In the quiet ruins of Naachtun, an ancient Mayan city nestled in the heart of modern-day Guatemala, a hidden piece of history was waiting to be uncovered. As archaeologists carefully sifted through the layers of earth and stone, they unearthed something unexpected: a mosaic gameboard, embedded directly into the floor of a structure. It wasn’t just any gameboard, but a Patolli—a high-stakes Mesoamerican game of strategy and chance that was once at the center of cultural life across the ancient Maya world.

This discovery is more than a simple artifact. It’s a glimpse into a world where games weren’t just pastimes, but integral to the social fabric, the architecture, and even the spiritual practices of a civilization.

A Game of Strategy and Luck

Patolli was no ordinary game. It was a game of chance and strategy, often played with stakes that could include crops, wealth, or other valuable goods. For the Maya, the Patolli board was more than just a way to pass the time. It was a game with deep cultural significance, woven into the daily rhythms of their lives.

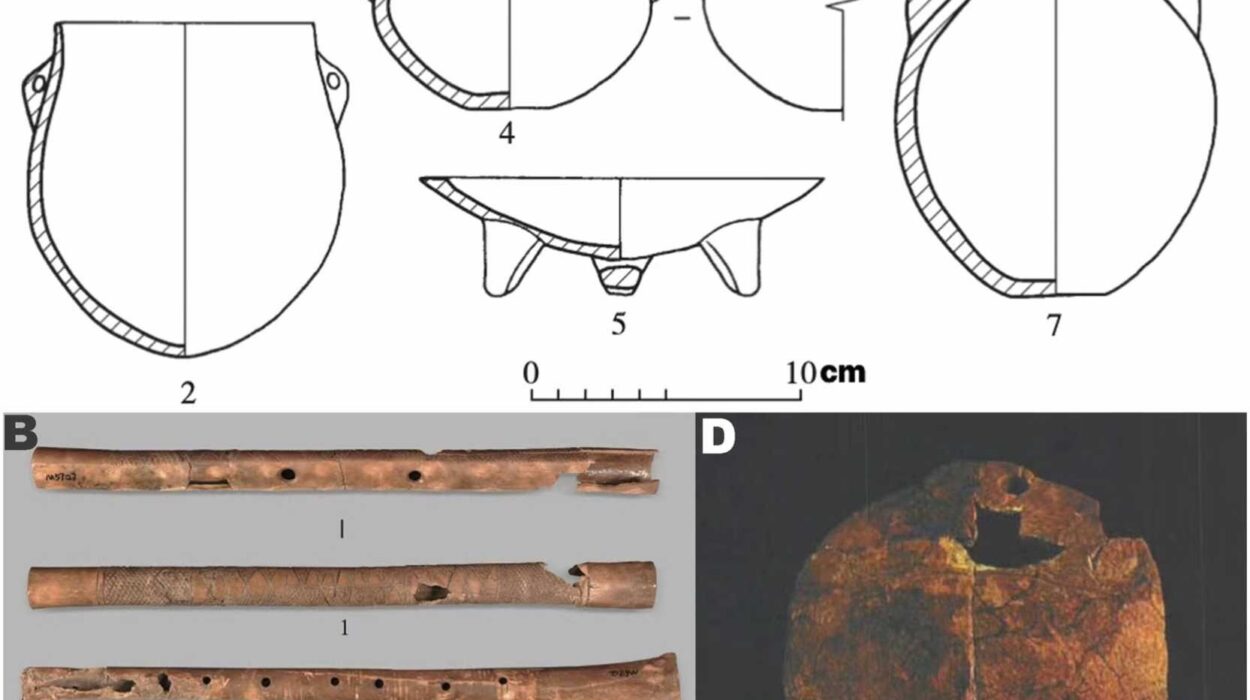

The game itself was often played on a cross-shaped board, and its rules were intricate, challenging players to roll beans or stones and race to the finish. Patolli wasn’t just about skill or luck—it was also about the spirit of competition and the potential for great social and political significance. The stakes were high, and the consequences of winning or losing could ripple through the community.

While Patolli was played across Mesoamerica, it took on unique forms in different cultures, with the Aztecs, Toltecs, and Maya each adopting their version of the game. Historical records and codices mention Patolli frequently, underscoring its importance in the region’s rituals, entertainment, and community-building.

The Surprising Discovery at Naachtun

The discovery at Naachtun is remarkable for a few reasons. While Patolli boards have been found at various archaeological sites across the Maya region, they were typically etched or painted onto walls, benches, or other existing surfaces. These carvings, though fascinating, often leave archaeologists guessing about their context. Were they created by the original inhabitants? Or were they added by later generations who lived in or around the same structures?

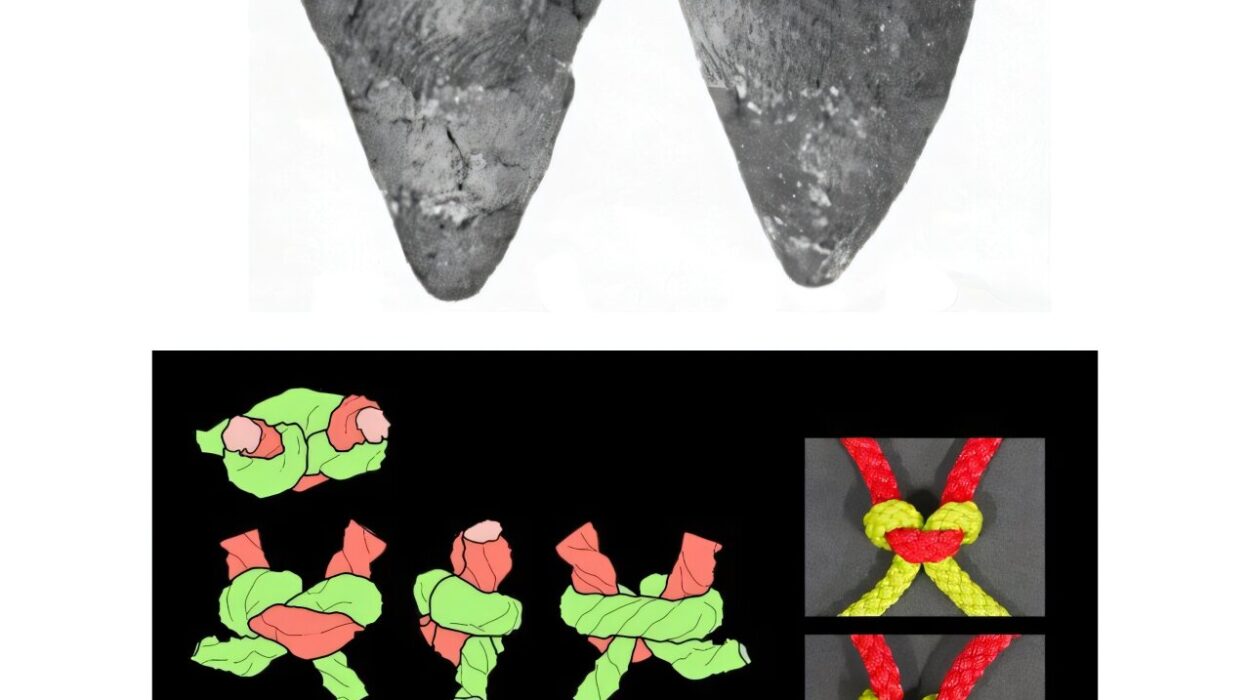

What sets this discovery apart is the fact that the gameboard was not an afterthought or a decorative addition. Instead, it was deliberately incorporated into the construction of the building itself. The mosaic Patolli gameboard, made up of hundreds of small ceramic pieces, was embedded in the mortar of the floor from the beginning—an integral part of the structure, not an afterthought.

“The fact that the gameboard was part of the original design of the building shows just how important this game was,” said one of the researchers involved in the excavation. “It wasn’t merely something people did in their spare time; it was woven into the fabric of their daily lives.”

The board, constructed from around 478 ceramic pieces in shades of red and orange, was unusually large compared to other Patolli boards found in the region. The researchers estimated its original size to be about 80 by 110 centimeters, significantly larger than the usual 40 to 70 cm dimensions typically seen in similar games. This added scale makes the find even more intriguing, suggesting that the game was not just for casual play but perhaps held more symbolic or ceremonial value.

The Historical and Cultural Context of the Find

Dating the gameboard was another challenge that helped reveal its historical context. While many etched boards have left researchers unsure of their exact origins or timing, the embedded mosaic offered a clearer picture. The researchers determined that the gameboard dated to the Early Classic period of the Maya civilization, around the fifth century AD.

This timeline is significant because it places the gameboard within a period of flourishing culture and architecture in the Maya world. The building where it was found was likely part of an elite family’s home or possibly a small administrative hub. The structure itself, along with the embedded gameboard, offers new insight into the role of Patolli in Maya society, not only as entertainment but as a marker of social status and community connection.

In the grand scheme of Mesoamerican history, Patolli was much more than a game. Archaeologists suggest that the practice of playing such games in palaces, temples, and elite residences was often linked to ceremonial events, spiritual beliefs, and the strengthening of political and social ties. By embedding the Patolli board directly into the architecture, the people of Naachtun were not merely playing a game—they were reinforcing the importance of these traditions as part of their culture’s daily rituals and communal identity.

The Maya’s Unique Relationship with Games

What makes this discovery even more fascinating is the way it sheds light on the Maya’s unique relationship with games. For them, games were not simply forms of entertainment or leisure activities. They were embedded in the social, political, and spiritual life of the community. Patolli, specifically, was often seen as a way to express power and influence, with elite players using their victories as a way to demonstrate their strategic thinking, as well as their luck and divine favor.

In a world where life and death, wealth and poverty, and power and weakness were all bound up in the chance outcomes of a game, Patolli could have very real consequences. Archaeological evidence from other Maya sites shows that Patolli boards were frequently found in spaces of authority—palaces, temples, and civic centers. The game was not just for fun; it was deeply woven into the ceremonial fabric of Maya society.

Why This Discovery Matters

This discovery is important for several reasons. First, it deepens our understanding of how the Maya viewed games—not as mere distractions, but as important rituals and markers of social status. By embedding the Patolli gameboard into the very fabric of their homes and public spaces, the Maya reinforced the game’s significance in the broader context of their culture.

Additionally, the mosaic Patolli board challenges the traditional understanding of Maya architecture and design. Unlike earlier findings, where gameboards were simply etched or painted onto walls, this board’s integration into the floor’s mortar shows that the game was valued enough to be considered an essential part of a building’s overall design.

Most importantly, the discovery helps us see the Maya not just as builders of monumental temples and palaces, but as a people who integrated play, community, and spirituality into the physical spaces they inhabited. By uncovering this gameboard, we don’t just learn about an ancient pastime; we gain insight into the daily lives, social structures, and belief systems of one of the most fascinating civilizations in human history.

The story of this gameboard at Naachtun is not just about the past—it’s about how a small, seemingly simple discovery can change the way we view an entire culture, and the lasting significance of games in the shaping of human society.

More information: Julien Hiquet et al, Dealing with Uniqueness: A Classic Period Maya Mosaic CeramicPatolliBoard from Naachtun, Guatemala, Latin American Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.1017/laq.2025.10125