In the rugged expanse of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, a fossil skull shimmered from the sandstone like a hidden gem. Resting halfway down a cliff face, its smooth dome caught the light like a polished jewel. For the scientists who uncovered it, this was no ordinary find. It was the first glimpse of Zavacephale rinpoche—a newly named species of pachycephalosaur that is already rewriting the evolutionary history of this mysterious dinosaur group.

Described in the journal Nature, the fossil is not just scientifically significant; it’s breathtaking. It is the most complete skeleton of a pachycephalosaur ever discovered, and at 108 million years old, it pushes back the fossil record of these dome-headed dinosaurs by at least 15 million years.

For paleontologists, this is more than just a fossil. It is a missing chapter of dinosaur history, one that sheds light on how pachycephalosaurs grew, lived, and evolved.

Meet the Pachycephalosaurs: Dinosaurs of the Dome

Pachycephalosaurs are some of the most iconic yet puzzling dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. They are instantly recognizable for their thick, rounded skull domes—bony helmets that could reach more than 25 centimeters (10 inches) thick. Popular imagination often portrays them as prehistoric gladiators, ramming each other like mountain goats in fierce contests of dominance.

But despite their fame, they remain elusive in the fossil record. Most known specimens are just isolated skull fragments, often weathered and incomplete. Their skeletons are rare, and their evolutionary origins have been shrouded in mystery.

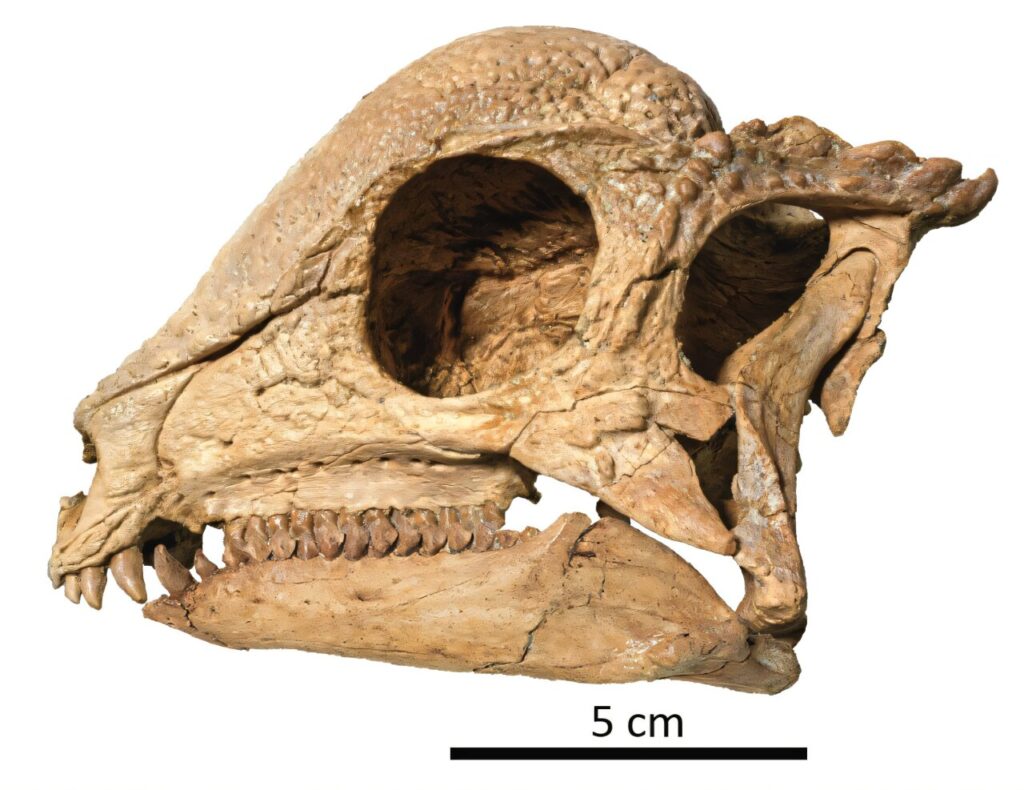

This is what makes Zavacephale rinpoche—nicknamed the “precious one”—so extraordinary. For the first time, scientists can pair a nearly complete skeleton with a fully domed skull, giving them a clearer picture of how these strange dinosaurs developed and lived.

The Discovery in the Gobi Desert

The discovery took place in the Khuren Dukh locality of Mongolia’s Eastern Gobi Basin, an area rich with fossils that whisper stories of long-lost ecosystems. Lead author Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences, alongside an international team of researchers, uncovered the remarkable specimen.

When this dinosaur roamed the Early Cretaceous landscape around 108 million years ago, the Gobi was not the barren desert it is today. Instead, it was a lush valley dotted with lakes, bordered by cliffs and escarpments. Here, Zavacephale rinpoche browsed on vegetation, sharing its world with other dinosaurs in an environment that teemed with life.

The fossil revealed something astonishing: the animal was still a teenager, not fully grown, yet it already bore a complete, rounded dome. Unlike later pachycephalosaurs with ornate skull ornamentation, Z. rinpoche’s head was simple but fully formed, offering crucial insight into how these dinosaurs developed their distinctive domes.

A Teenager With a Dome

To determine the age of the specimen, researchers examined a thin slice of its lower leg bone, much like counting tree rings to estimate age. The analysis revealed that the dinosaur was not yet an adult when it died. And yet, it had already grown its signature dome.

This discovery challenges assumptions about pachycephalosaur growth. Paleontologists have long debated whether differences in skull shape between fossils represented distinct species or merely growth stages. The fact that a juvenile already had a dome suggests that ornamentation appeared early in life, before maturity.

Lindsay Zanno, paleontologist at North Carolina State University and coauthor of the study, puts it succinctly: “Pachycephalosaurs are all about the bling—but we can’t rely on ornamentation alone to identify species, because it changes as they grow.” With Zavacephale rinpoche, researchers now have a baseline to understand how the domes developed across life stages.

More Than Just a Skull

Most pachycephalosaur fossils are frustratingly fragmentary—just pieces of skull domes scattered across prehistoric sediments. But Z. rinpoche gives us far more. Its skeleton includes limbs, hands, an articulated tail reinforced by stiffening tendons, and even stomach stones (gastroliths) that helped grind up plant material.

Z. rinpoche skull. Credit: Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig

These details are revolutionary. They reveal that pachycephalosaurs weren’t just about flashy headgear—they had distinctive body plans, dietary strategies, and locomotion styles that we are only now beginning to understand.

The articulated tail, for instance, suggests these dinosaurs had stiff, counterbalancing tails that may have helped them maneuver while moving on two legs. The stomach stones confirm their herbivorous diet and hint at a digestive system adapted to tough vegetation. For a group once defined almost entirely by their skulls, this is a rare and invaluable glimpse at their whole biology.

Life and Behavior of Zavacephale rinpoche

Though Z. rinpoche was only about 3 feet (1 meter) long when it died, adults of later pachycephalosaurs could grow up to 14 feet (4.3 meters) and weigh nearly 900 pounds (410 kilograms). These were not predators but plant-eating dinosaurs, quietly grazing yet still competing for attention and mates.

So why the dome? According to researchers, the thick skulls likely served as socio-sexual display structures—tools for attracting mates or intimidating rivals, much like the antlers of deer or the bright plumage of birds. The popular image of pachycephalosaurs headbutting like rams may not be entirely accurate, but their domes were certainly built for display and competition.

As Zanno quipped, “If you need to headbutt yourself into a relationship, it’s a good idea to start rehearsing early.” And Z. rinpoche, with its teenage dome, may have been doing just that.

Rewriting the Pachycephalosaur Timeline

Perhaps the most profound impact of this discovery is temporal. Until now, pachycephalosaurs were thought to appear later in the Cretaceous. But Zavacephale rinpoche pushes their origins back by at least 15 million years.

This means that pachycephalosaurs were experimenting with their signature domes much earlier than scientists realized. It fills a major gap in the fossil record, showing that the evolutionary story of these dinosaurs began long before their later, more elaborate relatives emerged.

“This specimen is a once-in-a-lifetime discovery,” says Zanno. “Not only is it the oldest definitive pachycephalosaur, but it’s also the most complete and beautifully preserved. It gives us an unprecedented window into how these dinosaurs grew and lived.”

A Window Into Deep Time

In the end, Zavacephale rinpoche is more than a fossil—it is a time capsule. From its sturdy legs to its jewel-like dome, it tells us how a lineage of dinosaurs first began to shape their strange and striking identities.

It reminds us that even in one of the world’s most barren landscapes, the past is still waiting to be uncovered, piece by piece, bone by bone. Each discovery is a reminder that the Earth’s history is still being written, and that our understanding of life’s grand narrative is forever expanding.

In the quiet rocks of the Gobi Desert, a teenage dinosaur has spoken across 108 million years, answering questions we never thought could be answered—and raising new ones we cannot yet imagine.

More information: Lindsay Zanno, A domed pachycephalosaur from the early Cretaceous of Mongolia, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09213-6. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09213-6