For generations, the story of Venetian glass has begun with fire. It has opened in the furnaces of Murano, glowing in the late Middle Ages, where artisans coaxed molten brilliance into forms that would dazzle Europe. That image is so powerful that it has long erased what came before, casting the earlier centuries as a dim prologue rather than a story worth telling on its own. Yet history has a way of resurfacing in unexpected forms. In this case, it returned not as a masterpiece but as fragments—small, worn pieces of glass pulled from the soil of an ancient island, quietly insisting that Venice’s relationship with glass began far earlier, and far more boldly, than anyone had assumed.

These fragments, recovered from San Pietro di Castello on the island once known as Olivolo, have transformed how scholars understand Early Medieval Venice. They suggest that long before Murano’s fame, the lagoon city was already technologically adept, internationally connected, and deeply involved in the evolving science of glassmaking. The past that emerges from this evidence is not tentative or provincial. It is confident, experimental, and plugged into the wider Mediterranean world.

An Island at the Threshold of the Lagoon

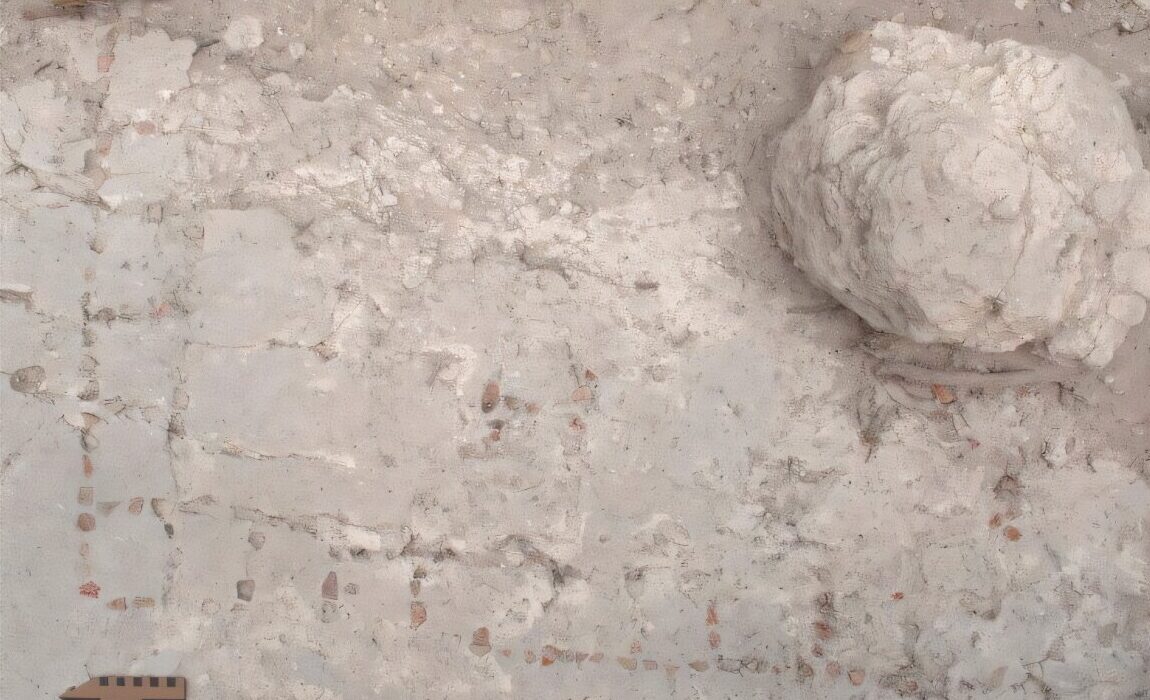

San Pietro di Castello was no ordinary settlement. As one of Venice’s founding nuclei, it occupied a strategic position near the entrance to the harbor, controlling access to the lagoon itself. In the Early Middle Ages, this location placed it at the threshold between land and sea, between local life and international movement. When archaeological excavations were carried out there in the early 1990s by the Superintendency for Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the Metropolitan City of Venice, few could have predicted how consequential the findings would become decades later.

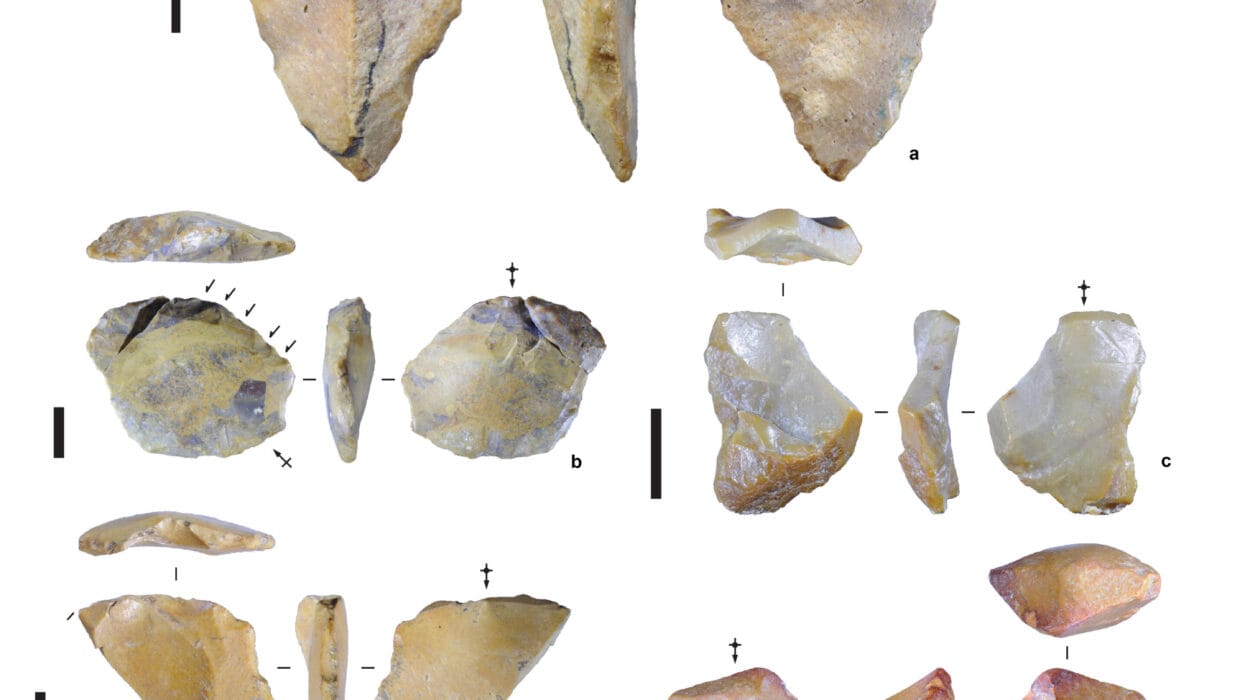

From those excavations came an assemblage of Early Medieval glass fragments, eventually numbering forty-five samples. They included vessels, waste from glass production, and even a steatite crucible, tangible evidence that glass was not merely arriving in Venice but was being actively worked there. Dated between the sixth and ninth centuries, these remains sat quietly in storage until new analytical techniques could ask more ambitious questions of them.

Those questions were taken up in an archaeometric study published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences by Margherita Ferri of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, in collaboration with Elisabetta Gliozzo of the University of Florence and Eleonora Braschi of the CNR Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources. Their work did not simply catalog the fragments. It interrogated their chemical composition, their origins, and their technological implications, opening a window onto a Venice that had been hiding in plain sight.

When Glass Changed Its Recipe

One of the most consequential shifts in ancient technology was a change in how glass itself was made. For centuries under the Roman Empire, glassmakers relied on natron, a mineral sourced primarily from Egypt, as a key ingredient. When access to Egyptian natron became difficult, glassmakers across Europe were forced to adapt. The solution was plant ash, a new base material that ushered in a different kind of glass and marked a turning point in the craft’s history.

For archaeologists, a central question has long been who first embraced this new technology and how quickly it spread. The answer emerging from San Pietro di Castello has rewritten that narrative.

“The answer emerging from the excavations at San Pietro di Castello is surprising,” explains Margherita Ferri.

“Here we have fragments of plant-ash glass dating back as early as the 8th century. But the real twist is another: chemical analysis attributes these ancient fragments to Syro-Levantine production. This means that Venice, 1,300 years ago, not only was aware of this new technology, but its trade networks were so efficient that it imported cutting-edge materials produced hundreds of kilometers away. This places Venice among the very first centers in Italy to embrace and master this technology, revealing a remarkably receptive and well-connected city.”

These words carry weight because they reposition Venice within the technological geography of the Early Middle Ages. Rather than lagging behind innovation, the city appears to have been actively seeking it out, acquiring advanced materials from the Syro-Levantine world and integrating them into local practice at a remarkably early date.

Old Knowledge Melted into the New

The story becomes even more intriguing when one looks closely at a single blue mosaic tessera recovered from the site. Chemical analysis revealed that it contained two different opacifying agents. One was calcium antimonate, a technique rooted in ancient tradition and no longer used after the fourth century. The other was lead stannate, a more modern innovation.

The coexistence of these two technologies within a single object initially seems impossible, as if centuries had somehow collapsed into one tiny square of glass. Yet the explanation that emerges is both elegant and revealing. Early Medieval craftspeople were recycling. They melted down an older Roman tessera, reclaiming its material and blending it with newer methods to produce something fit for their own time.

This act of reuse speaks volumes. It shows an intimate understanding of materials, a respect for the value embedded in older objects, and a willingness to combine inherited knowledge with contemporary innovation. The same sensibility appears in the production of blue glass more broadly. Rather than relying on pure, refined cobalt pigment, Venetian artisans exploited metalworking slag rich in cobalt, a by-product of another craft entirely. This choice was not accidental. It reflects a sophisticated awareness of material properties and an economy that minimized waste by turning leftovers into resources.

What emerges is an image of Early Medieval Venice practicing something akin to a proto–circular economy, long before the term existed. Innovation here did not mean discarding the past. It meant melting it down and reshaping it.

A City Woven into the Mediterranean

The chemical fingerprints preserved in these glass fragments also map the trade routes that sustained Venice. Analyses of raw glass provenance reveal an almost equal presence of material from Egypt and from the Levant, regions that were the primary centers of glass production at the time. This balance suggests not a single dominant supply line but a flexible, responsive network that could adapt to changing geopolitical and economic conditions across the Mediterranean.

Venice, in this light, was not a passive endpoint for goods drifting westward. It was an active node in a complex web of exchange, capable of sourcing materials from multiple regions and integrating them into its own economic and cultural life. The lagoon’s position allowed it to participate dynamically in long-distance trade while maintaining strong local production.

The glass itself preserves clues to how these exchanges functioned. Plant-ash beakers, for instance, reveal a fascinating duality. Their chemical composition points to Syro-Levantine raw material, yet their shapes match those of beakers produced locally using the older natron-based recipe. This combination indicates that Venetian artisans imported raw glass and then worked it into forms that suited local tastes and traditions.

At the same time, the presence of a conical-based glass, common in Syrian production but not made in the Adriatic during that period, signals the direct import of finished luxury goods. These objects arrived not to be reworked, but to be used and displayed as they were.

The Intelligence of a Mixed Supply Chain

Together, these findings reveal a supply system of remarkable sophistication. Early Medieval Venice was importing raw materials for its workshops while also acquiring high-value finished objects for immediate consumption. This mixed strategy suggests careful economic planning and a nuanced understanding of when it was advantageous to produce locally and when it was better to rely on external expertise.

Such a system requires more than ships and merchants. It requires knowledge—of materials, of markets, and of technologies developing far beyond the lagoon. The glass from San Pietro di Castello demonstrates that this knowledge was present in Venice centuries before the rise of Murano’s legendary furnaces.

Why These Fragments Change the Story of Venice

The significance of this research extends far beyond the history of glass. It reshapes how we understand the origins of Venice itself. The city that emerges from these analyses is not a marginal settlement slowly finding its footing. It is a lively hub of international trade and technological progress, already advanced, connected, and innovative by the eighth century.

By tracing the movement of glass and the techniques embedded within it, this study reveals Venice as a key center in the Early Medieval Mediterranean, capable of mastering the most sophisticated technologies of its era. It shows a society willing to adopt new methods, reuse old materials, and engage deeply with distant regions through commerce and craft.

Most importantly, it reminds us that history often survives in the smallest things. A shard of glass, chemically analyzed centuries after it was last held in human hands, can overturn long-held assumptions and restore forgotten chapters to the human story. In the case of Venice, these fragments illuminate a city already shining brightly long before its fame caught up with it.

More information: Elisabetta Gliozzo et al, The glass assemblage from San Pietro in Castello: tracing glass technology and innovations in the Venetian lagoon, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s12520-025-02317-0