Each spring, as snow melts from the northernmost reaches of our planet, a symphony rises over the tundra. Loons trill from thawing lakes, geese honk their way across vast skies, and downy chicks tumble awkwardly from nests tucked into mossy hollows. The Arctic, for all its cold and darkness, becomes a nursery of extraordinary abundance.

And it’s been that way for a very, very long time—at least 73 million years, scientists now say.

According to a groundbreaking study published in Science, ancient birds were nesting in the high latitudes of what is today northern Alaska long before mammals took over the Earth. The discovery pushes back the earliest known evidence of avian reproduction in the polar regions by at least 25 million years. At a time when dinosaurs still ruled the planet, birds were already colonizing and raising their young in the long-light summers of the Arctic.

“It’s kind of mind-blowing,” says Lauren Wilson, lead author of the study and a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University, who conducted the work as part of her master’s degree at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “Birds have existed for around 150 million years, and this research shows that for half of that time, they’ve been nesting in the Arctic.”

Unearthing Ghosts from the Prince Creek Formation

The findings center on the Prince Creek Formation, a fossil-rich band of ancient sediment that runs along Alaska’s Colville River on the North Slope. This frigid and remote region is best known for yielding spectacular dinosaur fossils—duck-billed hadrosaurs, tyrannosaurs, and horned ceratopsians that roamed a very different Arctic during the Late Cretaceous.

But amid the famous giants of the Mesozoic, something much smaller and more delicate was hiding: the fossilized bones of baby birds.

“We found over 50 bird bones and bone fragments, many from hatchlings,” Wilson explains. “That in itself is astonishing. Baby bird bones are incredibly fragile—porous, thin, and prone to destruction. That we found so many is just remarkable.”

Indeed, the presence of such delicate material reveals not just the existence of birds, but something far more intimate: they were nesting there, not simply passing through. These ancient Arctic birds weren’t occasional migrants—they were residents, raising their young under the watchful gaze of polar summer skies.

Avian Diversity in a Dinosaur World

The fossil remains suggest a surprising diversity of species. Among the findings are bones from diving birds that resembled modern-day loons, as well as gull-like shorebirds and several types of waterfowl that bear a strong resemblance to today’s ducks and geese.

“The diversity is striking,” says Dr. Pat Druckenmiller, director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North and Wilson’s former advisor. “These weren’t just primitive flappers. Some of them may have been part of Neornithes, the lineage that includes all modern birds.”

If confirmed, that would make them the oldest known representatives of modern birds, predating previous fossil evidence by up to four million years. Some of the bones show hallmarks of this group: specific joint features, robust pectoral structures, and perhaps most intriguingly, a lack of true teeth—a trait seen in today’s beaked birds.

“We can’t say for certain yet,” Druckenmiller cautions. “We’d need a partial or full skeleton to nail that down. But if they are Neornithes, they’d be the oldest on record, period.”

Rewriting Polar Paleohistory

Prior to this study, the oldest known record of birds breeding at the poles came from 47 million years ago, long after the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event wiped out most life on Earth—including the non-avian dinosaurs. That previous evidence came from fossil finds in Antarctica and other temperate polar zones.

Wilson’s findings now shift that reproductive timeline back into the Late Cretaceous, when Earth’s continents were still rearranging themselves and much of the planet was blanketed in warm greenhouse conditions. Yet the Arctic, even then, was a challenging place to live.

Despite higher global temperatures, this ancient polar landscape endured months of winter darkness, occasional frosts, and seasonal food scarcity. For a long time, paleontologists assumed such conditions were too extreme for delicate nesting birds.

“Clearly, that assumption was wrong,” Wilson says. “These birds were hardy. They weren’t just surviving—they were thriving.”

Tiny Bones, Big Revelations

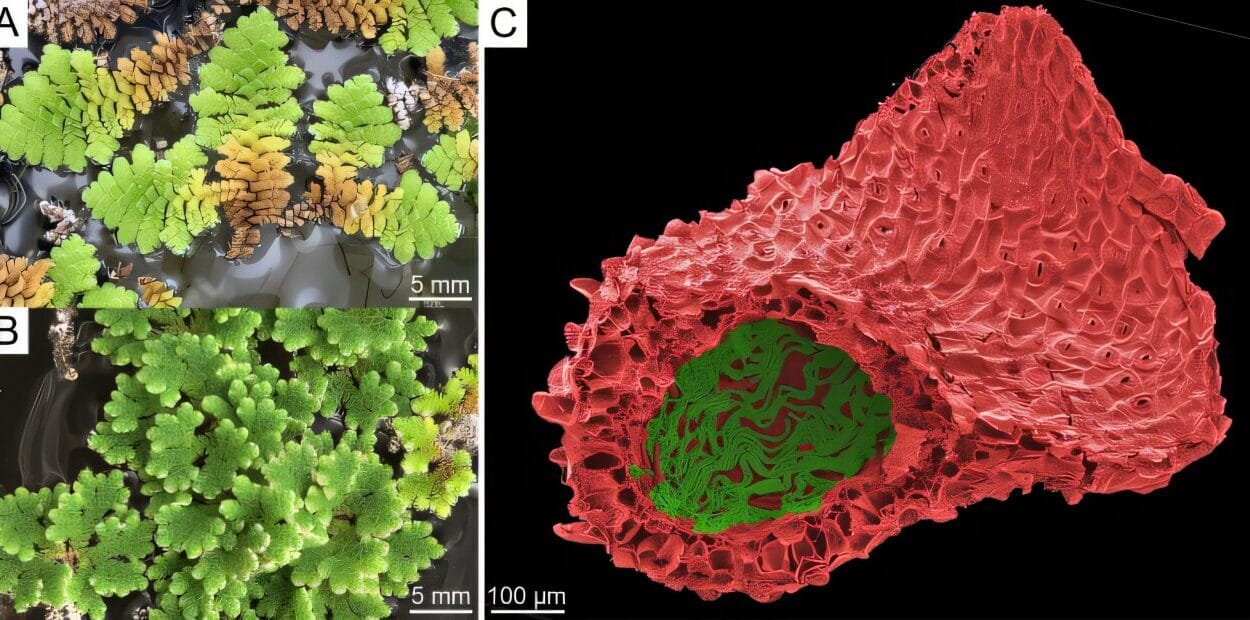

The key to this discovery lies in a unique excavation strategy. Most vertebrate paleontology focuses on finding big bones—skulls, femurs, teeth from large animals that are easier to spot and extract. But at the Prince Creek Formation, scientists use a meticulous, sediment-sifting method that opens a window into the tiniest corners of prehistory.

Buckets of soil are collected and screen-washed, then painstakingly examined under microscopes. What emerges are microfossils—millimeter-sized fragments of bone, teeth, and shell that often go unseen at other sites.

“It’s not glamorous work,” Druckenmiller says with a laugh. “But it yields extraordinary results. We’ve found fossils of tiny mammals, baby dinosaurs, and now, hatchling birds. That approach has made Alaska one of the top sites in the world for Cretaceous bird fossils.”

And those little bones, while humble, are information goldmines.

Each bone fragment tells a story about growth rates, physiology, and behavior. They can reveal whether the young birds were precocial (able to feed and move soon after hatching) or altricial (helpless and requiring intensive care). The size, shape, and mineral density of the bones also hint at how long the chicks may have remained in the nest—and therefore, how long their parents stayed in the Arctic.

“That has implications for migration theories,” Wilson notes. “If these birds were nesting and staying long enough to raise chicks, it challenges the idea that early birds were simply seasonal visitors to high latitudes. They were permanent residents.”

An Evolutionary Nursery

The implications extend beyond bird evolution. The Arctic of the Cretaceous may have functioned as a kind of evolutionary crucible, selecting for traits like cold tolerance, long daylight adaptation, and even avian intelligence.

“It’s fascinating to think that today’s migratory geese and ducks, which breed in the Arctic, might be carrying on a tradition millions of years old,” Druckenmiller says. “It’s continuity on a scale that’s hard to comprehend.”

Indeed, Alaska’s modern wetlands, teeming with spring hatchlings, echo a scene that unfolded long before humans, mammoths, or even grass. The Arctic may very well be the cradle of modern bird behavior—a place where early avians honed the strategies that would help them outlast extinction and spread across every continent on Earth.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, a few tiny bones might seem like a small scientific footnote. But this find is a profound reminder of how much the polar regions still have to teach us. They are repositories of deep time, preserving not just fossils but patterns—of life, climate, resilience, and survival.

As modern-day Arctic ecosystems face unprecedented change, from climate disruption to habitat loss, this kind of research becomes even more poignant. It provides a long-view perspective, reminding us that these fragile habitats have nurtured life through multiple mass extinctions, tectonic upheavals, and climatic extremes.

But while ancient birds may have weathered an asteroid, today’s birds face threats of an entirely different kind—ones caused not by space rocks, but by human activity. The survival of modern avian species may depend on what we choose to do in the next few decades.

The Next Steps in the Fossil Record

For Wilson and her colleagues, this discovery is just the beginning. They plan to continue excavations at the Prince Creek Formation and hope to find more complete specimens—perhaps even an intact Arctic bird skeleton.

“We’re starting to see a bigger picture of life in the Cretaceous Arctic,” Wilson says. “It wasn’t just a fringe ecosystem—it was a thriving community of dinosaurs, mammals, fish, and birds. Every bone we find adds a new piece to the puzzle.”

In the meantime, the tiny bones collected in Alaska now reside in the collections of the University of Alaska Museum of the North—a treasure trove of ancient life, tucked away just miles from where modern birds still gather in vast numbers to rear their young.

Back at Creamer’s Field, a migratory stopover near Fairbanks, the echoes of deep time can almost be heard. Geese honk, ducklings paddle across thawed ponds, and the air is filled with the same instinctive rhythm that once guided hatchlings through a polar Cretaceous dawn.

They’ve been doing this for 73 million years.

Reference: Lauren N. Wilson et al, Arctic bird nesting traces back to the Cretaceous, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adt5189. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt5189