For centuries, the Stone of Scone—also known as the Stone of Destiny—has been one of the most powerful symbols in the history of Great Britain. This 152-kilogram sandstone block, weathered and unassuming to look at, has carried the weight of crowns, nations, and centuries of rivalry between Scotland and England.

Every British monarch since the Middle Ages has been crowned above it. Yet, beneath the grandeur of royal ceremonies lies a story not only of power and tradition but of theft, rebellion, identity, and the quiet persistence of a nation’s pride.

Now, thanks to years of painstaking research by Professor Sally Foster of the University of Stirling, the fractured story of this sacred stone—and its literal fragments—is being pieced back together. Her study, recently published in The Antiquaries Journal, reveals the Stone’s remarkable journey through history, myth, and politics. It is a tale that reminds us how even a simple rock can become the beating heart of a nation’s soul.

A Stone Born of Myth and Power

The Stone of Scone’s origins are shrouded in mystery. It is believed to have been quarried somewhere near Perth, Scotland, though no one knows precisely when. What is certain is that by the 13th century, it had already become a symbol of Scottish sovereignty. Kings of Scotland were crowned upon it, believing the Stone held divine legitimacy.

To the Scots, it was not just a stone—it was destiny itself.

But destiny, as history often shows, can be stolen.

In 1296, during the Wars of Scottish Independence, England’s King Edward I invaded Scotland and seized the Stone, taking it to Westminster Abbey in London. There, it was fitted into the base of a wooden coronation chair, ensuring that every future English monarch—and later, every British monarch—would be crowned above the conquered symbol of Scotland’s kingship.

To the English, it became part of royal tradition. To the Scots, it was an open wound—a reminder of subjugation, of what had been taken and never returned.

A Daring Christmas Heist

Centuries passed. Empires rose and fell. Yet the Stone remained in London—until one cold Christmas morning in 1950, when four Scottish students decided to change history.

Led by 25-year-old law student Ian Hamilton, members of the Scottish Nationalist Party broke into Westminster Abbey with a bold plan: to take back the Stone of Destiny and return it to Scotland.

Their mission was fueled by patriotism and youthful audacity. But things did not go smoothly. As they struggled to lift the 152-kilogram stone from its ancient setting, it slipped and cracked in two. Still, they managed to load the pieces into their car and drive north, leaving behind the Abbey—and a furious British government.

For weeks, the story dominated headlines. Scotland was electrified. London was outraged. Some saw the students as heroes, others as vandals.

Eventually, the Stone was found three months later, repaired, and quietly returned to Westminster Abbey. But the symbolic damage was done. The Stone was no longer merely an artifact—it was a national icon reborn in the fires of rebellion.

The Man Behind the Replica

At the heart of this extraordinary saga was another figure: Robert “Bertie” Gray.

Gray was a Glasgow politician, magistrate, and monumental sculptor—a man of deep nationalist conviction and a leading member of the Scottish Covenant Association, which fought for self-government in Scotland. In the 1930s, years before the famous theft, Gray had created a replica of the Stone and dreamed of replacing the original in Westminster with his copy.

His plan was bold, almost mischievous—a symbolic act of resistance that would leave the English with a fake and return the real Stone to Scottish soil. Although his scheme never came to fruition, his involvement with the Stone would soon become legendary.

When the 1950 heist took place, Gray helped repair the broken artifact. In doing so, he kept a number of small stone fragments as souvenirs—a decision that would scatter pieces of the Stone of Destiny across the world.

The Scattered Fragments of Destiny

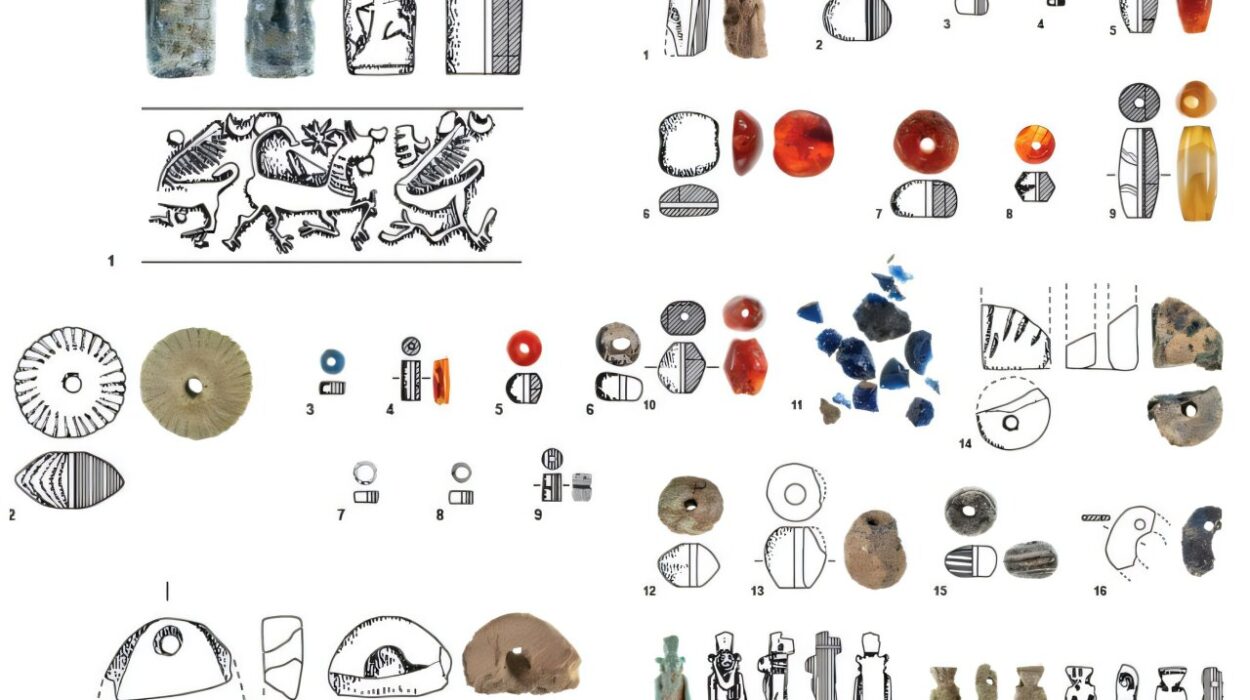

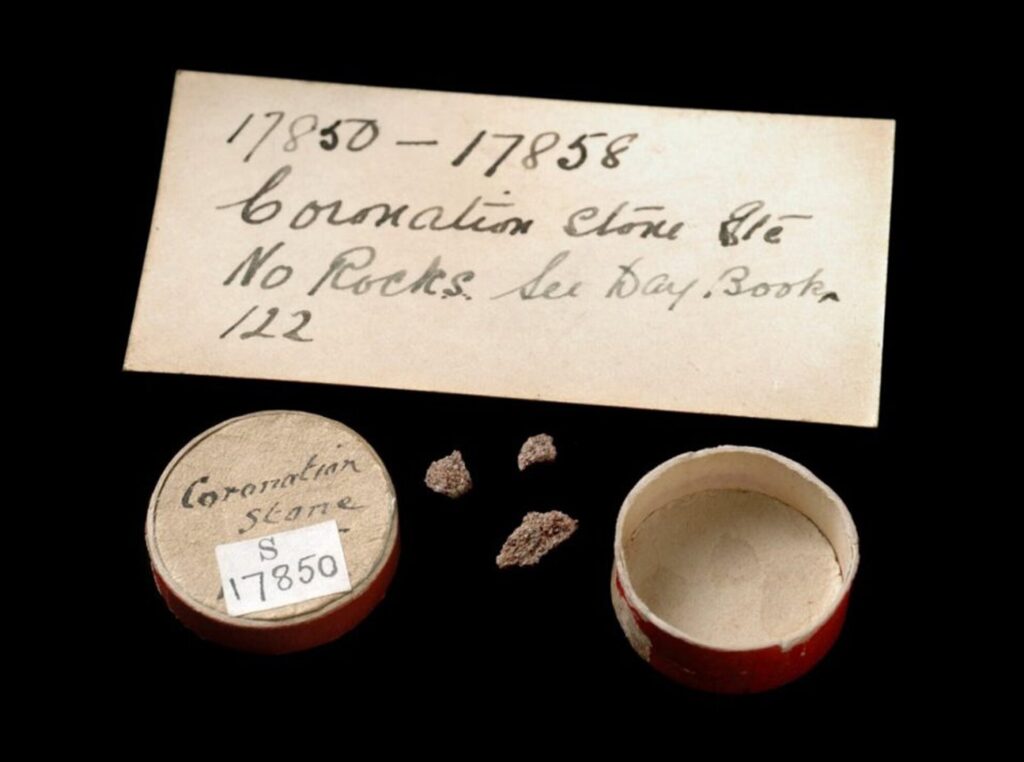

According to a 1956 newspaper report, there were 34 missing pieces of the Stone after its repair. These fragments—some tiny, others large enough to hold—were quietly given away by Gray, often accompanied by certificates of authenticity.

Professor Sally Foster has spent years tracking down these pieces, interviewing families, examining archives, and following faint paper trails across continents. Her research uncovered the current whereabouts of 17 of the fragments—each carrying its own remarkable story.

Some fragments were turned into jewelry. Ian Hamilton’s girlfriend received a brooch containing a piece of the Stone, while Scottish politician Winnie Ewing famously wore a locket with one inside. Ewing once joked, “I would like to be arrested for being in possession of stolen property.”

Other fragments were sent for scientific testing, and one found an unlikely home in Australia. During a visit to Scotland in the 1950s, an Australian woman met Bertie Gray and was gifted a fragment along with a letter of authentication. After her death, the piece was donated to the Queensland Museum in 1967—an unexpected corner of the British Empire now connected forever to Scotland’s national relic.

Each fragment carries its own micro-history, connecting individual families, communities, and even distant countries to the saga of the Stone.

The Stone Comes Home

After the 1950 theft, the Stone continued its role in royal coronations, but the calls for its return to Scotland grew louder. Finally, in 1996—700 years after it was first taken by Edward I—the British government agreed to return the Stone of Destiny to Scottish soil.

Tens of thousands gathered in Edinburgh to witness its arrival. The Stone was placed on display in Edinburgh Castle, near Scotland’s crown jewels, as a powerful symbol of national pride and cultural identity.

In 2024, it was moved again—this time to the new Perth Museum, close to where it was originally quarried, bringing its journey full circle.

Yet the Stone remains a shared symbol. It is still brought to Westminster for coronations, a reminder that history, like the stone itself, is both divided and bound together.

Piecing Together the Past

Professor Foster’s research goes beyond archaeology—it touches on memory, politics, and belonging. She describes her work as a “composite biography” of the Stone: not just a study of its physical form, but of the lives and meanings that have grown around it.

The scattered fragments, she argues, give the Stone new life. They link ordinary people to the grand narratives of history. A fragment in a locket, a chip preserved in a museum, a small piece lost in a drawer—each adds a new layer of significance.

“The fragmentation,” Foster writes, “has ultimately led to more personal connections for various families and significance of the stone to places outside of Great Britain.”

Still, 17 pieces remain missing. Perhaps they sit forgotten in attics, hidden in jewelry boxes, or passed down as curious heirlooms. Foster hopes that renewed public interest will help recover more of them, completing the puzzle of the Stone of Destiny once and for all.

A Symbol That Endures

The story of the Stone of Scone is not just about kings and ceremonies. It is about identity, resilience, and the power of symbols to unite and divide.

This block of sandstone has witnessed centuries of conquest and rebellion, reverence and defiance. It has been stolen, broken, hidden, repaired, and returned—yet it endures.

Each fragment, each scar, each journey adds to its meaning. The Stone of Destiny may have been fractured, but in its breaking, it became something larger than itself—a story shared by many, a legacy carried in stone and spirit alike.

And perhaps that is its true destiny—not to sit untouched beneath a throne, but to live on through the countless hands, hearts, and histories that continue to claim it as their own.

More information: Sally Foster, Life In Pieces: Lessons in the value of fragments from the secret lives of the stone of scone/destiny, The Antiquaries Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017/s0003581525100231