For centuries, a fascinating and little-known relationship has flourished in the forests and woodlands of sub-Saharan Africa. It’s a rare example of cooperative behavior between humans and a wild animal—the greater honeyguide (Indicator indicator), a small, brownish bird that seems to defy the usual boundaries of interspecies communication. These birds are famous for leading human honey hunters to beehives, not out of kindness or domestication, but for a very specific reason: they want the wax. Once humans break open the hive and collect the sweet honey inside, they often leave behind the waxy comb, which the honeyguides eagerly consume. It’s a mutualistic exchange honed over generations—one that, until recently, seemed straightforward and beneficial to both parties.

But a new study out of Mozambique has stirred the pot. Could these birds, revered and respected by local communities, be capable of revenge?

The Whispered Tales of Betrayal

Local lore among honey-hunting communities in Mozambique and beyond suggests that not all honeyguides play fair—or perhaps more intriguingly, that they demand fairness from their human counterparts. For generations, stories have circulated of honeyguides leading greedy or careless hunters not to honey-laden hives, but to peril instead: venomous snakes curled under logs, snarling beasts lurking in the shadows, or dry, lifeless places devoid of bees altogether.

To some, these stories are dismissed as colorful folklore, embellished through oral tradition. But to the hunters who rely on the birds, they are warnings with weight: never cheat a honeyguide. Never take without giving. And never underestimate the bird’s memory.

Following the Birds, One Hunt at a Time

In an attempt to probe this extraordinary possibility, three researchers—David Lloyd-Jones, Musaji Muamedi, and Claire Spottiswoode—undertook a scientific expedition to track the honeyguides’ behavior in Mozambique. Their mission was as delicate as it was ambitious: to find out whether honeyguides really do lead humans to danger when slighted in the past—or whether something else entirely explains these misdirections.

Published in Ecology and Evolution, their study took a careful, observational approach. The researchers joined local honey-hunters in Niassa National Reserve, a remote and biodiverse area teeming with both bees and predators. By embedding themselves in these expeditions, they hoped to witness, firsthand, how the birds behaved in different contexts—especially after previous hunts in which rewards were given or not.

Into the Wild: Unexpected Encounters

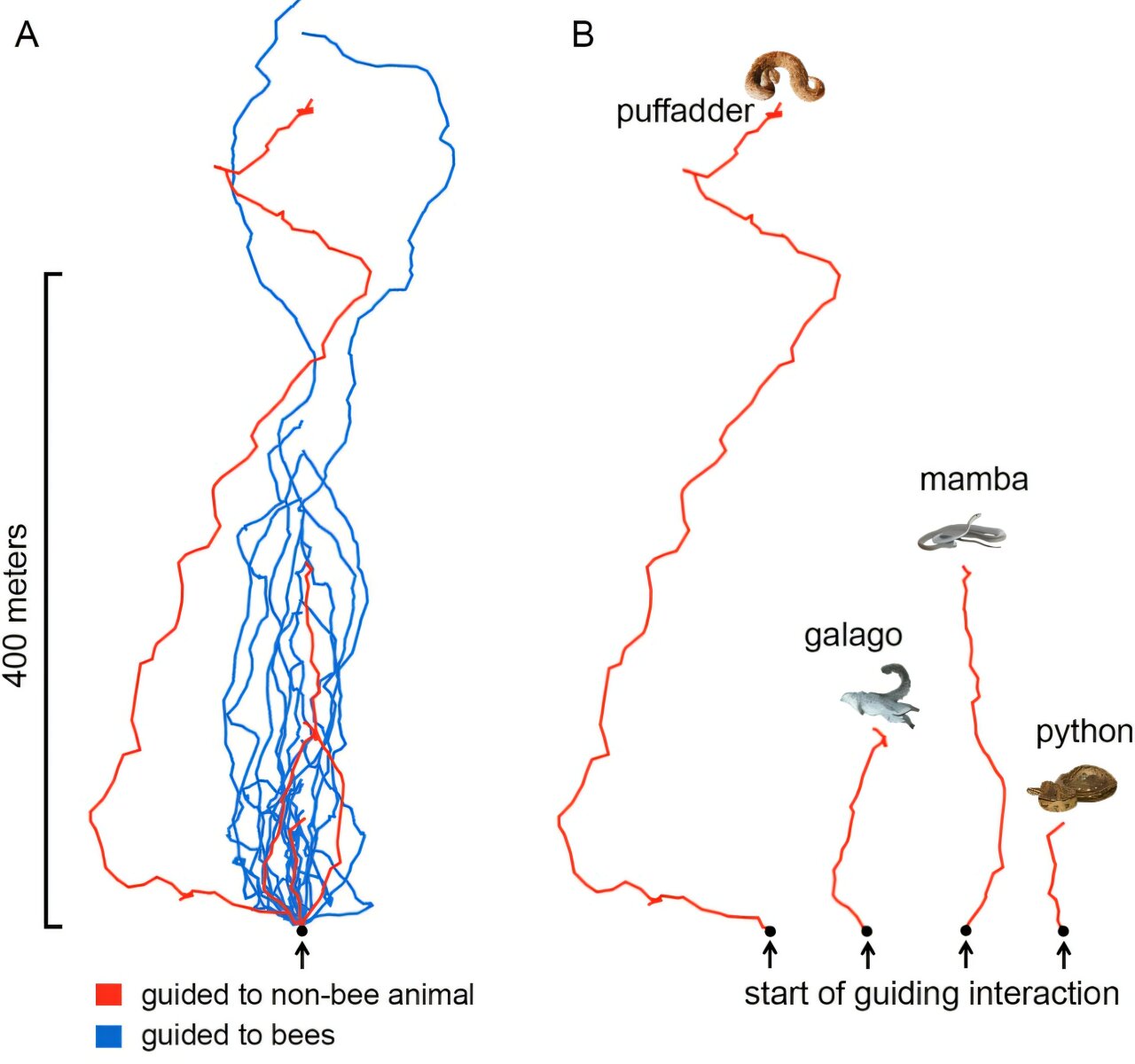

Over the course of their fieldwork, the researchers followed the calls and flight patterns of honeyguides multiple times. Most hunts went as expected: the birds performed their telltale chatter, darted through the trees, and guided the group to beehives nestled in hidden tree cavities or high in the canopy.

But on four separate occasions, things took a strange turn.

Three times, the birds led the hunters not to bees but to venomous snakes—each out in the open and clearly visible. A fourth mislead involved a dead galago, or bush baby, a small primate of nocturnal habits. In all four instances, the honeyguides exhibited the same behavior they used when guiding people to beehives: specific calls, flight maneuvers, and swooping down at precise locations to signal a find.

To any observer, it appeared that the birds were deliberately identifying these non-honey targets as though they were of equal value to a beehive. Was this retribution? A practical joke? Or a bird’s version of a stern warning?

Analyzing the Bird’s Intent

Faced with these eerie misdirections, the researchers did not jump to conclusions. While the deliberate-seeming behavior was intriguing, Lloyd-Jones and his colleagues doubted that honeyguides had the cognitive machinery necessary for human-like vengeance. Could a bird really remember a specific human’s failure to leave behind wax? And even if it could, would it plot to lead that person to danger as a form of punishment?

The answer, at least from a scientific standpoint, seems unlikely. Birds—even intelligent ones like corvids and parrots—have demonstrated memory, problem-solving, and even tool use. But the notion of planning a future punishment for a past slight edges into cognitive territories like theory of mind and revenge—traits that even many mammals struggle to demonstrate clearly.

Instead, the researchers proposed a more grounded explanation: spatial recall errors.

A Bird’s Eye View of the Forest

Honeyguides use a variety of cues to find beehives: scent, memory, and possibly even other animals’ behavior. Over time, they develop a spatial map of their territory. The researchers suggest that when a honeyguide leads humans to a snake or a dead animal, it might be recalling a location where food—or what it once thought was food—was found in the past.

In this light, the misdirections might not be acts of punishment but rather honest mistakes. A bush where bees once swarmed could now host a snake. Or perhaps the glint of galago fur once mirrored wax in the bird’s perception. The honeyguide, then, is still trying to help—or at least trying to replicate behavior that previously led to a reward.

And yet, the deliberate signaling—the calls, the guidance, the swoops—cannot be ignored. Why, the researchers ask, would the bird go through the same motions for such irrelevant or even dangerous targets?

This opens up a tantalizing possibility: perhaps the bird wasn’t trying to retrieve wax, but rather warning the humans about the presence of danger. The snakes, after all, were out in the open. Could the honeyguide be expanding its cooperative repertoire—protecting its human partners as well as leading them to food?

Revenge or Alliance?

Here lies the real puzzle: how much of this behavior is rooted in selfish instinct, and how much in social awareness?

From an evolutionary perspective, the honeyguide’s cooperation with humans is rare and advantageous. It’s one of the only known examples of a non-domesticated, wild animal forming a repeated cooperative relationship with humans. The behavior is so ingrained that both birds and people in regions like Mozambique have developed shared communication—humans use a specialized call known as a “brrrr-hmm” to attract the birds, who then respond with their own guiding calls.

Given this rich interspecies dialogue, it’s not unreasonable to suspect that honeyguides are more socially attuned than previously thought. Whether they’re calculating revenge or simply reacting to remembered hotspots is still up for debate. But either way, their actions suggest a complex navigation of their environment and their human collaborators.

Human Interpretations and Cultural Memory

To the local honey-hunters, there’s little question: these birds know what they’re doing. Generations of experience have taught communities to respect the honeyguide not just as a helper, but as a being with agency, emotion, and memory. The tales of vengeful birds might not hold up to scientific scrutiny in terms of cognition, but they do reflect a deep understanding of animal behavior built through lived interaction over centuries.

These stories—woven into the cultural fabric of Mozambique and other parts of Africa—are a testament to human observation and respect for the natural world. And they offer something that science alone sometimes misses: the acknowledgment that animals are not just background noise in human lives, but active participants.

The Future of Honeyguide Research

The findings from Lloyd-Jones, Muamedi, and Spottiswoode don’t close the case on honeyguides—they open it wider. Could individual birds remember specific humans? Could their behavior vary based on prior treatment? How do they learn which spots lead to rewards, and how do they decide what to signal?

Further research, combining field observations with experiments in avian cognition, might help answer these questions. Tracking specific birds over time, using technology to map their memory patterns, or studying the neurological processes involved in their behavior could offer clues.

But no matter what future studies reveal, one thing is clear: the honeyguide-human relationship is one of nature’s most remarkable partnerships—built not on domestication, but on mutual benefit, trust, and communication.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Bird

In a world where the line between myth and science often feels blurred, the story of the honeyguide stands as a perfect blend of both. Whether leading humans to honey, misguiding them to danger, or simply trying to help in its own mysterious way, the honeyguide reminds us that intelligence in nature takes many forms.

Perhaps the bird is not vengeful—but that doesn’t mean it’s simple. In the tangled ecosystems of Mozambique, among whispering trees and hidden hives, a little brown bird carries the weight of centuries of tradition, curiosity, and wonder. And in every call it utters and every swoop it makes, it invites us to look closer—not just at the forest, but at the minds within it.

Reference: David J. Lloyd‐Jones et al, To Bees or Not to Bees: Greater Honeyguides Sometimes Guide Humans to Animals Other Than Bees, but Likely Not as Punishment, Ecology and Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ece3.71136