At first glance, the Gray Fossil Site in northeastern Tennessee seems like a portal into a strange, lost world — a place where ancient tapirs roamed alongside rhinos, mastodons, and saber-toothed cats. But among these exotic relics, researchers have uncovered something surprisingly familiar: the delicate remains of a deer.

This is no ordinary deer. The 5-million-year-old fossils, described in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica, belong to Eocoileus gentryorum — one of the earliest members of the deer family ever found in North America. It’s a discovery that links the forests of the distant past to the landscapes we know today, revealing the likely ancestor of the white-tailed deer that still wander Appalachian woodlands.

“The Gray Fossil Site continues to yield extraordinary discoveries that reshape our understanding of ancient life,” said Dr. Blaine Schubert, executive director of the Gray Fossil Site and Museum. “From tapirs and mastodons to these early deer, we’re revealing the incredible diversity of life that once flourished in Tennessee and how some species, like deer, have shown amazing resilience through geological time.”

Reconstructing a 5-Million-Year-Old Life

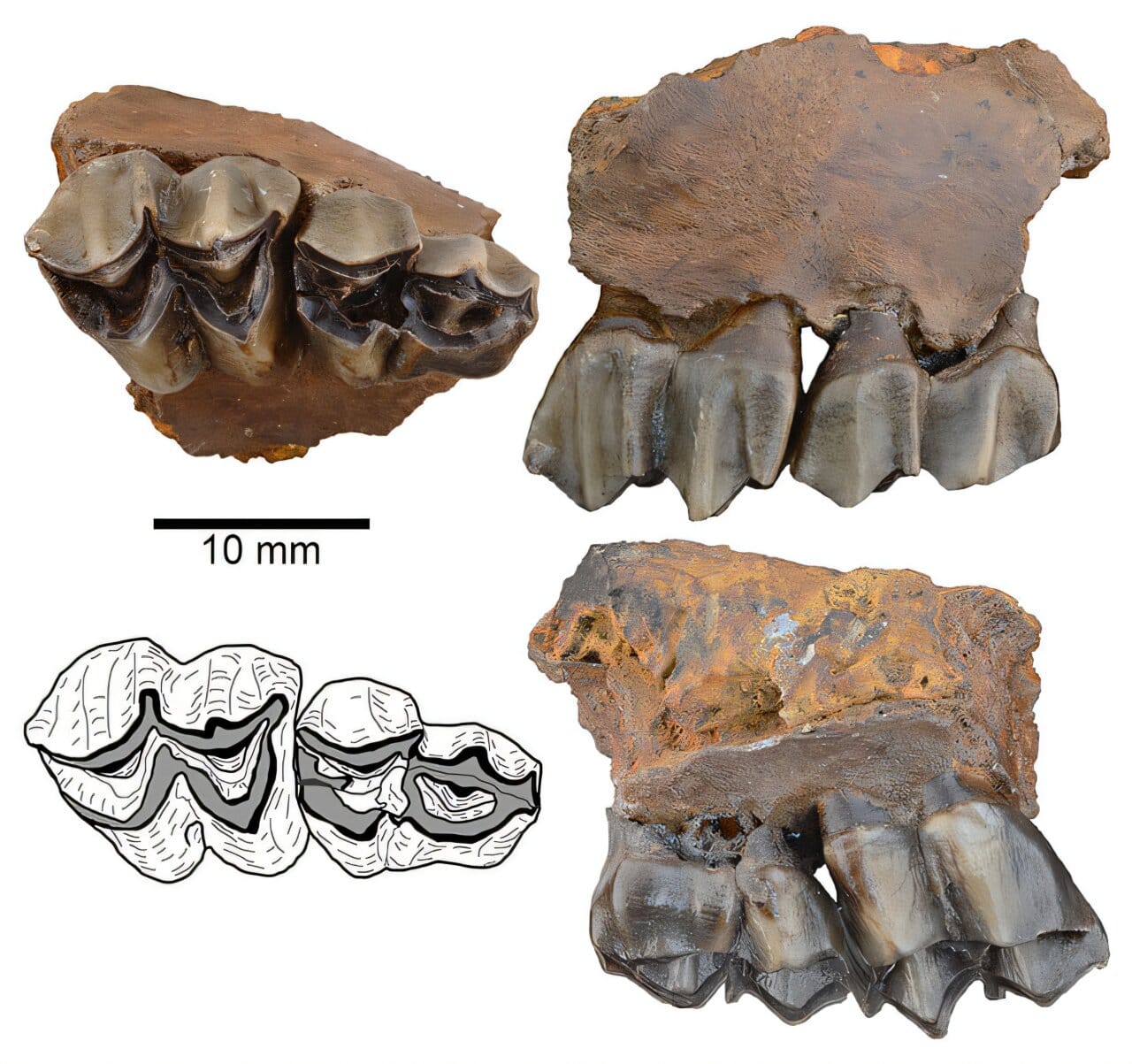

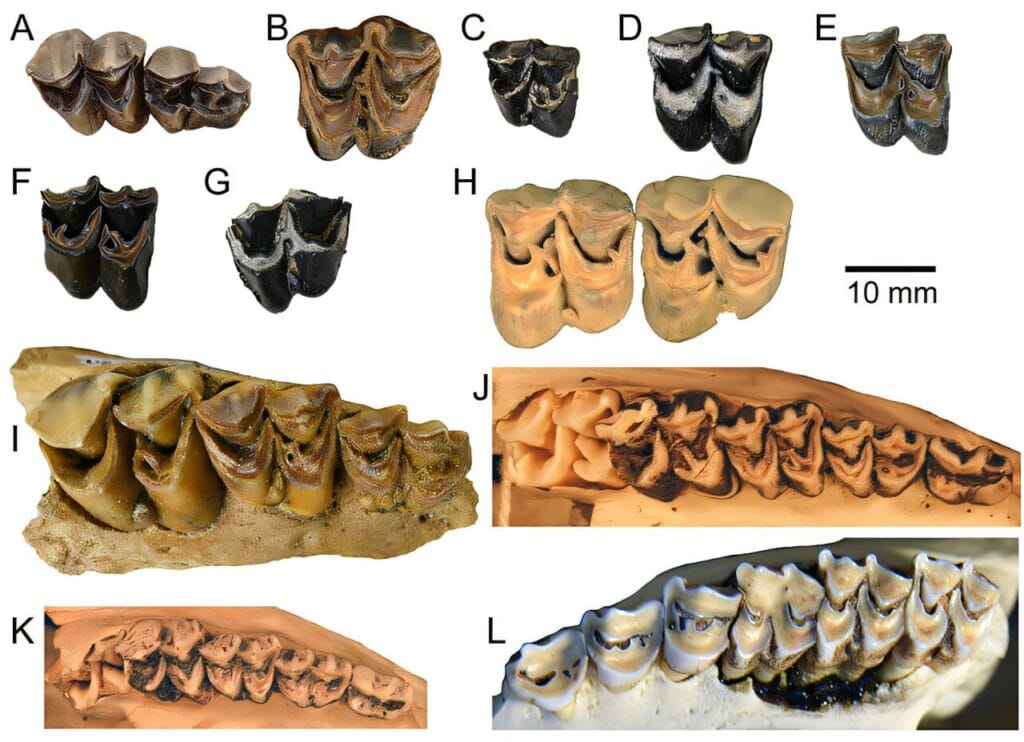

The research team — led by Head Curator Dr. Joshua Samuels, recent graduate Olivia Williams, and Assistant Collections Manager Shay Maden — pieced together the animal’s story from a handful of clues: part of a juvenile skull, an upper molar, and various limb bones.

Until now, Eocoileus gentryorum had been known only from fossils in Florida. Finding it in Tennessee not only extends its known range but also hints at how swiftly these early deer spread across North America after their arrival.

“These early deer are generally smaller than modern deer species in the New World,” Williams explained. “The only smaller species today are the Key deer of Florida and the brocket deer of Central and South America.”

The smaller size may have helped these early deer thrive in dense forests, weaving quietly through the undergrowth of prehistoric Appalachia.

Survivors of Dramatic Change

Fossil evidence from Washington state and Florida suggests that once deer reached North America, they spread rapidly from coast to coast. They adapted to habitats ranging from Pacific rainforests to Appalachian highlands — a flexibility that would prove essential for surviving millions of years of climate change.

“Deer have probably filled the same ecological role in Appalachian forests for nearly 5 million years,” Samuels noted. “They’ve persisted through dramatic climate shifts and habitat changes that wiped out many other large herbivores.”

This resilience is striking when compared to other ancient Gray Fossil Site inhabitants — many of which vanished entirely as the Ice Ages transformed the continent. Deer, however, endured and evolved, eventually giving rise to the white-tailed deer that now roam across much of the United States.

Connecting Appalachia’s Past and Present

The discovery adds to a remarkable list of recent finds from the Gray Fossil Site, including a giant flying squirrel and a powerful-jawed salamander. Together, they form a vivid portrait of a prehistoric Appalachian ecosystem — one that feels both alien and strangely familiar.

“Discoveries like this connect Appalachia’s past to its present in powerful ways,” said Dr. Joe Bidwell, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at East Tennessee State University. “Our researchers are revealing not just the history of a species, but the evolutionary lineage of life in this region. It’s work that exemplifies ETSU’s commitment to exploring and preserving the natural history of Appalachia.”

For visitors to the Gray Fossil Site and Museum, it’s a humbling thought: the deer seen grazing at the forest’s edge today are part of a story that stretches back millions of years — a story written in bone, buried in the Appalachian soil, and brought to light by the careful hands of science.

More information: Joshua X. Samuels et al, Early Pliocene Deer from the Gray Fossil Site, Appalachian Highlands, Tennessee, USA, Palaeontologia Electronica (2025). DOI: 10.26879/1560