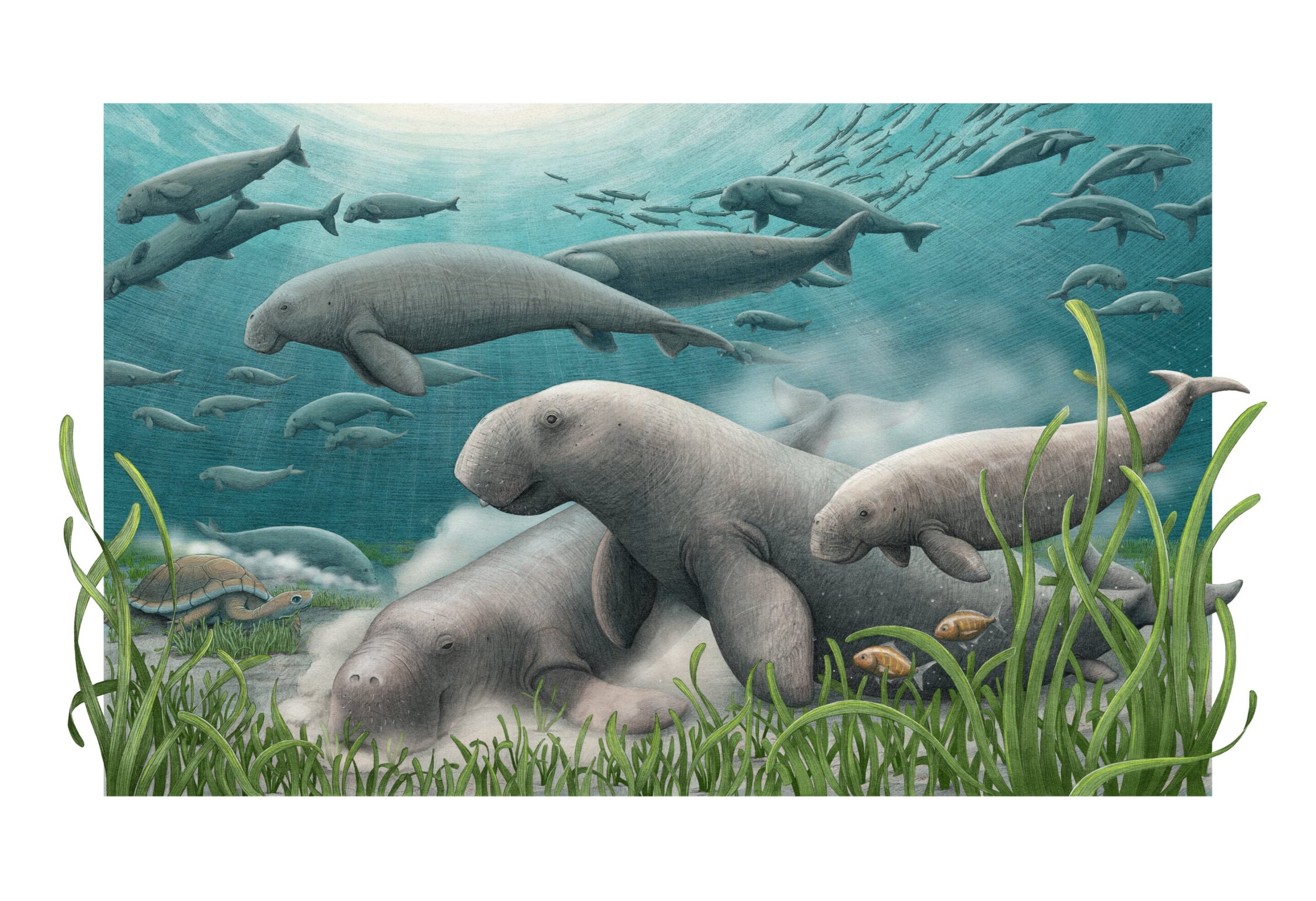

Imagine walking along the shallow waters of the Arabian Gulf, where the sun glimmers across endless seagrass meadows. Today, these waters are home to dugongs, graceful marine mammals often called sea cows, whose gentle grazing shapes the seafloor and nurtures a vibrant underwater world. Now, picture a journey 21 million years into the past, to a time when distant relatives of these creatures roamed the same waters, performing the same vital ecological roles long before humans ever set eyes on them.

That vision is no longer just imagination. A team of researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, in collaboration with Qatar Museums, has unveiled a remarkable fossil site in Qatar that sheds light on these ancient ocean gardeners. Their study, published in PeerJ, describes a new species of sea cow, Salwasiren qatarensis, and confirms that the Gulf has been a prime habitat for sea cows for more than 21 million years.

“We discovered a distant relative of dugongs in rocks less than 10 miles away from a bay with seagrass meadows that make up their prime habitat today,” said Nicholas Pyenson, curator of fossil marine mammals at the National Museum of Natural History. “This part of the world has been prime sea cow habitat for the past 21 million years—it’s just that the sea cow role has been occupied by different species over time.”

Unearthing a Dugong Cemetery

The story of Salwasiren qatarensis begins in the desert of southwestern Qatar at a site called Al Maszhabiya. Here, fossil hunters found a staggering treasure trove of sea cow remains. The area was first noted by geologists in the 1970s, who mistook the scattered bones for reptiles, but paleontologists returned decades later to reveal the true occupants: ancient sea cows.

“The area was called ‘dugong cemetery’ among the members of our authority,” said Ferhan Sakal, an archaeologist and head of excavation and site management at Qatar Museums. “But at the time, we had no idea just how rich and vast the bonebed actually was.”

In 2023, Pyenson, Sakal, and their colleagues conducted a detailed survey of the fossils. They identified more than 170 different locations containing sea cow remains, dating back to the Early Miocene epoch, roughly 21 million years ago. The richness of this bonebed rivals some of the most famous marine mammal fossil sites in the world, including Cerro Ballena in Chile, a graveyard of ancient whales.

The fossil record from Al Maszhabiya paints a vivid picture of a thriving shallow marine ecosystem. Sharks and barracuda-like fish patrolled the waters, dolphins swam alongside sea turtles, and amidst them grazed these ancient sea cows, shaping their environment in ways that echo the ecological influence of today’s dugongs.

A Miniature Marvel of the Miocene

Salwasiren qatarensis stood out among its peers. With an estimated weight of 250 pounds, it was small for a sea cow—comparable to an adult panda or a heavyweight boxer—but it still played a crucial role in the ecosystem. Unlike modern dugongs and manatees, these prehistoric sea cows retained hind limb bones and had straighter snouts and smaller tusks.

“It seemed only fitting to use the country’s name for the species as it clearly points to where the fossils were discovered,” Sakal said. The genus name, Salwasiren, honors the nearby Bay of Salwa, while the species name, qatarensis, directly acknowledges Qatar as the site of discovery.

The fossils suggest that Salwasiren and its contemporaries were not just passive inhabitants of the Gulf. The density of the bonebed indicates that these miniature sea cows actively shaped the seagrass meadows, stirring the sediment and releasing nutrients, much like modern dugongs do today. Pyenson explained, “The density of the Al Maszhabiya bonebed gives us a big clue that Salwasiren played the role of a seagrass ecosystem engineer in the Early Miocene the way that dugongs do today. There’s been a full replacement of the evolutionary actors but not their ecological roles.”

Lessons Hidden in Stone

The story of Salwasiren qatarensis is not just about uncovering ancient bones; it is a story about survival and resilience. Today, dugongs in the Gulf face mounting pressures from accidental fishing, pollution, rising temperatures, and increasing salinity. The seagrass meadows they depend on are changing faster than ever.

“If we can learn from past records how the seagrass communities survived climate stress or other major disturbances like sea-level changes and salinity shifts, we might set goals for a better future of the Arabian Gulf,” Sakal said. The fossils serve as a reminder that ecological roles can persist even as species come and go, offering insights into how modern conservation strategies might support these fragile marine ecosystems.

Preserving Heritage and the Future

The discovery also emphasizes the deep connection between culture, heritage, and natural history. Faisal Al Naimi, director of the Archaeology Department at Qatar Museums, reflected, “Dugongs are an integral part of our heritage, not only as a living presence in our waters today, but also in the archaeological record that connects us to generations past. The findings at Al Maszhabiya remind us that this heritage is not confined to memory or tradition alone, but extends deep into geologic time, reinforcing the timeless relationship between our people and the natural world.”

The research team has taken steps to digitally preserve their findings. Fossil skulls, vertebrae, and teeth from Salwasiren have been scanned and made accessible through the Smithsonian Voyager platform, allowing the public to explore 3D models and interactive educational experiences.

“The most important part of our collaboration is ensuring that we provide the best possible protection and management for these sites, so we can preserve them for future generations,” Sakal said. Plans are underway to nominate Al Maszhabiya for UNESCO World Heritage status, protecting this window into the past while inspiring future discoveries.

A Timeless Connection to the Sea

The story of Salwasiren qatarensis brings to life a Gulf long before human footprints touched its shores. It reveals how sea cows, small but powerful, shaped the rhythms of the ocean and nurtured the meadows that sustain life. The fossils are not just remnants of the past; they are guides for the present and future, showing that ecosystems and the creatures that engineer them endure through time.

By uncovering the delicate balance between ancient sea cows and their environment, researchers offer hope that lessons from the past can inform the Gulf’s future. In preserving the heritage of dugongs, both living and extinct, Qatar safeguards a narrative that stretches across millions of years, connecting humans to the deep, enduring pulse of the sea.

This research matters because it illuminates the resilience of life and the persistent roles of key species, offering a blueprint for conservation and a reminder that the natural world is both fragile and enduring. The past, etched in stone and bone, teaches us that safeguarding biodiversity is not just a scientific mission—it is a story of identity, survival, and our timeless connection to the sea.

More information: High abundance of Early Miocene sea cows from Qatar shows repeated evolution of seagrass ecosystem engineers in Eastern Tethys, PeerJ (2025). DOI: 10.7717/peerj.20030