like the desert lark or sandgrouse breed in synchrony with the rainy season, when insects and seeds are plentiful. Mammals may delay implantation or adjust gestation in response to environmental signals. Some rodents and marsupials exhibit astonishingly short gestation periods, allowing multiple generations to be born during a single wet season.

Parental care, where it occurs, is deeply invested. Meerkats share the burden of raising pups within cooperative social groups. Some desert frogs dig mud chambers and seal themselves inside with their eggs, maintaining a humid microclimate until rains arrive. Reproductive success in the desert is not just about fertility—it is about timing, resource allocation, and sometimes, sheer chance.

Evolution’s Crucible: Natural Selection in the Desert

The desert is a crucible of evolution, an arena where natural selection operates with brutal efficiency. Mutations and traits that confer even marginal advantages in heat resistance or water conservation can mean the difference between extinction and expansion.

Desert environments, though harsh, are not static. They fluctuate over millennia—wetting and drying, expanding and contracting. As such, desert animals are not only adapted to extremes, but to change itself. Their evolutionary flexibility is part of what allows them to survive in conditions that would annihilate most life forms.

Deserts also serve as evolutionary laboratories. The isolation of oases or dune systems leads to rapid speciation. Unique desert-adapted lineages evolve in parallel—beetles in Namibia and Australia that harvest water with similar strategies, or rodents in North and South America that share kidney efficiencies despite being unrelated.

These convergent adaptations reflect the powerful shaping hand of the environment. In this sense, desert animals are not just survivors; they are the refined products of nature’s most demanding test.

Lessons from the Living Desert

The adaptations of desert animals offer not only biological marvels but also profound lessons for science and sustainability. Biomimicry—learning from nature’s solutions—has led to innovations in water collection technologies, temperature regulation materials, and even architecture.

Engineers have studied the fog-harvesting beetle to design dew-collecting surfaces in arid zones. Architects model passive cooling systems after the burrowed habitats of desert dwellers. Understanding how animals regulate their internal climate, conserve water, and operate under energy constraints can inform human responses to climate change, especially as arid regions expand due to global warming.

Moreover, these adaptations serve as a reminder of life’s tenacity. They show that even in the harshest environments, beauty and complexity can flourish—not in spite of adversity, but because of it.

Echoes Beneath the Dunes

To walk through the desert with a trained eye is to see evidence of life etched into the sand—tracks of a beetle zigzagging between shrubs, the hidden entrance of a rodent burrow, a solitary bird call echoing across the dunes. Each of these marks tells a story of resilience, adaptation, and the unbreakable will to live.

Desert animals are not anomalies or outliers; they are testament to evolution’s brilliance. They demonstrate that survival is not about overpowering one’s environment, but about harmonizing with it, mastering its rhythms, and enduring its tests with quiet, persistent ingenuity.

As the sun sets over the horizon and the desert breathes its cool night air, life stirs beneath the sand and stars. Creatures emerge, not in fear of the dark, but in triumph over the day. They are the keepers of secrets forged in heat, the architects of survival, and the enduring proof that even the most inhospitable places on Earth are filled with wonder.