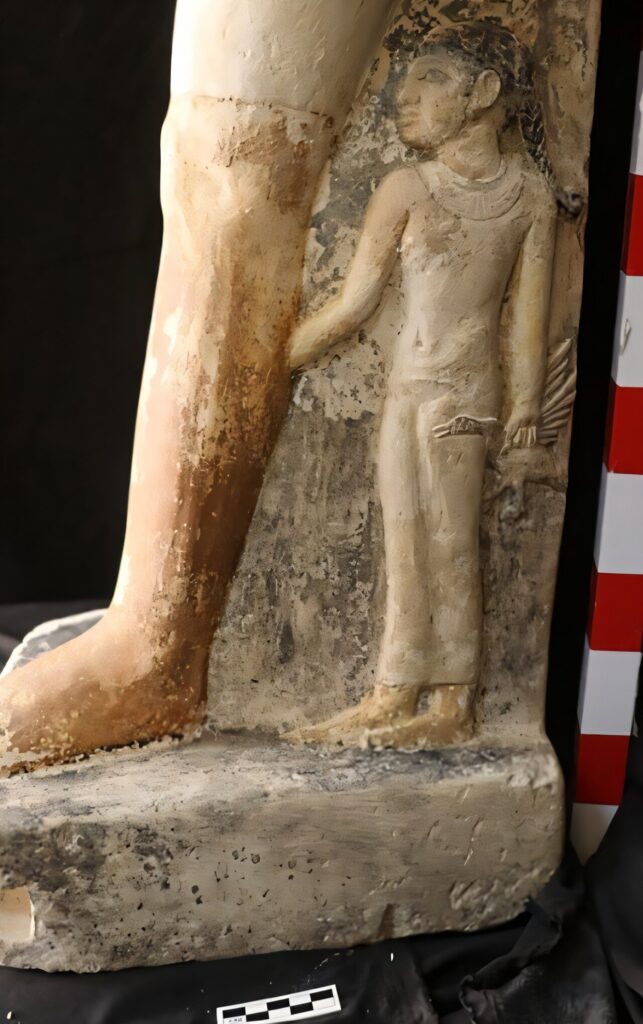

In 2021, archaeologists working at Gisr el-Mudir, one of the oldest stone structures in Saqqara, unearthed something extraordinary. Buried beneath the desert sands lay a limestone statue unlike any other known from ancient Egypt. Though damaged and stripped of its original context, the statue radiates a powerful sense of presence, offering an intimate window into the lives, traditions, and artistic innovations of Egypt’s Old Kingdom.

The find was recently described in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology by Dr. Zahi Hawass and Dr. Sarah Abdoh, who carefully documented its unusual composition and cultural significance. More than just a work of art, the statue embodies the ideals of family, devotion, and eternal life that defined the ancient Egyptian worldview.

The Nobleman: Strength and Vitality in Stone

At the heart of the statue stands a nobleman, his form sculpted with striking attention to detail. He stands tall, left foot forward—a pose deeply rooted in the artistic traditions of the Old Kingdom. This deliberate stance symbolized vigor, readiness, and the eternal stride into the afterlife.

The nobleman’s attire further reflects his status and dignity. He wears a short, locked wig, carefully carved to emphasize refinement, and a half-goffered kilt, a garment often associated with elite men of the period. The sculptor devoted particular attention to his upper body, rendering the curve of his shoulders, the subtle outline of his clavicle, and the strong definition of his pectorals and arms. This realism was not mere artistry; it was a declaration of his vitality, ensuring that he would be eternally youthful in the afterlife.

The Wife: Devotion at Her Husband’s Side

Beside him, but sculpted on a much smaller scale, is a woman—most likely his wife. She kneels gracefully, her arms wrapped around his leg, her cheek resting gently against it. She wears a shoulder-length wig, a broad collar, and a tight-fitting sheath dress, a style typical of women in the Old Kingdom.

Her smaller size does not diminish her importance. In Egyptian art, the wife’s embrace symbolized not only affection but also unity, loyalty, and eternal companionship. She is depicted as the supportive partner, her presence completing the image of the family. Similar scenes can be found in other statues, such as the royal statue of Djedefre, where queens are shown embracing their husbands in much the same way.

Her intimate gesture conveys tenderness, a reminder that these statues were not only monuments to social status but also deeply personal representations of love and connection.

The Daughter: A Unique Innovation

What truly sets the Gisr el-Mudir statue apart is the third figure: a young girl, likely the nobleman’s daughter. Unlike her parents, she was not carved fully in the round. Instead, her image was created in bas-relief, etched into the stone surface behind her father’s left leg.

This artistic choice is unprecedented in Old Kingdom family statuary. The girl extends her right arm forward, grasping her father’s leg, while her other hand holds a goose. The goose is a powerful symbol, likely representing food provisions for the afterlife. Normally, such offerings would be shown in wall reliefs inside tombs, but since no decorated walls survive in the nobleman’s burial place, this detail carved directly into the statue may have served the same symbolic function.

Dr. Hawass explains that during the Old Kingdom, children were often represented in tomb scenes bringing food and animals for their parents in the afterlife. Here, the daughter holding a goose may be fulfilling that same ritual role, ensuring her father’s eternal sustenance.

The choice to carve her in bas-relief instead of three-dimensional form remains a mystery. No other family statue from this period is known to have used this technique, making the Gisr el-Mudir statue a singular example of artistic experimentation in ancient Egypt.

A Puzzle Without Context

The statue was discovered without its original archaeological context. It had been abandoned in the sand, likely discarded or dropped by tomb robbers who once looted nearby burials. This loss of context makes dating the piece more difficult, as archaeologists often rely on tomb architecture, inscriptions, or associated objects to establish a timeline.

Instead, scholars turned to stylistic analysis, comparing the nobleman and his family to other known statues from Saqqara. This comparative approach offered vital clues to its age and origins.

The Connection to Irukaptah

Among the most compelling comparisons is the limestone statue of Irukaptah, housed today in the Brooklyn Museum. Dating to the 5th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, Irukaptah’s statue shares striking similarities with the Gisr el-Mudir piece.

In both statues, the nobleman strides forward with his left leg, wearing similar clothing and wig styles. In both, the wife kneels by his side, depicted on a smaller scale and embracing his leg. In Irukaptah’s statue, the couple’s son is carved in the round, standing nearby with a finger to his mouth—a gesture often used to depict children.

The Gisr el-Mudir statue mirrors these elements almost exactly, with one crucial difference: instead of a son, a daughter is present, and she is depicted in bas-relief. The close similarity in proportions, posture, and craftsmanship suggests that both statues may have been produced in the same artistic workshop during the 5th Dynasty.

A Family Immortalized

Taken together, the Gisr el-Mudir statue offers an intimate glimpse into the values of the Old Kingdom elite. It reflects the Egyptian ideal of family unity—the strong and eternal husband, the loyal and supportive wife, and the dutiful child providing sustenance for eternity.

But more than that, it shows a moment of artistic creativity, a willingness by the sculptor to bend tradition by rendering the daughter in bas-relief. This unusual choice has immortalized not only the family it represents but also the individuality of the artist and the community that commissioned the work.

The Legacy of a Unique Statue

The Gisr el-Mudir statue is more than a piece of limestone. It is a narrative frozen in time—a father, mother, and daughter bound together in stone, their gestures filled with meaning, their roles carefully chosen to ensure eternal life. It reminds us that behind the grandeur of pyramids and temples, ancient Egypt was built on families, relationships, and love.

Its uniqueness lies not only in its artistic innovation but also in the way it bridges personal intimacy with cosmic belief. In one single monument, the ideals of strength, devotion, and provision are carved into eternity.

Though it was left forgotten in the sands, its rediscovery allows the nobleman, his wife, and his daughter to once again step forward—together—into history.

More information: Zahi Hawass et al, Family Statue from Gisr el-Mudir (Saqqara), The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1177/03075133251329948