For more than a century, the image of Diplodocus has loomed in museum halls as a quiet silhouette of grays and browns. Its vast neck arches toward ceilings, its tail sweeps behind like a grand geological punctuation mark, and its skin—at least in our imagination—tends to be uniformly dull. That vision has lasted because the fossil record has offered so little to contradict it. Skin rarely fossilizes, pigment even less so, and reconstructions have leaned toward caution rather than speculation. But every so often, the ground gives up a clue, and a new story begins to unfold.

In a recent study published in Royal Society Open Science, researchers uncovered one such clue. It comes from a juvenile Diplodocus discovered in Montana’s Mother’s Day Quarry, a site already known among paleontologists for preserving young sauropods. What Tess Gallagher and her colleagues at the University of Bristol found in those small, ancient patches of skin suggests that the creature we thought we understood may have worn a richer palette than anyone expected.

Where Color Sleeps in Stone

To understand why this discovery is surprising, it helps to look closely at melanosomes—tiny organelles within cells that create, store, and move melanin, the pigment responsible for many of the colors seen in skin, hair, eyes, and feathers. In fossils, melanin itself has occasionally been detected, but impressions of melanosomes are far rarer, especially in dinosaurs with scales rather than feathers.

Feathered dinosaurs have provided most of the breakthroughs in fossil coloration. Their preserved melanosomes have allowed scientists to sketch ancient patterns with remarkable confidence, and in some cases even identify iridescence. The study notes, “It is believed that melanosome shape diversity in feathers and hair is a direct result of the effects of high metabolism on the melanocortin system. Melanosome shape diversity has been reported in multiple fossils of feathered dinosaurs, allowing for the color patterning of these animals to be determined from the preserved melanosome impressions.”

But sauropods, those slow-moving giants of the Jurassic, have stood outside this revolution. Until now, there had been no evidence that their skin carried any hint of patterning, only a vague assumption that their bodies were textured, reptilian, and monotone. The Diplodocus skin samples from Montana would challenge that assumption in unexpected ways.

Two Shapes, One Mystery

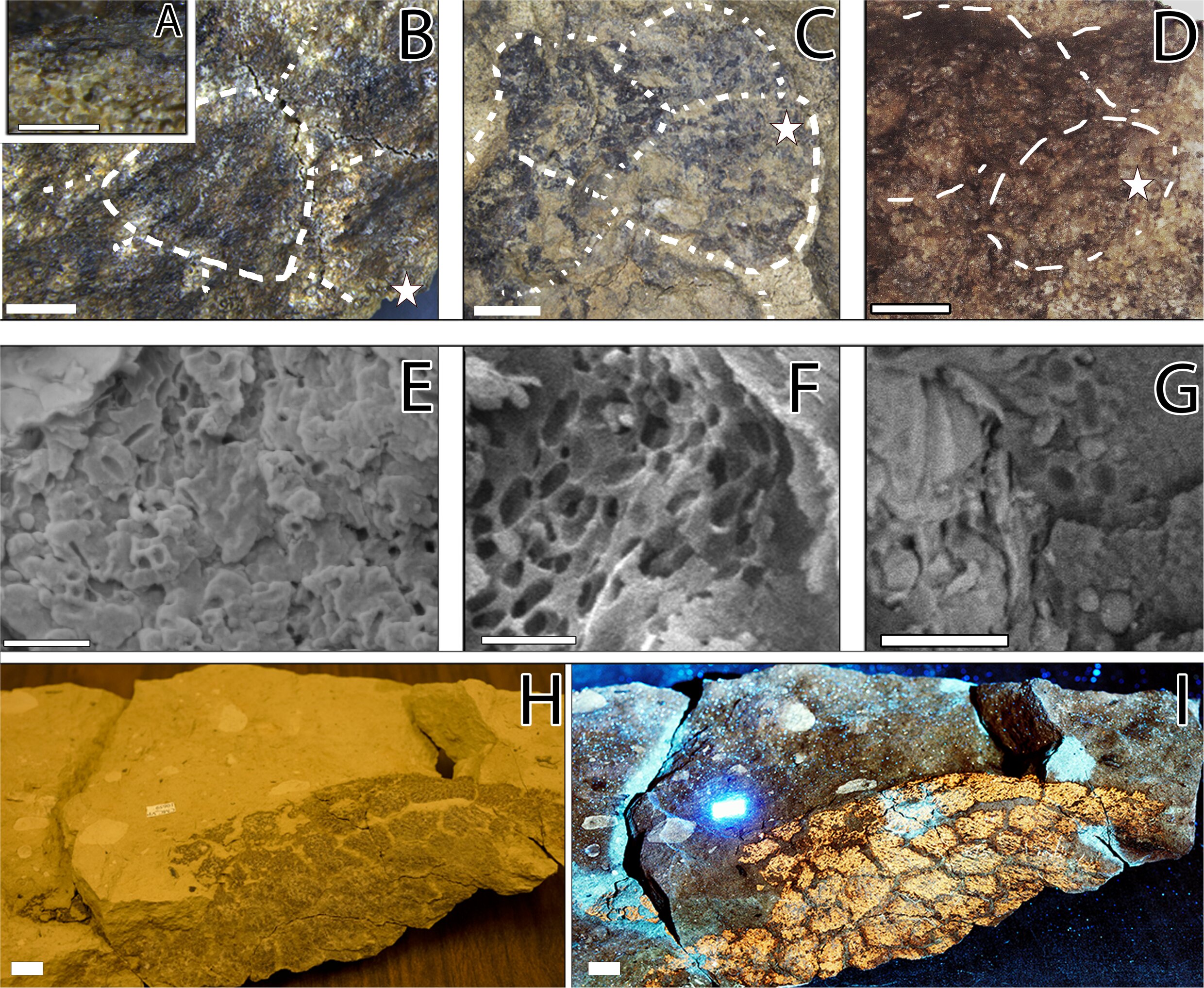

Gallagher’s team turned to scanning electron microscopy and elemental mapping to probe the structure of the fossilized skin. These techniques let them zoom into the landscape of each tiny scale. The analysis revealed carbon-rich layers arranged in forms matching what scientists expect from preserved melanosomes.

More intriguingly, the researchers found not one but two distinct types of microscopic bodies. One was oblong, familiar from other fossilized melanosome impressions. The other was disk-shaped—an oddity not previously recognized in dinosaur scales. Interpreting this second shape required careful comparison with modern and fossil samples.

The authors write, “The closest comparisons that can be made to the disk microbodies are platelet melanosomes in modern bird feathers and the anchiornithid bird Caihong juji, which aid in the production of iridescent colors, as well as oblate retinal melanosomes found in the eye of an Eocene bird. However, it should be noted that these disk-shaped microbodies are smaller than platelet melanosomes, the former averaging 349 nm and the latter 1,000 nm.”

The researchers remain cautious. The identity of the disk-shaped structures is not definitive, but they suspect they represent a form of platelet melanosome. If so, these findings constitute the first evidence of melanosome shape diversity in dinosaur scales—and the first such record within the entire sauropod lineage.

A Skin Speckled With Clues

Coloring the past requires more than identifying shapes; it also requires understanding how those structures were arranged across the skin. The team found that the two potential types of melanosomes were clustered separately within the scales. This pattern hints—very tentatively—at a speckled appearance on parts of the Diplodocus’ body.

Equally important, the sizes of the melanosomes resemble those producing brown or dark colors in modern reptiles and birds. Nothing here suggests vibrant hues or shimmering displays, but it does suggest variation. And variation, even subtle, disrupts the popular vision of sauropods as uniformly gray.

The authors note an important limitation: “While the data in this study are limited to just four specimens of hexagonal scales, making full body color patterning unknown, our results suggest that juvenile sauropods may have possessed diverse and unexpected melanosome morphologies.”

In other words, no one is repainting museum models tomorrow. But the monochrome dinosaur of earlier decades is starting to look less secure.

The Image of a Giant, Redrawn

This discovery does not hand us a complete portrait. It does not tell us exactly how a young Diplodocus blended into its Jurassic environment or how its skin shimmered, mottled, or darkened under the sun. But it offers the first evidence that these colossal animals may have worn patterns stranger and richer than we assumed.

More than anything, the finding pushes back against the idea that sauropods were drab giants. It suggests that even the largest animals of the Mesozoic carried microscopic complexities, subtle variations, and perhaps distinctive markings. That alone reshapes how scientists imagine their lives—how they might have signaled to one another, concealed themselves, or simply grown through stages marked by different appearances.

Why This Discovery Matters

Every fossilized melanosome is a fragment of deep time, a preserved whisper of biology surviving against impossible odds. In the case of Diplodocus, these tiny structures open a rare window into skin rather than bone, revealing a layer of information once thought forever lost. Because skin is where color lives, these findings allow scientists to inch closer to answering one of the most elusive questions in paleontology: What did dinosaurs really look like?

By uncovering two distinct melanosome shapes in sauropod scales for the first time, this study expands the toolbox available for reconstructing the appearance of long-extinct giants. It also signals that the evolutionary story of dinosaur coloration is far broader than the feathered species that have so far dominated research. Even with limited samples, the discovery hints at biological diversity within a group long assumed to be visually uniform.

The work does not complete the picture, but it sharpens its edges. In doing so, it reminds us that ancient life was not static or simple, but dynamic and unexpectedly intricate. Each new clue—from a cluster of microscopic pigments to a pattern preserved in stone—brings us a step closer to understanding a world that vanished millions of years ago, yet continues to shape our imaginations today.

More information: Tess Gallagher et al, Fossilized melanosomes reveal colour patterning of a sauropod dinosaur, Royal Society Open Science (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsos.251232. royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.251232