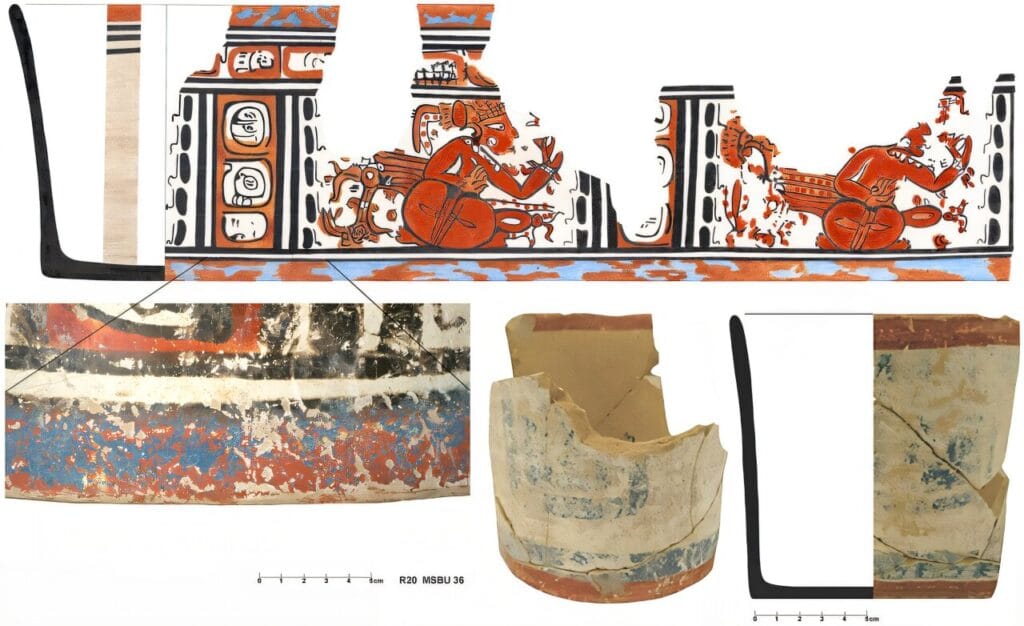

Under the sweltering tropical sun of Belize, archaeologists unearthed pottery sherds painted in a vivid, almost otherworldly blue. Despite the passage of over a thousand years, the color hadn’t faded. It was Maya Blue—a pigment so durable that it has survived sunlight, humidity, and even acid for centuries.

In a new study published in Ancient Mesoamerica, Dr. Dean Arnold and his colleagues Joseph Ball, Laure Dussubieux, and Jennifer Tachek analyzed 17 samples of this remarkable pigment from the Late-Terminal Classic Period (AD 680–860) at Buenavista del Cayo, Belize. Their findings shed light not only on the pigment’s composition but also on the sophisticated networks of trade, ritual, and knowledge that allowed this sacred color to flourish in Maya civilization.

Unlocking an Ancient Formula

Maya Blue was unlike anything else in the ancient world. Created by combining organic indigo dye with inorganic palygorskite clay, it resisted the natural fading that plagued other pigments. While pure indigo would have washed away in sunlight or degraded in acid rain, Maya Blue remained stubbornly vibrant—a chemical miracle that puzzled scientists for centuries.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that researchers discovered its composition. Even then, the method of its creation remained elusive. Later studies revealed tantalizing clues: at the base of an offering vessel found at Chichén Itzá, traces of indigo, Maya Blue, palygorskite, and melted copal incense were found together. This led scholars to theorize that Maya Blue was likely crafted during ritual burnings, where the heat of copal resin fused the dye and clay into a stable, enduring pigment.

A Sacred Shade of Power

For the ancient Maya, blue was far more than a color—it was divine. It symbolized water, rain, sacrifice, and fertility, concepts essential for survival in a tropical environment where agriculture depended heavily on rainfall. Sixteenth-century priest Fray Diego de Landa recorded that sacrificial altars and even victims themselves were painted blue before rituals, underscoring its spiritual significance.

This wasn’t a pigment anyone could make. Joseph Ball explains that crafting Maya Blue likely required specialized, even secret, knowledge:

“Such artisans were most likely sub-royal members of the royal court, possibly even non-regent members of the royal family itself. The color blue was sacred to the Maya, and its manufacture involved esoteric knowledge not widely shared or available.”

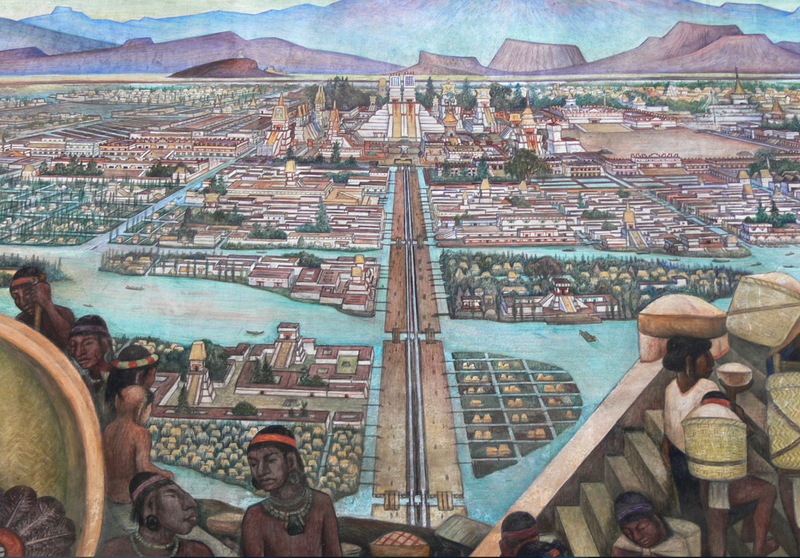

In the city of Buenavista-Komkom—an ancient name now preserved in modern Guatemalan orthography—this sacred color was closely tied to the rain god Chaac, believed to be the city’s patron deity. Chaac’s favor meant life-giving rains, fertile fields, and survival for the community, making the pigment not just decorative but a spiritual necessity.

Tracing the Origins of a Precious Clay

While scientists have long known how Maya Blue was made, its raw materials, especially palygorskite, raised lingering questions. Was this clay mined locally near Buenavista, or did it travel great distances across the Maya world?

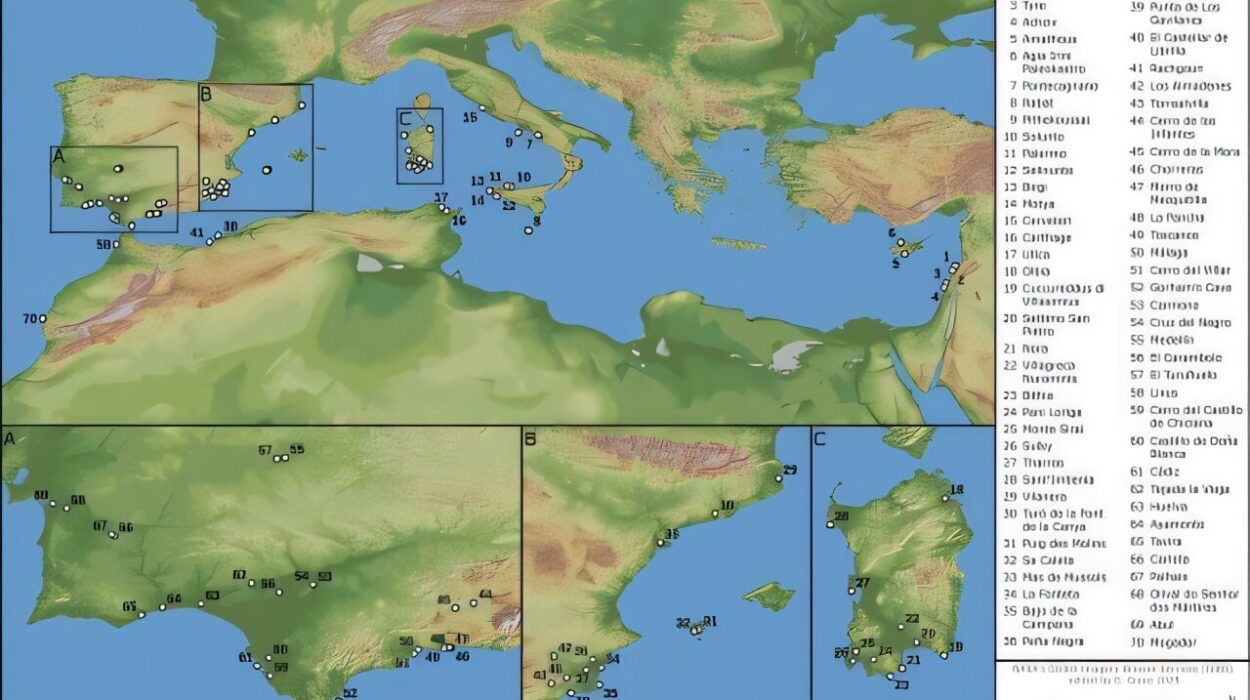

To solve the mystery, Dr. Arnold’s team analyzed palygorskite samples from Buenavista’s ceremonial pottery. Using advanced compositional techniques, they discovered that the clay originated from Sacalum—a site over 375 kilometers away. This revelation painted a vivid picture of ancient Maya trade: pigment materials, or perhaps already-prepared Maya Blue, journeyed across hundreds of kilometers to reach even medium-sized inland cities like Buenavista.

Canoes on Sacred Waters

How did this sacred pigment travel so far? While overland paths connected Maya cities, they were fraught with danger. The Late Classic period was a time of constant warfare; carrying valuable cargoes through hostile territories would have been perilous.

Joseph Ball explains that maritime routes offered a safer, faster alternative:

“Maritime routes along the north-central Yucatan coast or from northeastern Quintana Roo to the Belize River mouth were likely the main arteries. From there, canoers could travel upstream to Buenavista. Coastal sea routes were not only more efficient but also safer than overland routes, where merchants risked hostile encounters.”

Evidence suggests that Maya traders mastered seafaring to a remarkable degree. Christopher Columbus himself encountered a massive 50-foot Maya trading canoe off Cuba during his first voyage, a testament to their navigational prowess. These maritime highways likely carried not just goods but ideas and sacred knowledge, including the tightly guarded secrets of Maya Blue’s creation.

Why Buenavista?

One of the study’s intriguing puzzles is why a relatively modest center like Buenavista had such abundant access to a pigment so precious and esoteric. In Maya society, prestige goods often flowed toward large, dominant city-states. Yet Buenavista’s elite clearly had connections—or influence—that allowed them to acquire large quantities of this sacred pigment from distant mines.

Future research will explore whether Buenavista’s rulers maintained exclusive trade alliances, participated in religious networks that granted them access to Maya Blue, or perhaps held specialized ritual knowledge that elevated their importance despite their city’s size.

The Legacy of Maya Blue

What emerges from this research is more than a technical account of pigment production. It is a story of culture, spirituality, and resilience. Maya Blue links artisans to kings, rituals to rain gods, and distant mines to riverside courts. It tells of a civilization that wove together art, religion, and long-distance trade into a vibrant tapestry of meaning.

Despite centuries of tropical rains and relentless sunlight, Maya Blue still shines brightly on ancient pottery and temple walls. It stands as a physical echo of Maya ingenuity—a color born of fire and ritual, carried by canoes over vast waters, protected by artisans who understood that certain secrets were meant to endure.

Today, as scientists like Dr. Arnold and his colleagues peel back the layers of this pigment’s past, they not only solve archaeological mysteries but also reconnect us to the spiritual world of the Maya, where a single shade of blue carried the weight of gods, rain, and life itself.

Reference: Dean E. Arnold et al, Palygorskite from Sacalum, Yucatán in Maya Blue From the Eastern Maya Lowlands: New Evidence From Buenavista Del Cayo, Belize and La-ICP-MS Analysis, Ancient Mesoamerica (2025). DOI: 10.1017/S0956536125000082