Stress is often thought of as a fleeting feeling—a racing heart before a test, sweaty palms before speaking in class, or the nervous energy of trying something new. For children, though, stress can be far more than a temporary state of mind. Research led by Duke University scientists, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals that childhood stress does not simply fade away. Instead, it can seep into the body itself, leaving lasting imprints that shape a person’s physical health well into adulthood.

Co-author Herman Pontzer, professor of evolutionary anthropology and global health at Duke, described it this way: “It gets underneath the skin, and it becomes embodied in the way your body handles stress.” The idea has been around for decades, but this new study provides some of the clearest evidence yet that stress experienced in early life sets the stage for future health outcomes.

Measuring Stress, Not Just Remembering It

One of the challenges in understanding stress has always been how to measure it. Many past studies relied on adults recalling their childhood experiences, a method prone to bias or memory gaps. What makes this research unique is its reliance on hard data collected across years.

Lead author Elena Hinz, a Ph.D. student in Pontzer’s lab, analyzed information from the Great Smoky Mountains Study, a landmark longitudinal project that began in 1992 and continues today. This study followed children in rural North Carolina over decades, gathering not only surveys but biological samples—blood tests, health checkups, and physical measurements—allowing researchers to trace the direct physiological effects of stress from childhood into adulthood.

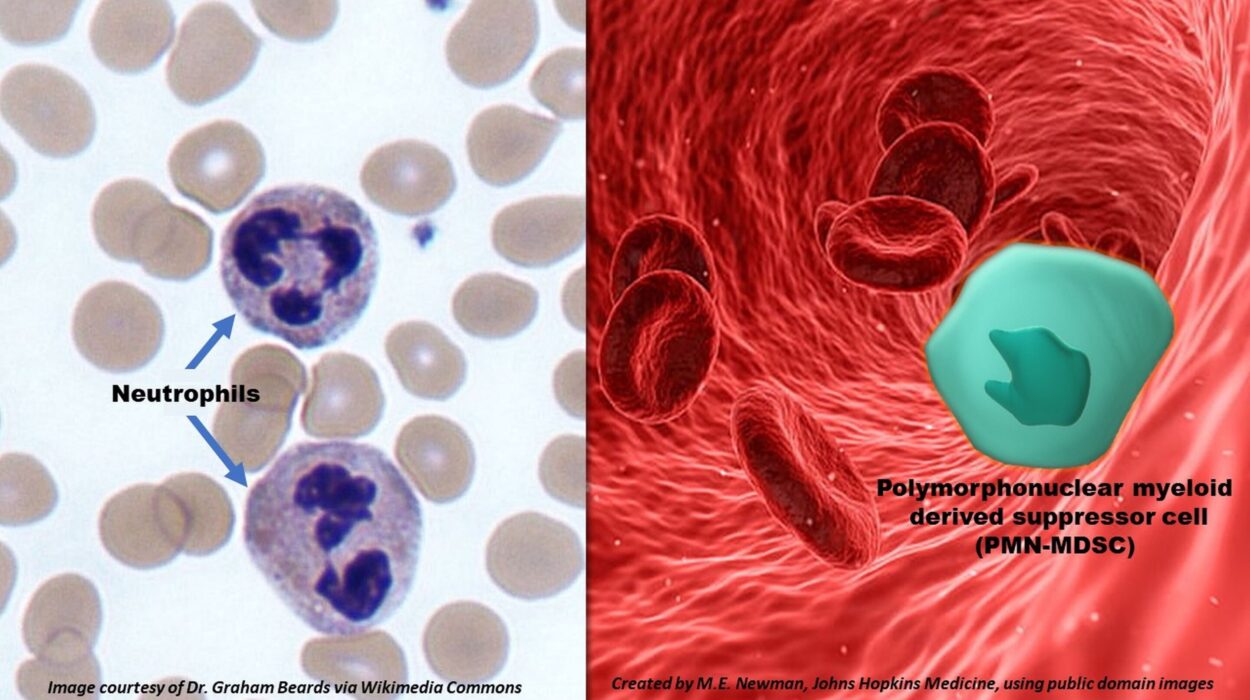

Instead of asking adults to remember how stressful their youth was, Hinz and her colleagues looked at measurable biomarkers of stress in children as young as 9 to 11. They examined indicators like C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation), the presence of Epstein-Barr virus antibodies (showing how stress weakens immune control), body mass index, and blood pressure. These factors gave researchers a clear picture of a child’s allostatic load—the wear and tear on the body caused by chronic stress.

The Wear and Tear of Allostatic Load

Allostatic load, often called the body’s “stress burden,” is a way of describing what happens when the fight-or-flight response never truly switches off. In small doses, stress can be helpful—it sharpens focus, prepares the body to react, and can even save lives in dangerous situations. But when stress is constant, the body pays a heavy price.

Elevated blood pressure, increased heart rate, suppressed immune function, and chronic inflammation become the new normal. Over time, these changes increase the risk of cardiometabolic diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. The Duke study shows that children with high allostatic load were far more likely to experience poor cardiovascular and metabolic health as adults.

Hinz put it simply: “Your body reacts by increasing your heart rate and blood pressure when you are experiencing a stressful situation. Those responses help you deal with stress, but it’s not good to always be in that state.”

Childhood Poverty at the Heart of the Problem

The study highlights a powerful and troubling truth: stress is not evenly distributed. Poverty is a central driver of childhood adversity, creating environments where children may face uncertainty about food, unstable housing, exposure to violence, or limited access to health care.

Pontzer emphasized that the daily struggles of children in poverty—wondering whether there will be dinner on the table, worrying about safety, lacking stable support systems—are not just emotional burdens. These stresses alter the very way a child’s body functions, setting biological patterns that may last a lifetime.

For Hinz, who grew up in rural East Tennessee, the research resonates on a personal level. She explained that her interest was shaped by firsthand observations of how economic hardship influences childhood stress: “I have this idea of what stress looks like in that environment, in terms of childhood adversity and dietary stress and the physical environment that kids are in.”

Why This Study Matters

The findings offer both a warning and a call to action. If stress leaves biological footprints so early in life, then supporting children in their most formative years becomes not just an issue of education or mental health, but a matter of long-term physical well-being.

Pontzer underscored the importance of addressing root causes, saying, “What helps is education and job training and all of the stuff that gets communities out of poverty. That gets people the help they need when they need it, as opposed to health care cost barriers.”

In other words, preventing chronic disease may start not in hospitals but in classrooms, kitchens, and neighborhoods. Ensuring that a child grows up in a stable environment with reliable access to food, safe housing, and supportive community networks is one of the strongest forms of preventive medicine.

Toward a Healthier Future for Children

The research paints a sobering picture of how childhood experiences shape adult health, but it also points to hope. Stress, while powerful, is not destiny. Interventions that reduce poverty, expand access to mental health support, and provide children with nurturing, stable environments can interrupt the cycle of adversity.

Every child deserves the chance to grow in an environment where their bodies are not locked in constant defense mode. When children are free from the relentless strain of chronic stress, they are not only healthier in the present—they are far more likely to grow into adults with stronger hearts, healthier metabolisms, and brighter futures.

The Duke study reminds us of something simple yet profound: stress is more than a feeling. It is a biological force that shapes who we become. And by protecting children from the crushing weight of chronic stress, we protect the health of generations to come.

More information: Elena Hinz et al, Childhood allostatic load predicts cardiometabolic health in adulthood, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2508549122