In the cool, dusty storage rooms of the National Museum of Copenhagen, a forgotten collection from a 1930s excavation quietly waited to be rediscovered. For nearly a century, ceramic fragments gathered from the ancient Syrian town of Hama had remained unidentified—puzzling remnants from a time before written history. But when Dr. Georges Mouamar examined the box labeled “miscellaneous,” something clicked. The shapes, textures, and hollow handles looked startlingly familiar. He had seen objects like these before—not in academic texts, but on the shelves of the National Museum in Damascus: ancient clay rattles.

Thus began a journey into the early Bronze Age world of children, play, and domestic life in the northern Levant. The findings, published in the journal Childhood in the Past, represent the largest securely identified assemblage of ancient rattles from the Near East to date—nineteen fragments, all traced to the Early Bronze IV period (circa 2500–2000 BCE). More than mere curiosities, these objects have opened an unprecedented window into the overlooked lives of the youngest members of ancient society.

Rattles Reimagined: Piecing Together Forgotten Childhoods

The rattles from Hama, once miscategorized or entirely ignored, are now understood as part of a broader research effort led by Dr. Mette Hald, whose project focuses on everyday life in ancient Syria. “We’re looking at food practices, trade, and crafts,” she explains, “but we also focus on the lives of children.” Until now, the archaeology of childhood has often remained in the shadows—overshadowed by temples, palaces, and battle narratives. But as these fragments show, the echoes of infant laughter and sibling games have always been part of humanity’s story.

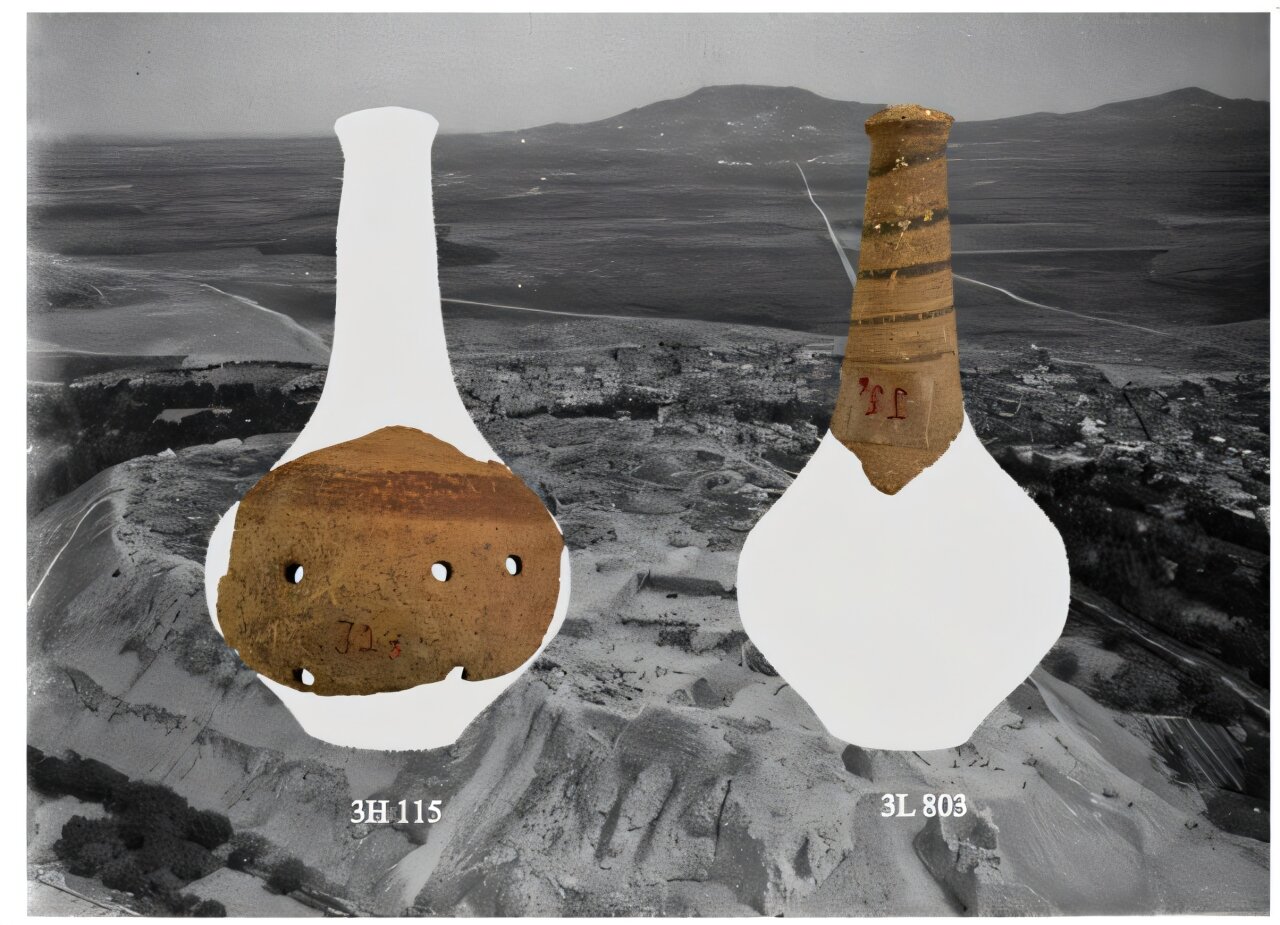

What makes the rattles from Hama so significant is not only their number but their form. Most are hollow handles—small, cylindrical, and easy to grip. Their surfaces bear the fingerprints of ancient artisans: some are painted with bold dark lines, spirals, and diagonal motifs, while others remain plain, undecorated. Most feature a protruding knob or flat base, and a rare few possess a rounded end. Measuring between 4.5 and 6 centimeters in length and only 2 centimeters in diameter, these rattles were ideally sized for an infant’s chubby fingers—or for the hands of an older sibling keeping a baby entertained.

Ancient Toys or Ritual Tools?

The role of rattles in ancient societies has long puzzled archaeologists. Were they toys, musical instruments, or ritual tools? The evidence from Hama suggests they were likely multifunctional, though in this case, their domestic context provides the strongest clues. Found within household neighborhoods, the rattles appear to have been deeply embedded in everyday life rather than religious or elite rituals.

Experimental studies on similar intact rattles from the nearby site of Al-Zalaqiyat support this interpretation. These objects, too, contained small pebbles sealed inside their hollow clay bodies. The sound they made—soft and subdued—resembled that of modern plastic baby rattles. Too gentle to be heard over drums or chants in a temple, but perfect for engaging a baby without overwhelming them.

“The material inside is of stone or baked clay,” explains Dr. Hald. “It doesn’t degrade over time, and the holes in the rattle’s body are too small for it to fall out. That’s why these have survived so well.” The design was functional and intentional, crafted with knowledge passed from one potter to another—possibly over generations.

A Changing City, a Growing Population

The appearance of these rattles in level J6 at Hama coincides with a dramatic transformation in the city’s layout. Archaeological evidence indicates a shift from a spacious, open-plan urban design with wide avenues to a denser arrangement of narrow alleyways and compact buildings. This structural change suggests a growing population, with more families and, naturally, more children.

In such a bustling settlement, parents—especially mothers—would have been busy with daily tasks outside the immediate household. Rattles, then, served a vital function: soothing fussy babies, entertaining toddlers, and even helping older siblings manage childcare duties. Far from being luxury items, these rattles were likely standard fare, produced by local potters and bought or bartered as part of the domestic toolkit.

It’s even possible that they were part of birth rituals or given as gifts to new mothers—functional items that doubled as symbols of love and community support. But their true magic lay in their sound: the soft clatter of pebbles echoing through cramped courtyards and stone-walled homes, a sonic thread tying the ancient city together.

A Northern Levantine Signature

The rattles from Hama are not alone in the archaeological record. Similar handled rattles have been uncovered at Al-Zalaqiyat, Qatna, Tell ‘As, and Tell Araq—forming what researchers are now identifying as a distinct northern Levantine variant. These rattles differ from the zoomorphic and handle-less types found elsewhere in the broader Near East. They speak of a shared cultural practice across northern Syria, perhaps even a regional market of potters crafting these gentle instruments for parents and caregivers.

The decorations on some rattles suggest more than just function. Painted bands—red, black, or buff—and spirals may have served aesthetic or symbolic purposes. Whether these designs were merely decorative or imbued with meaning, they signal an attention to detail and a desire to make something beautiful for children—perhaps a way to brighten the long hours of infancy or ward off ill fortune.

Sounding the Past: What a Rattle Reveals

For archaeologists, the discovery is more than just an addition to the museum catalog. It’s a transformation of how we understand ancient life. Too often, the material record focuses on the monumental: kings and wars, tombs and temples. But the rattle is humble and intimate. It belongs not to the elite but to the everyday—to mothers, fathers, siblings, and infants whose lives rarely leave a trace in stone or text.

“These rattles give voice to the voiceless,” says Dr. Hald. “They’re part of a broader effort to reimagine ancient societies not just through their elites, but through the full spectrum of human experience.” In doing so, the study of these artifacts adds depth to our picture of the Early Bronze Age, showing that even amid the chaos of urban growth and trade, the needs of children remained constant—and were met with love, care, and craft.

A Future for Forgotten Childhoods

The study of ancient childhood is still in its infancy, but discoveries like the Hama rattles suggest a promising future. As more collections are reexamined and new sites excavated, archaeologists are beginning to ask new questions: What toys did children play with? What games did they invent? How were they cared for, trained, or disciplined? What was it like to grow up in a mudbrick house in Bronze Age Syria?

Dr. Hald and her team plan to continue looking for clues—objects that may have been overlooked simply because they were small or ambiguous. “We’ll certainly keep our eyes peeled,” she says, “for other items from Hama which might relate to children, as this is something that has often been overlooked.”

What the rattles of Hama remind us is that archaeology is not just about kings and gods. It’s about the quiet rhythms of daily life: the rattle in a baby’s hand, the laughter of a child in a courtyard, the hum of a city that was once full of life. These small sounds ripple through time, waiting patiently to be heard again.

Reference: Georges Mouamar et al, Infant Care in Early Bronze Age Syria: Newly Identified Clay Rattles at Hama, Childhood in the Past (2025). DOI: 10.1080/17585716.2025.2489258