As humanity sets its sights back on the Moon, the focus isn’t solely on dusty footprints and flags. This time, the lunar surface may serve as a springboard to the deepest questions ever asked about our cosmos. In the coming decades, the Moon is set to host not just astronauts and habitats, but scientific instruments designed to tune into the silent whispers of the early universe—long before stars were born, galaxies took shape, or light bathed the cosmic landscape. Among these visionary instruments is the Dark Ages Explorer (DEX), a European proposal to transform the far side of the Moon into the quietest and most profound radio observatory ever conceived.

The Moon as the Next Scientific Frontier

In the 2020s and 2030s, a coalition of global space agencies—NASA, ESA, China’s CNSA, Roscosmos, and their commercial counterparts—are converging on a bold idea: the Moon not just as a waypoint, but as infrastructure. With projects like NASA’s Artemis Base Camp and Lunar Gateway, the ESA’s Moon Village, and the Chinese-Russian International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), the once barren lunar surface is poised to become an interplanetary laboratory.

These programs are far more than flag-planting exercises. They include permanent installations and scientific platforms that could revolutionize astronomy, physics, biology, and planetary science. Among the most tantalizing possibilities? Turning the far side of the Moon—shielded from Earth’s noisy radio transmissions—into a pristine observatory for radio astronomy, capable of peering into the universe’s darkest, most mysterious epoch: the Cosmic Dark Ages.

Probing the Silent Cosmos

Roughly 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe underwent a phase transition known as Recombination, when electrons and protons cooled enough to combine into neutral hydrogen atoms. This allowed the release of the first light in the universe—the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB)—a dim afterglow of the Big Bang that telescopes like Planck and WMAP have since mapped with stunning precision.

But beyond that luminous veil lies a cosmic silence. A stretch of time from about 380,000 years to nearly one billion years after the Big Bang—known as the Cosmic Dark Ages. During this time, the universe was a murky ocean of hydrogen gas, devoid of stars or galaxies, lightless and opaque. It’s a chapter of the universe’s history we’ve barely scratched.

That began to change during the Cosmic Dawn (ca. 50 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang), when gravity drew clumps of hydrogen together to ignite the first stars. Their ultraviolet light began reionizing the hydrogen around them, eventually ending the Dark Ages and lighting up the cosmos in earnest.

But how did this process begin? How fast did structures—galaxies, stars, black holes—emerge? What role did dark matter play? These are among the most urgent and elusive questions in cosmology.

The 21 cm Hydrogen Line: A Cosmic Fossil

The key to unlocking these ancient mysteries lies in a faint radio signal: the 21-centimeter emission line produced by neutral hydrogen atoms. When hydrogen atoms flip the orientation of their electron and proton spins, they emit photons at a very specific radio frequency—1420 MHz. As the universe expanded, this signal became redshifted, stretched into longer wavelengths and lower frequencies.

Today, the original 21 cm signal from the Cosmic Dawn and Dark Ages would be visible at ultra-low radio frequencies—below 100 MHz, even below 30 MHz for the earliest epochs. Unfortunately, these frequencies are almost completely absorbed by Earth’s ionosphere and are also polluted by human-made radio frequency interference (RFI).

That’s why the far side of the Moon is ideal. It’s a radio-quiet zone, permanently shielded from Earth’s transmissions. No internet, no phones, no television signals—only silence. It’s the perfect place to listen for the softest echoes of the infant universe.

Enter the Dark Ages Explorer (DEX)

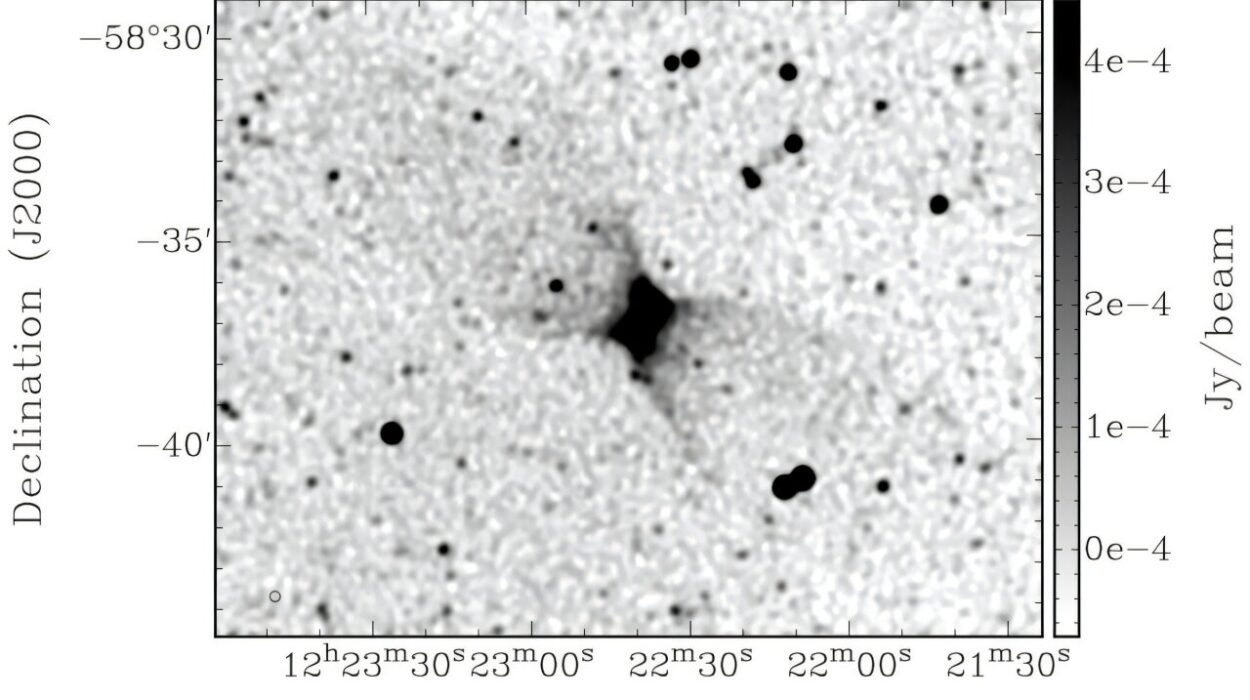

An ambitious concept proposed by Christiaan Brinkerink of Radboud University and a consortium of European institutions, the Dark Ages Explorer (DEX) is a lunar-based radio interferometer designed to detect the 21 cm hydrogen line from the Cosmic Dawn and even the Dark Ages. This novel telescope aims to construct a radio “movie” of the universe’s evolution before and during the birth of stars.

Backed by organizations like ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, and researchers from Cambridge, Leiden, and ESA’s ESTEC, DEX proposes a network of antennas that would spread across a 200-by-200-meter area on the lunar far side.

According to Brinkerink, DEX’s mission is simple in theory, but profound in implication: measure the spatial power spectrum of the 21 cm signal across time. In practice, this would mean scanning different “slices” of redshifted hydrogen emissions, from z = 14 to z = 50, revealing how early matter clumped together to form stars, galaxies, and possibly the seeds of supermassive black holes.

Why We Need DEX

Existing telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have made astonishing discoveries—finding surprisingly mature galaxies just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. These galaxies are brighter and more numerous than expected. Webb also observed massive black hole precursors at early epochs, suggesting that our standard models of galaxy and structure formation might be missing a critical ingredient.

This mismatch—what cosmologists call tension—indicates a gap in our understanding of how the early universe unfolded. It suggests there may be unknown physics at play, perhaps involving dark matter, exotic forms of energy, or feedback mechanisms we haven’t yet modeled.

The only direct window into this era is through the 21 cm signal. Instruments like EDGES (Experiment to Detect the Global Epoch of Reionization Signature) have already hinted at unexpected features—like an absorption signal twice as deep as predicted. But to map this signal with clarity and precision, far from Earth’s noisy influence, we need a facility like DEX.

Engineering on the Edge

Building anything on the Moon is no easy feat. DEX’s vision, detailed in a recent study, stems from years of groundwork by ESA’s Astrophysical Lunar Observatory Topical Team (ALO TT), which included scientists and engineers from across Europe. ESA’s 2021 Concurrent Design Facility study concluded that while a 4×4 antenna array was possible with current tech, the real scientific payoff would require a 32×32 array—more than 1,000 antennas deployed with extreme precision.

Such a system requires flat terrain, ideally within a crater on the Moon’s far side. One likely location is in the southern polar region, where Artemis missions will focus their attention. This region, while more thermally stable, still experiences swings from 54°C during the day to -203°C at night. The antennas and electronics would need to survive and function across these extremes.

Power delivery is another challenge. Traditional centralized power systems with cables are too heavy and inefficient. The team explored alternatives—fiber optics, free-space RF transmission, and foil-based antennas that can unfold or inflate once deployed. But each system must also minimize its own RFI emissions, or risk contaminating the very signals it’s trying to detect.

One particularly elegant solution is using ultralight foil antennas paired with temperature-tolerant amplifiers. This minimizes mass and allows for flexible deployment mechanisms, like robotic rovers or unrolling systems that place the antennas with high precision. The layout must be exact; even small errors in placement can distort the data, introducing noise and degrading the final cosmological maps.

From Lunar Telescopes to Earthly Applications

Even if DEX never launches, the technologies developed for it will ripple across industries. Brinkerink notes that the foil antenna technology, for instance, could revolutionize communications on small satellites or probes operating in hostile environments. Similarly, thermal-tolerant amplifiers could be used in desert or polar research stations, and precise antenna-deployment systems might inform next-gen military or commercial sensor arrays.

But if DEX does launch, it could become one of humanity’s most important astronomical instruments—not by taking beautiful images of galaxies, but by listening to the slow unfolding of structure in the early cosmos.

Its measurements could finally allow us to build a 3D map of the universe’s adolescence. We might see the first “clumps” of dark matter forming scaffolds for galaxies, or the gradual glow of hydrogen reionization as starlight dawned. We might even solve the riddle of how supermassive black holes formed so quickly, or what role exotic physics played in shaping the universe’s first billion years.

A Telescope in the Shadows

In the end, DEX represents not just a scientific instrument, but a philosophical one. It aims to explore a time when the universe was devoid of light and life, governed only by gravity and quantum fluctuations—before atoms knew how to shine.

It’s a telescope that will never see the Sun, or Earth, or even stars in a conventional sense. Instead, it will listen to a kind of cosmic heartbeat, nearly 14 billion years old, humming through time at wavelengths no human ear can detect.

As space agencies prepare for a renaissance of lunar exploration, the vision of telescopes like DEX challenges us to think beyond boots on regolith. It asks: What if the Moon is not our destination, but our vantage point? What if the far side of the Moon is not just a silent wasteland, but the perfect listening post for answering humanity’s oldest question: Where did we come from?

With the Dark Ages Explorer, we may finally hear the universe’s answer.

Reference: C. D. Brinkerink et al, The Dark Ages Explorer (DEX): a filled-aperture ultra-long wavelength radio interferometer on the lunar far side, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2504.03418