For generations, archaeologists and art historians have viewed the palette of Europe’s Paleolithic artists as stark and limited—dominated almost entirely by the earthy tones of red ochre and the dark shades of charcoal black. Cave walls across France and Spain, etched and painted by ancient hands, reflect this restricted spectrum. Until now, blue was conspicuously absent, leading scholars to assume it was unknown or unvalued in the deep past.

But a recent discovery at the Final Paleolithic site of Mühlheim-Dietesheim in Germany has cracked open that assumption. On a humble stone artifact, researchers detected something that should not have been there: traces of a luminous blue mineral pigment known as azurite. At 13,000 years old, it is the earliest known use of blue pigment in Europe, a revelation that forces us to reconsider how early humans expressed creativity, identity, and meaning.

The Discovery of Azurite

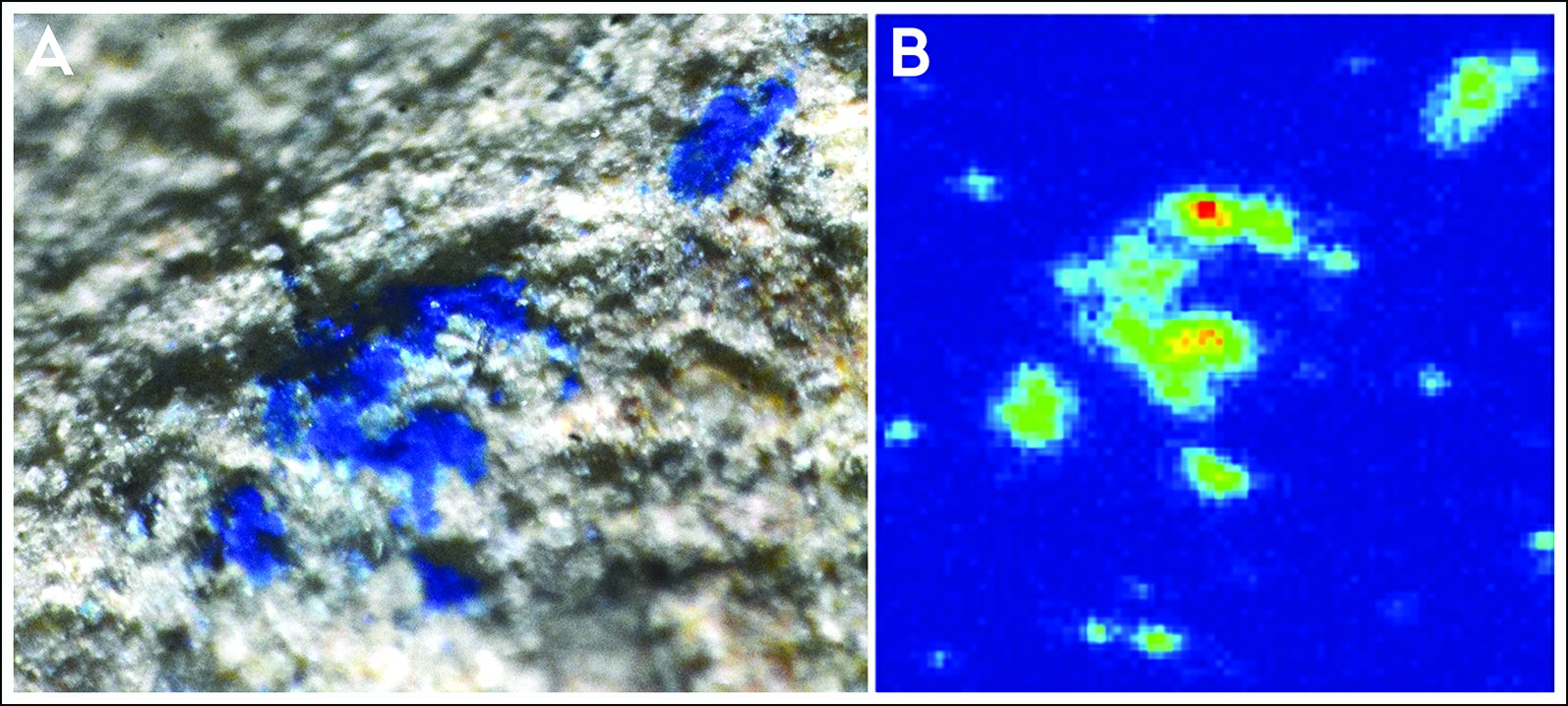

The finding began with an ordinary-looking stone, once believed to have functioned as a simple oil lamp. Upon closer inspection, however, scientists noticed faint residues of an unusual color clinging to its surface. What followed was a series of advanced analyses—spectroscopy, microscopy, and geochemical testing—that confirmed the presence of azurite, a copper-based mineral prized in later historical periods for its brilliant, sky-like hue.

This was no accidental stain of earth or contamination from the surrounding soil. The stone bore deliberate traces of pigment preparation. Rather than burning oil, it seems to have served as a mixing surface or palette, where powdery blue pigment was ground, prepared, or combined for use.

Rewriting the Story of Paleolithic Colors

Until this moment, the narrative of Paleolithic color use was relatively straightforward. Red and black pigments dominated because they were both abundant and enduring. Red ochre could be dug from iron-rich soils, and charcoal was easily obtained from fire. These colors appear everywhere in cave art, body painting residues, and ritual deposits.

Blue, however, was missing. Scholars long argued that the absence reflected either the scarcity of blue minerals or their lack of symbolic appeal. But the traces of azurite in Germany tell a different story. Paleolithic communities not only knew of blue minerals, they actively collected, processed, and applied them. The fact that azurite does not survive well on stone surfaces may explain why we had not noticed it before—its uses may have been confined to bodies, textiles, or objects now lost to time.

Beyond the Cave Walls

If the blue pigment was not applied to cave walls, then where did it go? Archaeologists now speculate that it may have been used in ways that rarely leave behind durable traces. It could have been smeared on skin, woven into fabric, or painted onto wooden objects or animal hides. Perhaps it played a role in rituals, ceremonies, or expressions of status and identity.

To decorate the body in shimmering blue, or to wear dyed garments that stood apart from the ordinary earth tones of the Paleolithic landscape, would have been a striking visual statement. It may have carried symbolic power, evoking the sky, water, or the spiritual realm. Blue, in many later cultures, became a color of rarity and prestige—this discovery hints that its allure may stretch far deeper into prehistory than we realized.

A Sophisticated Knowledge of Materials

What makes this discovery so remarkable is not just the pigment itself but what it reveals about the people who used it. To obtain azurite, early humans would have needed to recognize the mineral in the environment, extract it, and grind it into usable powder. This required both geological awareness and technical skill.

It also suggests a level of selectivity in color choice. If red and black pigments were readily available, the effort to acquire blue must have carried special meaning. These were not people limited by ignorance or necessity. They were making conscious aesthetic and symbolic decisions, choosing colors to communicate messages we may never fully decode.

Rethinking Creativity in the Paleolithic

The presence of azurite on this artifact invites us to see Paleolithic communities in a new light. They were not simply painting animals on cave walls for survival rituals; they were experimenting with color, playing with beauty, and expressing complex identities. Their art and decoration may have been more vibrant, diverse, and imaginative than the archaeological record currently shows.

As Dr. Izzy Wisher of Aarhus University, the study’s lead author, explains, “The presence of azurite shows that Paleolithic people had a deep knowledge of mineral pigments and could access a much broader color palette than we previously thought.” Their creativity extended far beyond the red and black images we see preserved on stone. Much of it may have vanished with perishable materials—but discoveries like this remind us that art has always been more expansive than what survives.

The Broader Implications

The discovery at Mühlheim-Dietesheim does more than add a new color to the Paleolithic palette. It redefines our understanding of how early humans engaged with their world. Colors were not just aesthetic choices—they carried meaning, emotion, and power. The use of blue may have been tied to social status, ritual life, or symbolic associations we cannot yet trace.

It also demonstrates that the origins of artistic experimentation reach further back than previously imagined. Long before written language or organized states, people were already manipulating the materials of the earth to create beauty and symbolism. Art, in this sense, is not a luxury of civilization but a fundamental expression of humanity itself.

A Glimpse into Human Spirit

Standing at the threshold of this discovery, we are reminded that the urge to color the world is as old as our species. The first humans who ground azurite into powder were not only experimenting with minerals—they were painting their lives with imagination. Perhaps they decorated their bodies before a dance, or dyed fabrics that fluttered against the pale winter landscape. Perhaps the shimmer of blue in firelight carried meanings of hope, transcendence, or connection to the sky above.

Thirteen thousand years later, that faint trace of color survives as a whisper across time. It tells us that humans have always sought to push beyond the ordinary, to seek beauty even in hardship, and to use creativity as a way of making sense of existence.

Toward a Fuller Picture of the Past

The discovery of Europe’s earliest blue pigment is more than an archaeological finding—it is a reminder that our ancestors were not primitive caricatures, but inventive, observant, and profoundly human. They recognized the power of color, experimented with its possibilities, and infused their lives with meaning through creative acts.

As researchers continue to analyze pigments, tools, and artifacts from prehistory, we may uncover more evidence of colors and practices that have been hidden by time. Each discovery expands the canvas of human history, showing us that even at the dawn of culture, people were already painting with imagination, crafting with intention, and dreaming in vibrant hues.

The stone at Mühlheim-Dietesheim does not simply bear pigment—it bears witness to the enduring human drive to transform the world into art.

More information: Izzy Wisher et al, The earliest evidence of blue pigment use in Europe, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.10184