Eighty million years ago, in what is now the Brazilian state of São Paulo, herds of massive sauropods roamed a harsh and arid landscape. These gentle giants, with their sweeping necks and pillar-like legs, were among the largest animals ever to walk the Earth. Yet even these titans were not invincible. A new study reveals a haunting truth: some of them carried within their bones the signs of a painful and ultimately fatal disease.

In the municipality of Ibirá, paleontologists uncovered fossilized bones bearing unmistakable traces of osteomyelitis, a destructive infection of the bone that, even today, can devastate humans and animals alike. These findings, published in The Anatomical Record, shed new light on the vulnerabilities of dinosaurs and the deadly environments they lived in.

Unearthing Clues from Stone

The fossils came from six individual sauropods, discovered between 2006 and 2023 at a site evocatively named Vaca Morta, or “Dead Cow.” Though the bones had turned to stone, they still carried within them the scars of disease. Using high-powered scanning electron microscopes and stereomicroscopes, researchers observed lesions that betrayed the silent struggle these animals endured.

Some bones bore spongy textures that indicated active infection spreading from the marrow outward. Others showed raised protrusions, strange bumps, or elliptical grooves etched into the surface, almost like fingerprints pressed into stone. These were no random imperfections; they were the physical echoes of an ancient illness.

What was most striking was what the bones lacked: signs of healing. Normally, fossils of injured dinosaurs—such as those bitten by predators—show evidence of regeneration, where new bone grows to repair damage. But here, the disease had left its victims no chance. The infection raged unchecked, and the dinosaurs died with it still consuming them.

A Landscape Ripe for Pathogens

Why did this disease appear in multiple animals, all in the same place and time? The answer lies in the environment of the São José do Rio Preto Formation, the ancient ecosystem where these creatures lived and died.

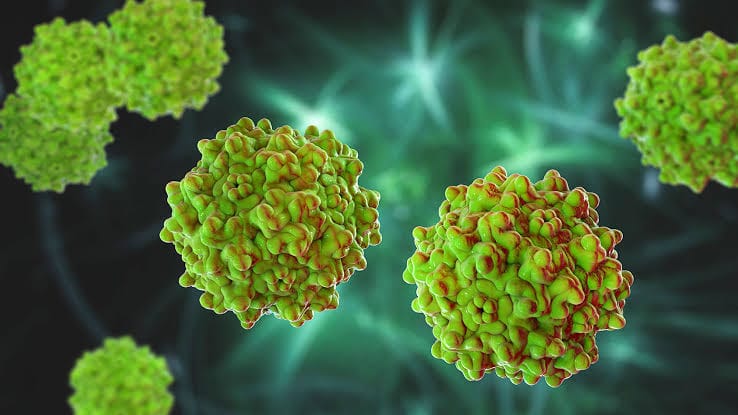

During the Late Cretaceous, this region was dry and arid, interrupted by shallow rivers and stagnant pools. These waters could trap unwary dinosaurs in mud, but they also harbored danger of another kind: pathogens. Bacteria, parasites, or fungi could thrive in such conditions, spreading through contaminated water or even insects like prehistoric mosquitoes.

Tito Aureliano, the study’s lead author, explains that the clustering of diseased fossils suggests the environment itself fostered outbreaks. Much like malaria and cholera thrive in specific modern climates, osteomyelitis may have found fertile ground in Cretaceous São Paulo. For the sauropods, the very water they needed to survive may have been the source of their undoing.

The Hidden Agony of Giants

When we imagine dinosaurs, we often picture them in dramatic battles: predators clashing with prey, titans fighting for dominance. Yet the story of these fossils reveals a quieter, more tragic truth. These sauropods may have endured prolonged pain—bones swelling, pus-filled lesions breaking through to skin and muscle—before succumbing to infection.

One of the most chilling discoveries was that the lesions could have connected to soft tissues, leaving open wounds that oozed blood or pus. It paints a picture not of invulnerable giants, but of living beings that could suffer as deeply as modern animals.

The discovery also challenges us to see dinosaurs not as distant monsters, but as creatures bound to the same biological struggles we face today. Diseases that ravage humans—whether bacterial, viral, or parasitic—also plagued them. In their bones, we glimpse a shared vulnerability across time.

Science in the Service of Empathy

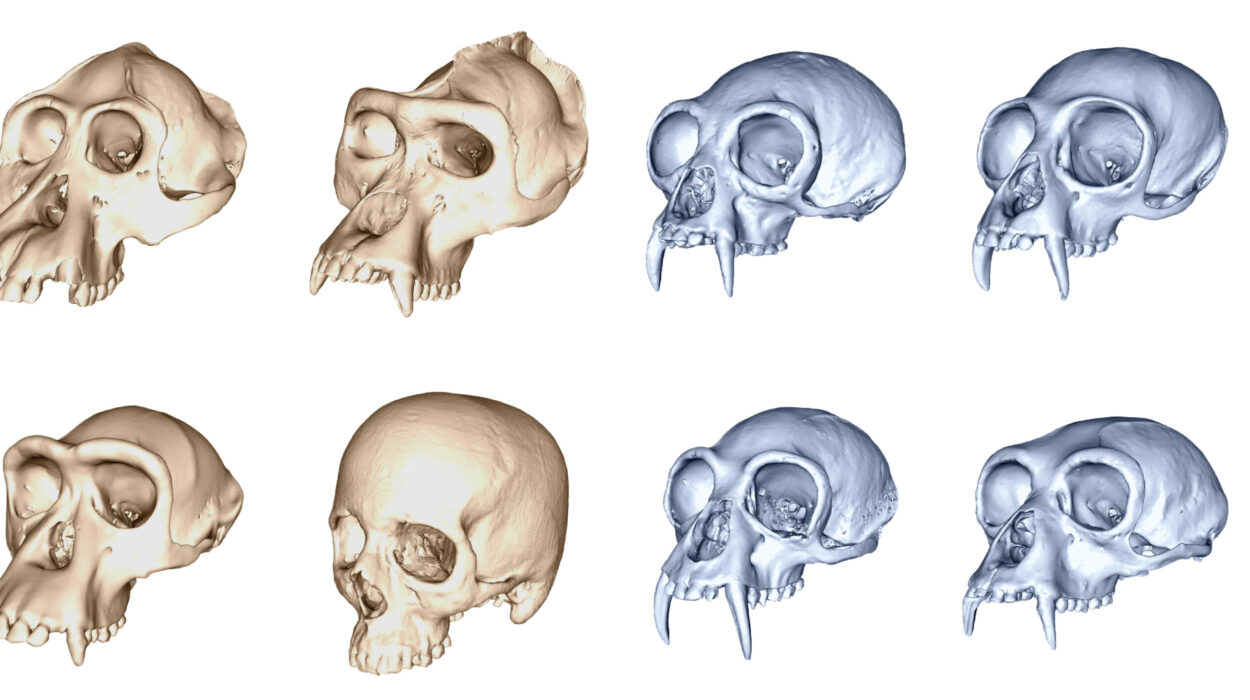

This study does more than catalog strange fossil patterns; it teaches paleontologists how to distinguish between different bone pathologies. By identifying three distinct manifestations of osteomyelitis, the researchers provide tools for future discoveries. They showed how infections can mimic cancers like osteosarcoma, but with subtle differences that careful observation can reveal.

But beyond the scientific precision lies a deeper human lesson. When we peer into these bones, we do not just study anatomy; we enter into the lived experience of animals long extinct. We learn that they were not only massive and powerful but also fragile in ways that resonate with our own struggles against disease.

A Bridge Between Eras

In 2021, another study from the same site described osteomyelitis in Ibirania parva, a smaller sauropod species. That case was linked to parasites attacking the blood. Together with the new findings, these discoveries suggest that prehistoric disease was not rare or incidental but perhaps a recurring feature of dinosaur life in this environment.

The Vaca Morta site, with its treasure trove of fossils, thus tells not just of extinction but of existence—of daily battles for survival in a world filled with unseen enemies. Dinosaurs, turtles, and crocodile-like creatures all shared this landscape, and all may have faced the invisible hazards of infection.

The Legacy of Ancient Illness

What does it mean for us, today, to know that dinosaurs fell victim to the same kinds of infections that still challenge modern medicine? Perhaps it reminds us of the continuity of life, of how pathogens have shaped evolution across eons. It also underscores the fragility of even the mightiest species when confronted with microorganisms too small to see.

The fossils of Ibirá do more than reveal disease; they reveal connection. They show us that, despite their size and majesty, dinosaurs were mortal in the same ways we are. They lived, they suffered, and they died, leaving behind silent records carved into their bones.

And in studying those records, we learn not only about them but about ourselves—the universality of vulnerability, the endurance of life, and the timeless struggle against the unseen forces that shape existence.

More information: Tito Aureliano et al, Several occurrences of osteomyelitis in dinosaurs from a site in the Bauru Group, Cretaceous of Southeast Brazil, The Anatomical Record (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ar.70003