More than half a billion years ago, long before dinosaurs walked the Earth or forests shaded its surface, the seas teemed with strange and unfamiliar creatures. These were the Cambrian oceans—a time when evolution was experimenting wildly, producing body plans that would shape life for the next 500 million years. Among these bizarre animals was a tiny segmented creature no bigger than a thumbnail, yet its legacy would ripple across deep time.

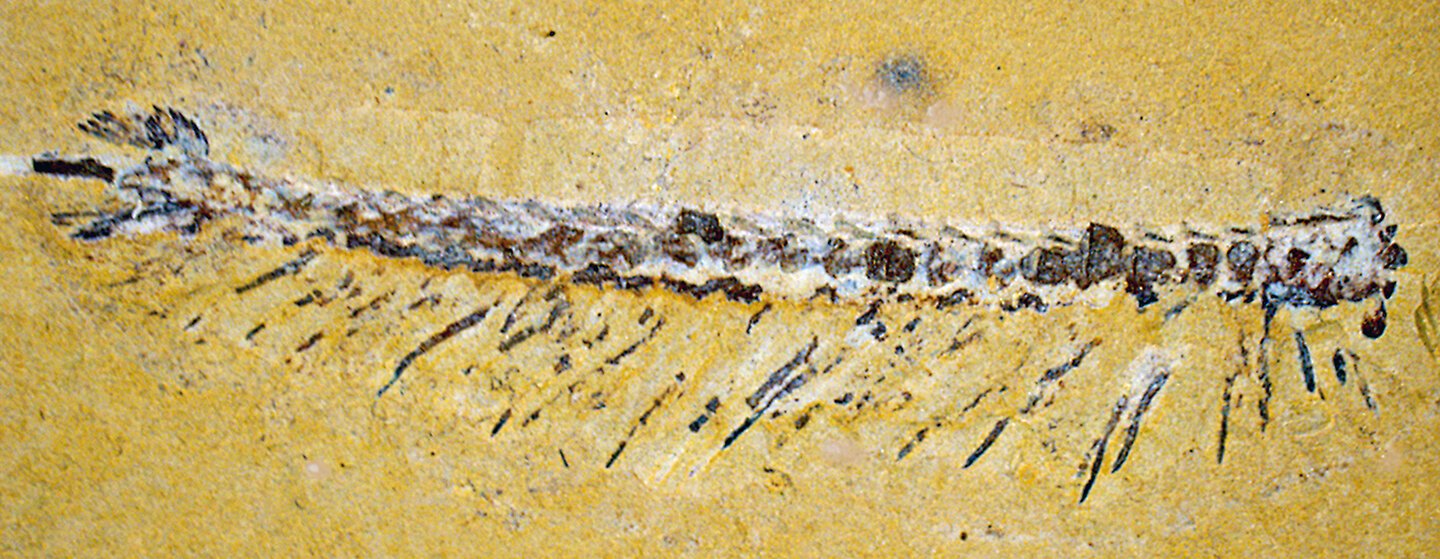

That creature is Jianfengia multisegmentalis, a long-extinct arthropod whose delicate fossil has become the key to solving one of evolutionary biology’s most enduring puzzles. A new study published in Nature Communications has revealed that this fossilized animal, with its peculiar appendages and surprisingly modern brain, has helped scientists redraw the arthropod family tree. What it reveals is nothing short of astonishing: the evolutionary split that gave rise to insects, crabs, millipedes, spiders, and scorpions may be written in the neural blueprint of this tiny ancient animal.

Why Arthropods Matter

To appreciate the importance of this discovery, we need to understand just how successful arthropods are. Arthropods—meaning “jointed feet”—are the most diverse and abundant group of animals on Earth. They include insects, crustaceans, spiders, scorpions, millipedes, and countless others. More than 80% of all known animal species belong to this single group. They fly, crawl, swim, dig, and climb. They are pollinators, predators, parasites, and prey. Without them, ecosystems as we know them would collapse.

And yet, despite their dominance, the earliest chapters of their story have remained hazy. In particular, scientists have long struggled to understand when and how arthropods split into their two largest evolutionary branches: mandibulates—those with jaws, like insects and crustaceans—and chelicerates—those with fang-like mouthparts, like spiders and scorpions.

Jianfengia, preserved in stone for over 525 million years, has finally given us a clearer view.

The Enigma of the “Great Appendages”

When Jianfengia was first discovered in 1984 by paleontologist Xianguang Hou in Yunnan, China, it seemed to belong to a group of ancient creatures called megacheirans, meaning “large hands” in Greek. These animals were so named because of their striking “great appendages”—sturdy, claw-like limbs extending from their heads, perfect for grasping prey.

For decades, scientists assumed these appendages were the evolutionary forerunners of the fangs and pincers we see today in chelicerates. After all, they looked like the formidable grasping claws of the horseshoe crab, a living chelicerate considered a “living fossil.” This interpretation placed Jianfengia firmly in the chelicerate branch of the arthropod family tree.

But appearances can be deceiving.

Looking Into an Ancient Brain

The breakthrough came not from bones or shells, but from something far more delicate—the brain. Fossilized brains are incredibly rare because soft tissues decay quickly. Yet in the fine-grained rocks of Yunnan, the imprint of Jianfengia’s nervous system was preserved with stunning clarity.

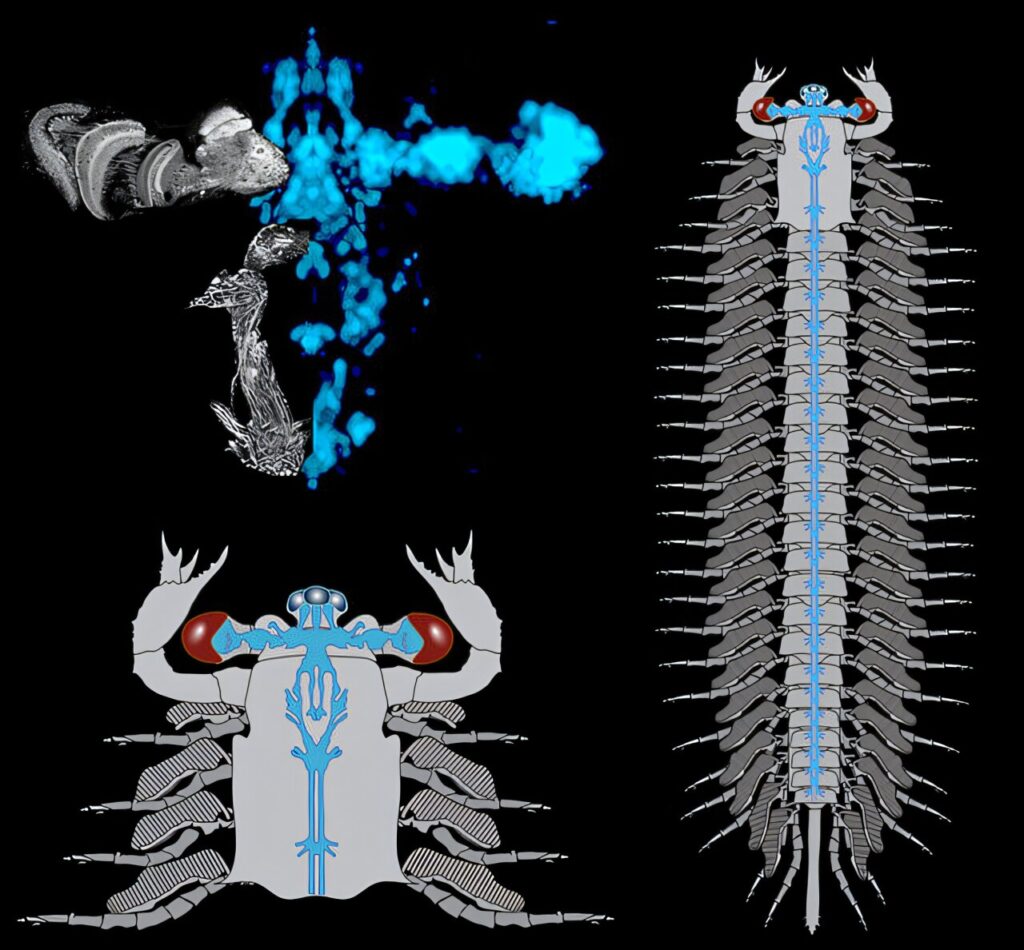

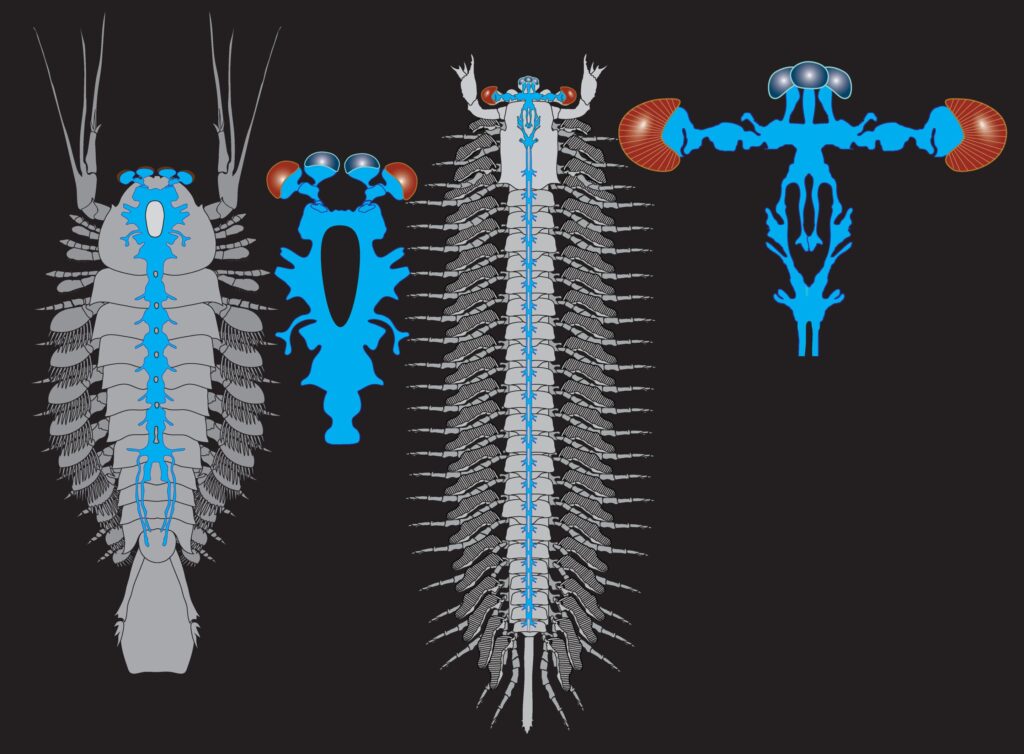

Nicholas Strausfeld, a neuroscientist at the University of Arizona, and his team examined four Jianfengia fossils, enhancing subtle contrasts in the rock until the neural structures emerged. What they saw stunned them. Jianfengia’s brain was not arranged like that of a horseshoe crab or spider, but like that of a shrimp or crayfish. Its neural architecture—how its brain segments connected to its eyes and appendages—was unmistakably aligned with mandibulates, not chelicerates.

In other words, Jianfengia had been misclassified for decades. Its great appendages, once thought to be the ancestors of spider fangs, were actually precursors of the antennae-like structures seen in insects and crustaceans today.

A Tale of Two Fossils

The story deepens when Jianfengia is compared with another megacheiran: Alalcomenaeus. This fossil, also exquisitely preserved, had a brain more consistent with chelicerates, resembling the organization seen in modern-day horseshoe crabs.

Here lies the breakthrough: two fossils, both once lumped together in the same group, actually represent the roots of the two great arthropod lineages. Jianfengia belongs to the ancestors of insects, crabs, and millipedes; Alalcomenaeus belongs to the ancestors of spiders and scorpions. What once seemed a single evolutionary branch has now been revealed as a fork in the great arthropod family tree.

Why Brains Matter More Than Bones

This discovery highlights a crucial point in paleontology: sometimes the answers aren’t in the skeleton, but in the nervous system. Exoskeletons can mislead, as structures may look similar yet evolve for different purposes. Brains, however, preserve the organization of life at a deeper level, reflecting developmental patterns that trace back to ancient genetic programs.

Strausfeld explained it best: “Our results demonstrate that close examination of fossilized neural remains can provide powerful data indicating evolutionary relationships impossible to obtain just from features of the exoskeleton.”

In Jianfengia’s case, its compound eyes, simple eyes, and neural wiring revealed a sophisticated arrangement that connected it directly to modern mandibulates. Even the tiny “cone cells” that supported its photoreceptors were fossilized, offering a breathtaking window into the vision of a creature that lived over 500 million years ago.

A Living Echo of the Past

One of the most remarkable aspects of this study is how the past still resonates in the present. Strausfeld pointed to modern ostracods—tiny crustaceans that still carry antennules tipped with claspers, eerily echoing the great appendages of Jianfengia. Evolution, it seems, rarely discards its old tools completely. Instead, it reshapes them, repurposes them, and threads ancient features into new forms.

The great appendages of Jianfengia became antennules. The great appendages of Alalcomenaeus became spider fangs. From a single body plan came two wildly different evolutionary solutions. This is the creativity of evolution at work.

The Cambrian Explosion Revisited

The discovery also casts new light on the Cambrian Explosion, the evolutionary burst around 540 million years ago when most major animal groups first appeared. The fossils from Yunnan’s Burgess Shale–like deposits have long fascinated scientists because they capture this extraordinary period of innovation.

Jianfengia reminds us that this was not just a time of new body plans, but of new brains. Nervous systems were diversifying, laying the groundwork for the sensory and behavioral complexity that would allow arthropods to dominate nearly every habitat on Earth.

The robustness of these ancient neural designs may explain why arthropods have been so astonishingly successful. Their genetic and developmental architecture proved both stable and versatile—able to produce spiders weaving webs, bees navigating with sunlight, crabs scuttling sideways, and dragonflies with aerial mastery.

Why This Tiny Fossil Matters to Us

It might be tempting to dismiss Jianfengia as just another obscure fossil, relevant only to specialists. But its story resonates far beyond paleontology. It tells us something profound about how life evolves: that enormous diversity can spring from tiny differences, that the history of life is written in structures as delicate as neurons, and that sometimes the greatest evolutionary revolutions happen in the smallest of creatures.

More than that, it connects us to deep time. Every insect buzzing in summer air, every spider spinning its web, every crab burrowing in the sand carries echoes of Jianfengia’s tiny brain. We are surrounded by the legacy of this half-billion-year-old animal, whether we notice it or not.

Science thrives on moments like this—moments when a small discovery reshapes our understanding of the grand story of life. Jianfengia may have been small, but its impact is enormous.

A New Chapter in the Story of Life

The fossil of Jianfengia multisegmentalis reminds us that the history of life is not a fixed tale, but an unfolding narrative. Each new fossil, each new discovery, adds a twist to the plot. Sometimes the heroes are not towering dinosaurs or monstrous sea reptiles, but creatures so small you could miss them with a blink.

What makes this story emotionally powerful is not just that it rewrites the past, but that it reminds us of the fragility and resilience of life. Against all odds, a two-millimeter-wide head and its ancient brain were preserved for over half a billion years, waiting for us to uncover its secret. In doing so, it gave us not only a clearer view of arthropod evolution but also a deeper sense of wonder for the hidden threads that bind all life together.

The next time you see a spider weaving its web, or a dragonfly hovering by a pond, remember: their story began in a shallow sea half a billion years ago, with a tiny creature whose fossil brain still speaks across the ages.

More information: Brain anatomy of the Cambrian fossil Jianfengia multisegmentalis informs euarthropod phylogeny, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-62849-w