In the arid canyons and dusty outcrops of southern Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, fossil hunters have long been piecing together the story of life during the age of dinosaurs. For decades, these rocks have surrendered the bones of fearsome tyrannosaurs, horned ceratopsians, and strange duck-billed giants. But now, from the quiet recesses of a museum drawer, emerges a different kind of beast—one smaller, armored, and goblin-like.

Meet Bolg amondol, a newly described species of large-bodied lizard that prowled the subtropical floodplains of Late Cretaceous North America around 76 million years ago. Roughly the size of a raccoon and armed with bony skull armor, Bolg belonged to a mysterious group of lizards called monstersaurs—distant cousins of the venomous Gila monster that still inhabits deserts of the American Southwest.

It’s not just the creature’s fearsome appearance or mythic name that’s turning heads in the paleontological community. This discovery, published in Royal Society Open Science, reveals a stunning and previously unrecognized diversity of large predatory lizards coexisting with dinosaurs—and it all started when a paleontologist opened a jar labeled “lizard.”

“I opened this jar of bones at the Natural History Museum of Utah and thought, ‘Oh wow, there’s a fragmentary skeleton here,’” said lead author Hank Woolley of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “I immediately knew it was something special.”

From Forgotten Bones to Fossil Fame

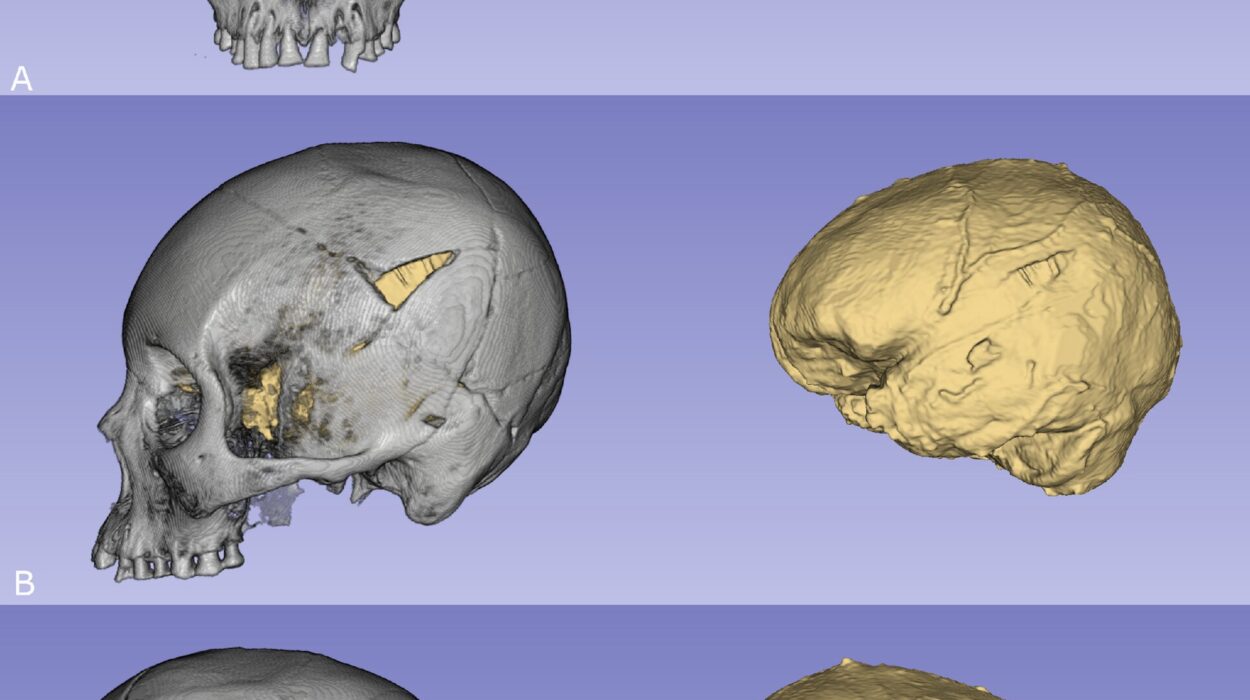

The fossilized remains of Bolg had been resting quietly for years in the museum’s collections, unstudied since their discovery in 2005. But it took Woolley, a specialist in lizard evolution, to recognize the hidden importance of the skeletal fragments—bits of skull, limbs, vertebrae, and a distinctive bony armor called osteoderms.

Though fragmentary, the remains are unusually complete for a fossil lizard from the Cretaceous. Most lizard fossils from this era consist of little more than a single jawbone or an isolated tooth. But Bolg offered up a partial skeleton, allowing scientists to piece together a more comprehensive view of its anatomy and evolutionary relationships.

That allowed researchers to place Bolg within the broader family tree of monstersaurs—a lineage characterized by spiny teeth, thick armor, and a long evolutionary history stretching back more than 100 million years.

“Having so many bones lets us test ideas about how these animals are related and where they might have lived or evolved,” Woolley said.

The Monstersaur’s Playground

Standing about three feet from snout to tail, Bolg would have been a formidable predator in its ecosystem—likely hunting eggs, small reptiles, mammals, and other vulnerable prey in the dense forests of ancient southern Utah. It was no dinosaur, but certainly no creature to trifle with either.

“If you encountered this lizard today, it would be about the size of a Savannah monitor—a large, aggressive lizard that you really don’t want to mess with,” Woolley added.

This predator wasn’t alone. Bolg is one of at least three large predatory lizards known from the Kaiparowits Formation, a fossil-rich stretch of rock that records a vibrant and dynamic Cretaceous ecosystem. This suggests that Late Cretaceous lizards were not merely scurrying background players in a dinosaur-dominated world, but thriving in ecological niches as mid-level predators.

“The fact that Bolg coexisted with several other large lizard species indicates a stable and productive ecosystem,” said Randy Irmis, a co-author on the study and curator of paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Utah. “These animals were taking advantage of diverse prey and a range of micro-habitats.”

A Name Worthy of Middle Earth

The goblin-like appearance of Bolg, especially its mound-like skull armor, inspired Woolley to look to fantasy for a fitting name. Drawing from J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium, the team named the lizard Bolg amondol—after Bolg, the goblin prince from The Hobbit. The species epithet, “amondol,” combines Tolkien’s Elvish words for “mound” and “head,” a nod to the armored knobs on the creature’s skull.

“Bolg just sounded right,” said Woolley. “It’s goblin-y, it’s tough, and it fits the look of the animal perfectly.”

But behind the whimsical name lies serious science. The discovery of Bolg sheds light on biogeographic connections between continents during the Late Cretaceous. Its closest known relative lived far away in the Gobi Desert of Asia, suggesting that lizards—like dinosaurs—were capable of migrating across continents when land bridges and changing sea levels made it possible.

“Smaller animals like lizards don’t always preserve well in the fossil record, so when we find a connection like this, it’s a big deal,” Irmis said. “It shows us that the evolutionary story of lizards is more complex—and more global—than we once thought.”

Treasures Hidden in Plain Sight

Bolg‘s discovery also underscores the critical role that natural history museums play in paleontology. Though the fossil was unearthed nearly two decades ago, it wasn’t until the right expert came along that its significance was recognized.

“Museum collections are full of untapped potential,” said Irmis. “Specimens can sit in drawers for years until someone with the right expertise takes a closer look. That’s why it’s so important to fund collections care and make these resources accessible.”

And it’s not just what’s in the drawers—it’s what still lies buried in the rock. The Kaiparowits Formation and the surrounding Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument have become a treasure trove of Cretaceous fossils, yielding everything from tiny mammals to towering dinosaurs to newly recognized lizard monsters.

Joe Sertich, a co-author from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Colorado State University, believes that these discoveries only scratch the surface.

“The record of big lizards from Grand Staircase-Escalante may actually be typical of dinosaur-era ecosystems,” he said. “They likely filled important roles as agile, egg-eating predators in the shadows of the giants.”

The Monster That Changed the Map

While Bolg won’t be starring in any blockbuster dino flicks, its discovery has reshaped how paleontologists view the diversity and dispersal of reptiles during the final chapters of the dinosaur age. It also serves as a reminder that the history of life on Earth is often told in fragments—fossils half-buried in stone, bones mislabeled in jars, or creatures hiding in plain sight, just waiting for the right eyes to see them.

“Finding Bolg shows how much we still have to learn,” Woolley said. “Every new discovery like this fills in part of the evolutionary puzzle—and reveals how strange, diverse, and dynamic life really was during the age of dinosaurs.”

And in that way, Bolg lives up to its goblin namesake: a small but mighty player in a world ruled by monsters.

Reference: New monstersaur specimens from the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah reveal unexpected richness of largebodied lizards in Late Cretaceous North America, Royal Society Open Science (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsos.250435