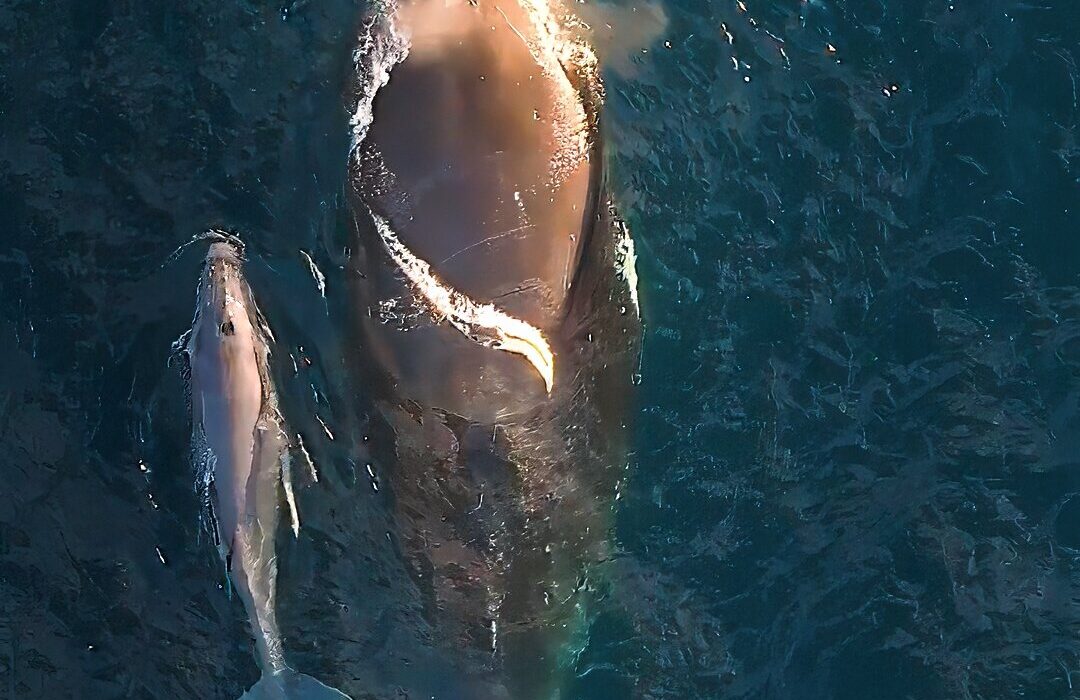

If you stood on the edge of a rocky coastline today, watching a humpback whale breach the surface, its massive body slicing through sky and sea, it might feel impossible to imagine this elegant creature as anything but aquatic. Yet deep in Earth’s geological past, before the oceans echoed with their haunting songs, whales walked. Their ancestors trod upon solid ground, breathed air with no threat of water overhead, and sniffed the wind instead of diving beneath waves. The story of whale evolution is one of the most extraordinary and well-documented transitions in the history of life—an epic journey from land to sea that took place over tens of millions of years, leaving behind a fossil trail that defies belief.

This story isn’t just about how whales became whales. It’s about how nature, through the slow hand of evolution, can transform the impossible into reality. It’s about the persistence of life in the face of changing environments and the boundless creativity of evolution when confronted with the challenges of survival.

The Ancestors Walked on Four Legs

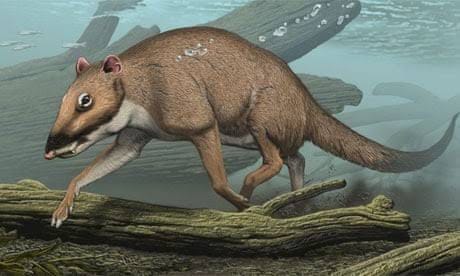

About 50 million years ago, during the early Eocene epoch, the world was a different place. The continents were still shifting into their modern positions, the climate was warm, and mammalian life was diversifying rapidly in the aftermath of the dinosaurs’ extinction. Somewhere in what is now the Indian subcontinent or Pakistan, a curious creature lurked near freshwater rivers. It was not a whale—not yet—but it was a close relative. This animal, later named Pakicetus, had the unmistakable body of a land-dwelling quadruped, with long legs, a tail, and ears adapted for hearing in air. But look closely at its skull, and the hints begin to emerge: the thickened auditory bulla, a bony structure found in modern whales, was already present. Evolution had started whispering of change.

Pakicetus probably hunted fish along riverbanks, spending time in shallow water, perhaps wading or even paddling. It was a predator, sharp-toothed and agile. Yet, its very bones were already betraying a future far from the land it walked.

As paleontologists uncovered more fossils, a clearer picture began to form. Another genus, Ambulocetus, meaning “walking whale,” was unearthed in similar regions. This remarkable animal looked like a blend of crocodile and otter—thick-limbed, capable of walking and swimming. Its hind legs were powerful, and its spine was flexible, allowing for a swimming style that mirrored modern otters or seals. Ambulocetus could not only stalk prey on land but also launch itself into rivers or coastal shallows with surprising grace. Here was a true transitional form, a creature suspended between two worlds.

Adaptations for an Aquatic Life

As whales’ ancestors began spending more and more time in the water, their bodies responded in kind. Over millions of years, their limbs changed shape, their skulls morphed to accommodate different senses, and their internal organs followed suit. The nose crept up the skull, eventually becoming the blowhole at the top of the head. Ears evolved to better receive vibrations underwater. The legs shrank, the tails broadened, and flukes—horizontal tail fins used for propulsion—developed.

One of the most telling fossils from this era is Rodhocetus, a creature that retained strong hind limbs but had a more streamlined body, ideal for swimming. It had evolved an elongated tail and stronger vertebral column—features suggesting it was now using undulating spinal movements to swim, just like dolphins do today. The pelvis was still connected to the spine, so Rodhocetus could technically walk on land, but it likely did so clumsily. The water was becoming its true home.

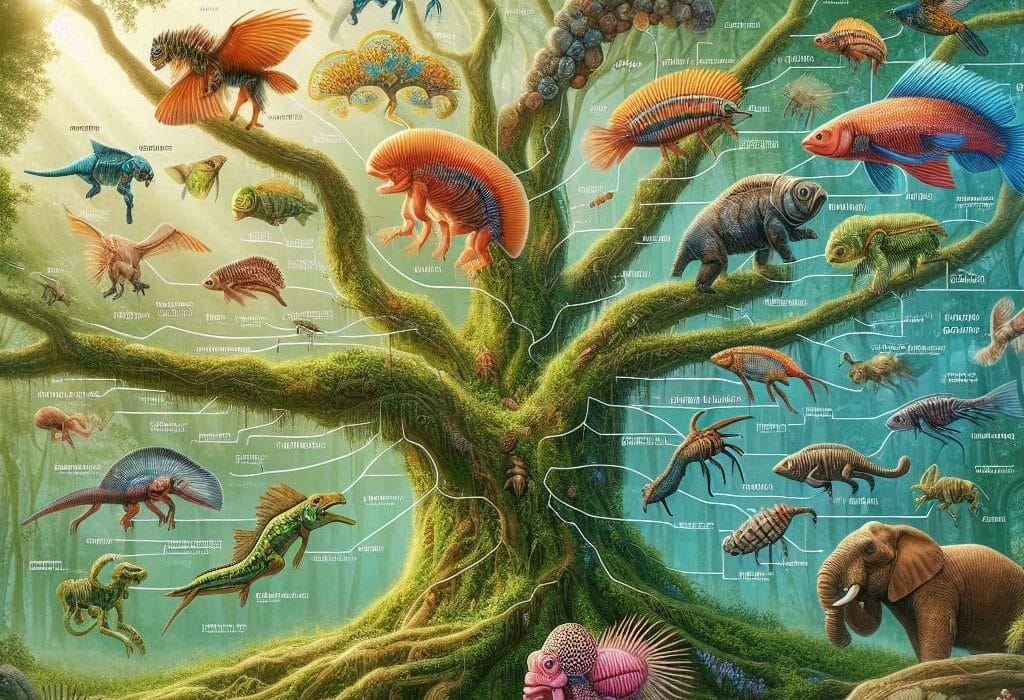

These intermediate whales were not just evolutionary curiosities. They were the prototypes, the blueprints for a future that held titanic blue whales and acrobatic orcas. Their bones, buried and fossilized across ancient seabeds and sediments, tell us that evolution is not a leap, but a slow, grinding transformation—a sculpting of form and function driven by time, mutation, and natural selection.

The Open Ocean Beckons

By about 40 million years ago, during the middle Eocene, whales had begun to sever their ties with land almost completely. A major player in this phase was Basilosaurus, a genus of long, serpentine whales with fully aquatic bodies. At up to 60 feet long, Basilosaurus was one of the first true leviathans of the sea. Its hind limbs had shriveled into tiny vestigial limbs—useless for walking but fascinating for what they represent: relics of a terrestrial past.

Though Basilosaurus looked much like a modern whale, it swam with a sinuous, snake-like motion, and its skull bore sharp, conical teeth perfect for slicing through flesh. This was a predator adapted to life in the open ocean, no longer bound by the need to return to shore. It gave birth to live young, possibly tail-first, an adaptation that prevents newborns from drowning at birth—a crucial step for marine mammals.

The fossil record also introduces us to Dorudon, a smaller cousin of Basilosaurus, more compact in size but equally adapted for aquatic life. Their skeletons show that modern whale features—streamlined bodies, powerful tails, and specialized skulls—had become fully established.

But a transformation was also occurring on the inside. Whales’ kidneys adapted to deal with saltwater, their lungs evolved to exchange gases rapidly during brief surface visits, and their echolocation abilities began to emerge. In a remarkably short evolutionary window, whales had gone from hoofed land animals to deep-diving, echolocating ocean titans.

The Split: Toothed and Baleen Whales

By 34 million years ago, the Eocene was ending, and with it came a pivotal moment in whale evolution: the divergence of whales into two distinct lineages—those that would evolve baleen and those that would develop sophisticated echolocation.

Toothed whales, or odontocetes, include dolphins, sperm whales, orcas, and narwhals. These creatures retained their teeth and became the acoustic specialists of the deep. Through a complex nasal system, they developed echolocation—the ability to use sound waves to navigate and hunt in the dark ocean. This adaptation gave them an edge in murky or deep waters, where eyesight fails.

Baleen whales, or mysticetes, took a different path. Rather than hunt large prey, they evolved baleen plates—comb-like structures that filter small organisms like krill and plankton from the water. This was an evolutionary bet on abundance. Instead of expending energy chasing prey, these giants could consume massive quantities of small creatures by simply opening their mouths. The blue whale, the largest animal ever to live, survives on tiny shrimp-like krill—an evolutionary paradox that underscores the efficiency of filter feeding.

Fossils of ancient baleen whales show a transitional stage where teeth and baleen coexisted. Eventually, natural selection favored baleen over teeth, and today, mysticetes are entirely toothless.

Whales Today: Echoes of Evolution

Modern whales are marvels of adaptation. They are warm-blooded, breathe air, give live birth, and communicate in complex vocal patterns. Yet inside their vast bodies lie the secrets of their land-dwelling past. Vestigial pelvic bones remain, buried beneath layers of blubber, serving no purpose in locomotion but speaking volumes about their ancestry. Embryonic whales briefly grow tiny hind limbs, which disappear before birth—echoes of a terrestrial heritage whispered in developmental time.

Their spinal columns reflect the powerful swimming motions of their ancestors. Their blowholes are not random adaptations but the result of a slow migration of the nostrils up the skull. Even the structure of their flippers reveals finger bones—the five-digit plan of terrestrial vertebrates, now hidden inside fins instead of grasping branches or walking on soil.

And then there is their mind. Whales, especially species like dolphins and sperm whales, exhibit intelligence, social complexity, and even signs of culture. Some scientists propose that the challenges of navigating and surviving in the three-dimensional oceanic world may have driven the evolution of large brains and complex behaviors.

A Story Still Being Written

For much of the 20th century, the story of whale evolution remained fragmented. Darwin himself had speculated that whales might have descended from bears that took to the water, a hypothesis we now know to be off course. But with the discovery of transitional fossils like Pakicetus, Ambulocetus, and Basilosaurus, the narrative solidified into a coherent, awe-inspiring timeline. Molecular biology has since confirmed the connection: DNA analysis shows that whales are most closely related to hippos, their closest living relatives. Both descend from a group of hoofed animals called artiodactyls—creatures that walked on even-toed hooves and include pigs, deer, and cows.

Today, paleontologists continue to discover new fossils that refine our understanding of this evolutionary journey. Each bone dug from ancient riverbeds or seabeds brings new clarity, not just about whales, but about how life evolves, adapts, and endures.

Human Witness and Responsibility

There’s something profoundly moving about watching a whale breach or glide beneath a boat—something that stirs a deep, primal awe. Perhaps it’s because these creatures, so different from us, still mirror us in essential ways: they breathe as we do, raise families, sing, mourn, and play. Their story is not just a scientific curiosity—it’s a shared inheritance. We too are products of evolution, shaped by the pressures of survival and the reach of time.

But that story is now endangered. Industrial whaling, pollution, ship strikes, and climate change have pushed many whale species to the brink. Despite international protections, some populations are dwindling, and entire migration routes are threatened by human noise, sonar, and warming waters.

Understanding the evolutionary journey of whales isn’t just an intellectual exercise—it’s a call to stewardship. These animals have survived epochs, ice ages, extinctions, and planetary upheavals. To see them vanish in our lifetime would be to silence a story 50 million years in the making.

A Legacy That Survives the Depths

From walking on land to dancing in the ocean’s blue embrace, whales have become among the most iconic and mysterious creatures on Earth. Their journey—etched into bones, genes, and the fluid poetry of their movement—stands as one of the greatest stories evolution has ever told. A tale of change, of adaptation, of survival against all odds.

Their breath is our breath. Their journey is our journey. And as long as whales still swim through the oceans, the Earth retains a piece of its ancient magic.