The story began the way many astronomical discoveries do: with something that looked ordinary at first glance. A bright point of light appeared in images taken by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, shining within the dusty surroundings of a nearby star. Astronomers had seen similar things before. In distant planetary systems, a faint glow often means a planet, its surface or atmosphere reflecting starlight back toward Earth.

So that is what the scientists assumed. They believed they were looking at a dust-covered exoplanet, quietly orbiting its star. Nothing about it seemed urgent. Nothing suggested catastrophe.

Then the light vanished.

In its place, another bright object appeared, close by but unmistakably new. It was as if the universe had blinked, erased one presence, and written another into the same cosmic neighborhood. The change was too dramatic to ignore. Slowly, realization dawned among the international team studying the system. These were not planets at all.

They were wreckage.

The Moment Astronomers Realized the Universe Had Crashed

“Spotting a new light source in the dust belt around a star was surprising. We did not expect that at all,” said Jason Wang of Northwestern University, one of the researchers who had been watching this system for years.

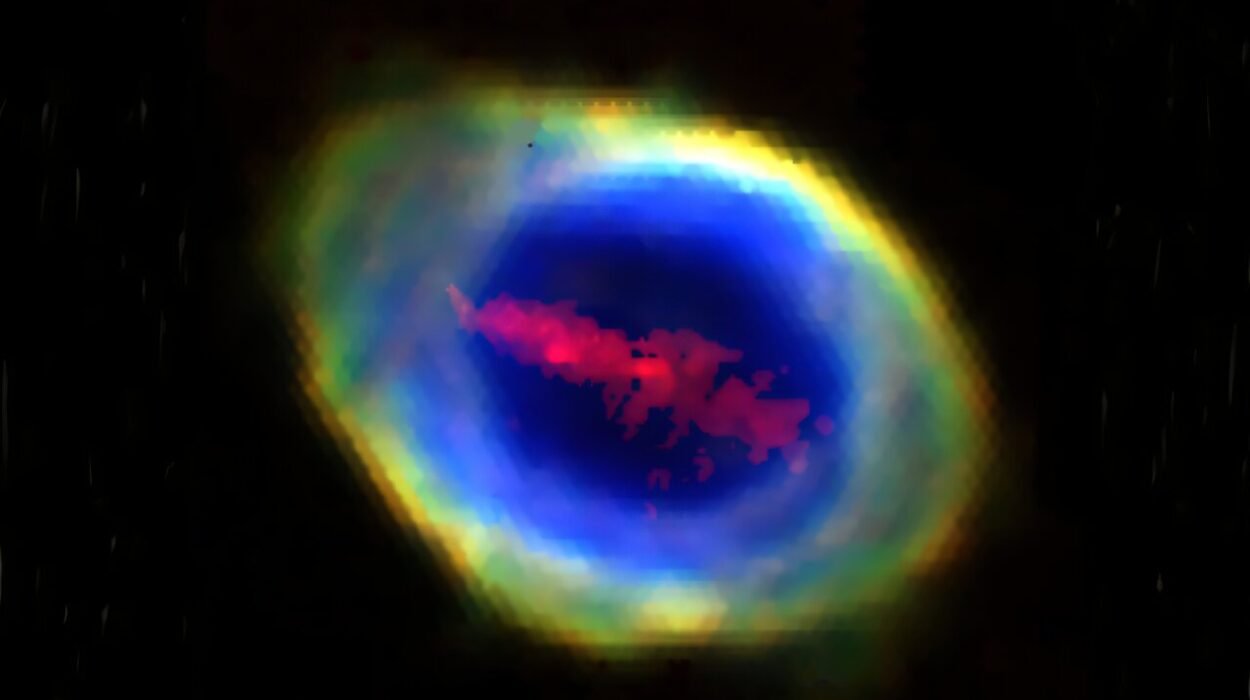

The star in question is Fomalhaut, a luminous neighbor just 25 light-years away in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. It is more massive than our sun and surrounded by an elaborate structure of dusty debris belts. For decades, astronomers have studied this system because its brightness and proximity make it unusually easy to observe.

“The system has one of the largest dust belts that we know of,” Wang explained. “That makes it an easy target to study.”

Easy, perhaps, but not simple.

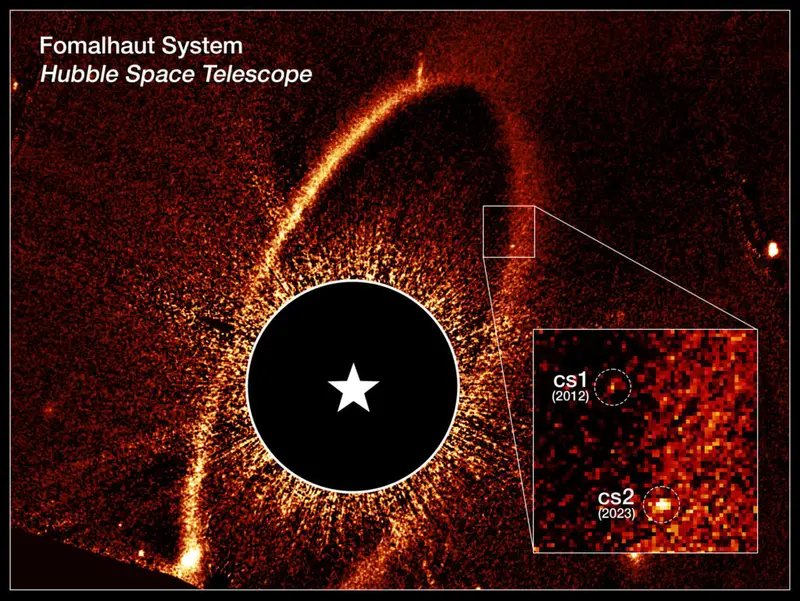

Since 2008, scientists had been puzzling over a mysterious object called Fomalhaut b. It appeared just outside the star’s main dust belt and glowed faintly in Hubble’s images. Was it a real planet, or something else entirely? The question lingered for years without a definitive answer.

When Hubble observed the system again in 2023, the answer arrived in the most unexpected way. Fomalhaut b was gone.

When a Planet Candidate Became a Ghost

“With these observations, our original intention was to monitor Fomalhaut b, which we initially thought was a planet,” Wang said.

“We assumed the bright light was Fomalhaut b, because that’s the known source in the system. But, upon carefully comparing our new images to past images, we realized it could not be the same source. That was both exciting and caused us to scratch our heads.”

The original light source had faded completely. In its place, another point of light appeared slightly offset, glowing with a similar intensity. The pattern felt eerie, almost theatrical, as if the system itself were replaying a scene.

Lead author Paul Kalas of the University of California, Berkeley, remembers the shock clearly.

“This is certainly the first time I’ve ever seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system,” he said.

“It’s absent in all of our previous Hubble images, which means that we just witnessed a violent collision between two massive objects and a huge debris cloud unlike anything in our own solar system today.”

The team renamed the vanished object Fomalhaut cs1 and the new one Fomalhaut cs2. The “cs” stands for circumstellar source, a careful nod to the fact that neither object could confidently be called a planet anymore.

What they were seeing, the researchers concluded, were the illuminated remains of two separate cosmic smashups.

A Cosmic Fender Bender on an Unimaginable Scale

The researchers’ primary hypothesis was both startling and elegant. Over the past two decades, two separate collisions had occurred in the same planetary system. Each collision involved planetesimals, small rocky bodies similar to asteroids that serve as the building blocks of planets.

“Our primary hypothesis is that we saw two collisions of planetesimals—small rocky objects, like asteroids—over the last two decades,” Wang said. “Collisions of planetesimals are extremely rare events, and this marks the first time we have seen one outside our solar system.”

When planetesimals collide at high speeds, they do not simply crack or crumble. They explode into vast clouds of dust and debris that can briefly shine as brightly as a planet, reflecting starlight across space. Over time, those clouds spread out and fade, becoming invisible once more.

That fading explained why Fomalhaut cs1 had disappeared. Its debris cloud had simply thinned too much to detect.

But the appearance of cs2 suggested something even more astonishing: another collision had occurred, producing a fresh cloud that now glowed in the dust belt.

Two Collisions Where There Should Have Been One

The implications were staggering. According to existing theory, such planetesimal collisions should be exceedingly rare.

“Theory suggests that there should be one collision every 100,000 years, or longer. Here, in 20 years, we’ve seen two,” Kalas said.

He offered a vivid way to imagine it.

“If you had a movie of the last 3,000 years, and it was sped up so that every year was a fraction of a second, imagine how many flashes you’d see over that time. Fomalhaut’s planetary system would be sparkling with these collisions.”

The idea that astronomers just happened to catch not one but two of these events in such a short observational window seemed almost unbelievable. That made careful verification essential.

Wang played a key role in confirming the finding. He conducted one of four independent analyses designed to ensure the signals were real and not artifacts or errors.

“This is the first time we’re seeing something like this,” Wang said. “So, we had to make sure we can trust our images and that we are measuring the properties of the collision properly. I crunched the numbers to show that the four independent analyses all confidently detect a new source around the vicinity of the star.”

Only after that rigorous confirmation did the team allow themselves to embrace the conclusion. They had not discovered planets. They had witnessed destruction in real time.

Why Colliding Rocks Matter to Planetary Science

At first glance, watching asteroids crash into each other might seem like cosmic trivia. But to planetary scientists, these violent events are deeply meaningful.

“Studying planetesimal collisions is important for understanding how planets form,” Wang said. “It can also tell us about the structure of asteroids, which is important information for planetary defense programs like the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART).”

Planets are born from chaos. In young planetary systems, countless rocky bodies collide, merge, and shatter, gradually assembling into larger worlds. By observing collisions as they happen, astronomers gain rare insight into the raw processes that shape planets long before they become stable and serene.

In the Fomalhaut system, the collisions also offer clues about the internal structure of the planetesimals involved. The way debris spreads and reflects light depends on the size, strength, and composition of the parent objects. Each dust cloud is a forensic record written in starlight.

A Warning for the Future of Exoplanet Hunting

The discovery also carries a quiet warning.

“Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an extrasolar planet reflecting starlight,” Kalas said. “What we learned from studying cs1 is that a large dust cloud can masquerade as a planet for many years. This is a cautionary note for future missions that aim to detect extrasolar planets in reflected light.”

As astronomers prepare for a new era of planet hunting, with next-generation observatories designed to directly image Earth-like worlds, the risk of mistaking debris clouds for planets becomes more serious. A glowing dust cloud can convincingly imitate a planet’s signature, lingering long enough to fool even careful observers.

The Fomalhaut system serves as a cosmic reminder that not every point of light is a world. Some are scars.

Watching the Aftermath With New Eyes

Although Hubble revealed the collisions, its aging instruments can no longer provide the detailed data needed to study them further.

“Due to Hubble’s age, it can no longer collect reliable data of the system,” Wang said.

Fortunately, a successor waits in orbit.

The team has secured observing time with the James Webb Space Telescope, using its Near-Infrared Camera to follow the evolution of Fomalhaut cs2. Unlike Hubble, Webb can collect detailed color information that reveals the size and composition of dust grains, including whether the debris contains water and ice.

“Fortunately, we now have the JWST. We have an approved JWST program to follow up this planetesimal collision to understand the new circumstellar source and the nature of its two parent planetesimals that collided,” Wang said.

The scientists plan to watch as the debris cloud spreads and fades, capturing a slow-motion portrait of destruction and dispersal.

Why This Discovery Changes How We See Other Worlds

This research matters because it transforms a distant star system into a living laboratory. For the first time, astronomers have witnessed the immediate aftermath of planet-building collisions beyond our solar system, not as ancient fossils but as unfolding events.

It reminds us that planetary systems are dynamic, violent places, shaped by impacts that leave lasting marks. It sharpens our ability to distinguish true planets from impostors, ensuring that future discoveries rest on solid ground. And it deepens our understanding of how worlds like our own once emerged from clouds of dust and fire.

Most of all, it shows that the universe is not static. Even now, in systems tens of trillions of kilometers away, rocks collide, debris blooms into light, and entire chapters of planetary history flash briefly into view before fading again.

Thanks to careful observation and a willingness to question first impressions, astronomers caught those flashes. In doing so, they revealed a universe that is still very much in motion, still full of surprises, and still capable of telling stories written in light.

More information: Paul Kalas et al, A second planetesimal collision in the Fomalhaut system, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu6266. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adu6266