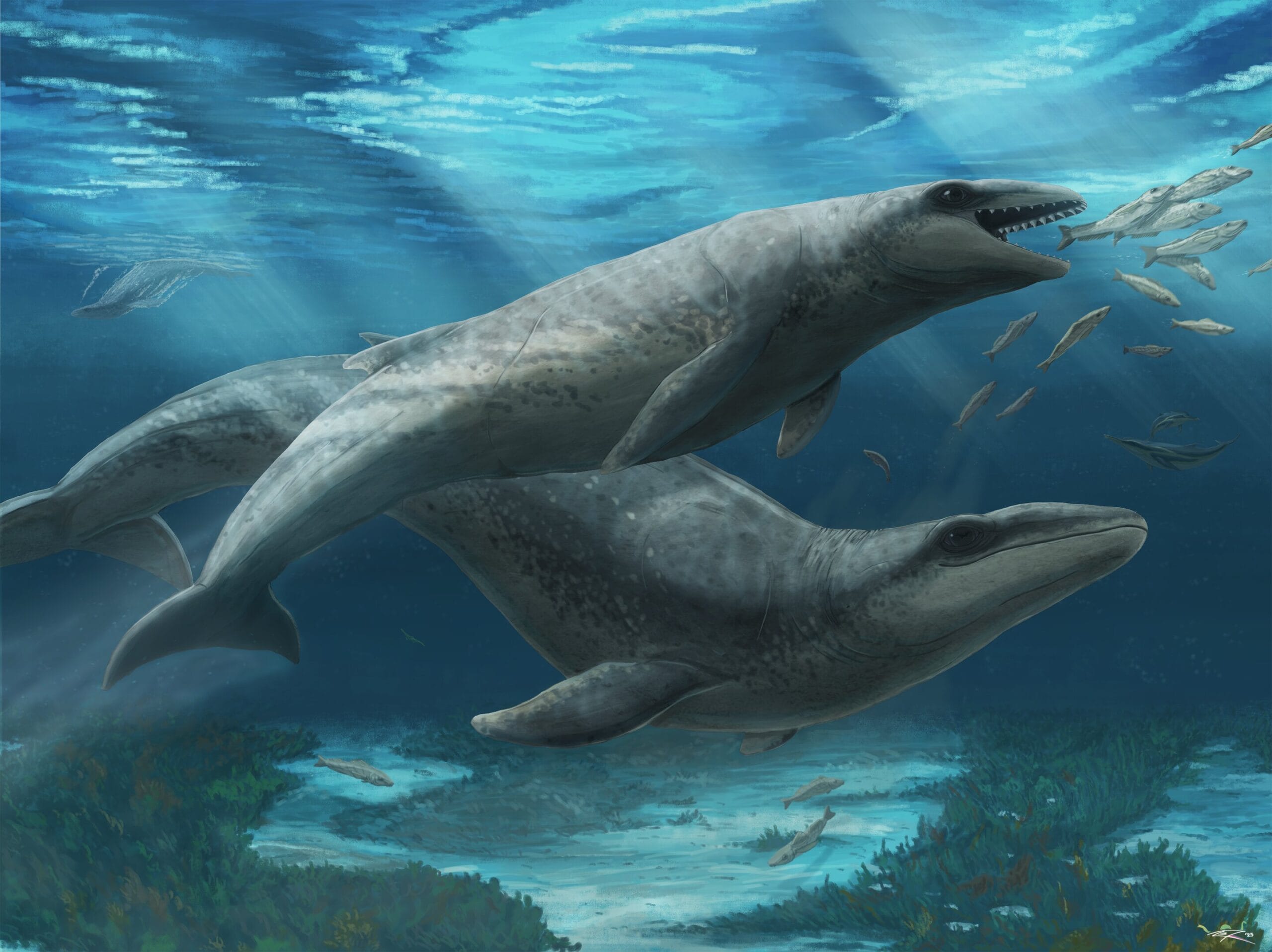

Long before the graceful, filter-feeding whales we know today roamed the seas, a very different kind of whale sliced through the waters off ancient Victoria. With enormous eyes, razor-sharp teeth, and a compact, muscular frame, Janjucetus dullardi was no oceanic giant—it was a swift, dolphin-sized predator built for the hunt.

The newly described fossil, unveiled by scientists from Museums Victoria’s Research Institute, has provided a rare and vivid glimpse into a pivotal stage of whale evolution. Dating back around 26 million years, it tells the story of a time when the ancestors of today’s baleen whales were still fierce hunters, armed with slicing teeth instead of filtering plates.

A Beach Walk Turns to a World-Class Discovery

The story began on a winter’s day in June 2019, when local resident Ross Dullard was strolling along the surf at Jan Juc, on Wadawurrung Country, Victoria’s Surf Coast. Amid the stones and shells, he spotted a fossilized fragment of bone.

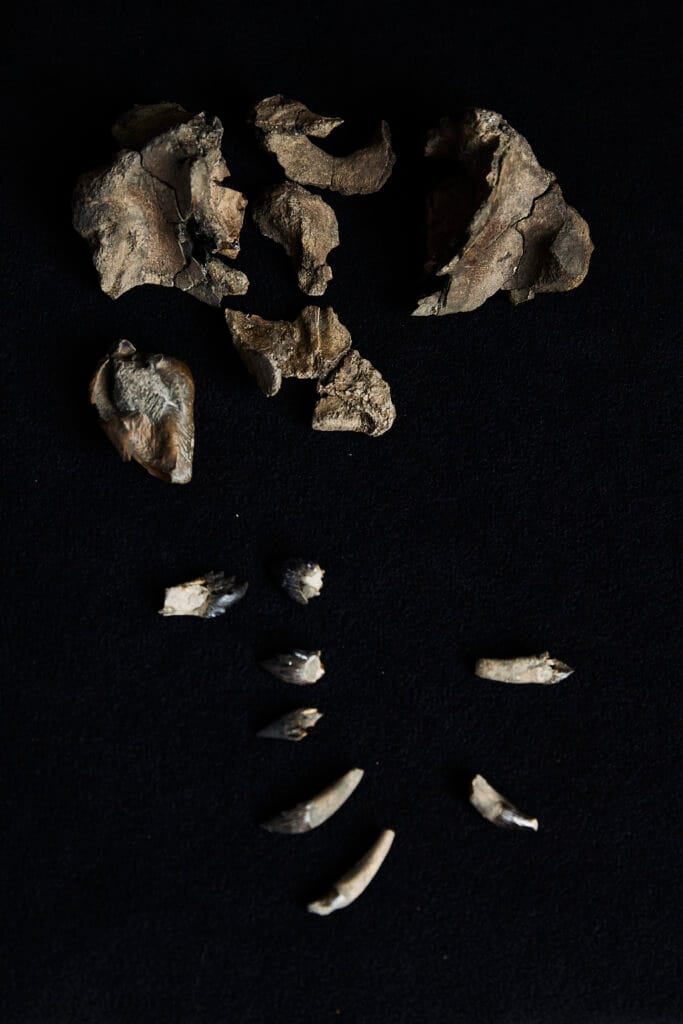

It turned out to be far more than a curiosity. Dullard’s find—a partial skull complete with ear bones and teeth—was a paleontological treasure. Recognizing its importance, he donated it to Museums Victoria. In honor of his contribution, the species now carries his name: Janjucetus dullardi.

“This kind of public discovery and its reporting to the museum is vital,” said Dr. Erich Fitzgerald, senior curator of vertebrate paleontology and senior author of the study. “Ross’ discovery has unlocked an entire chapter of whale evolution we’ve never seen before. It’s a reminder that world-changing fossils can be found in your own backyard.”

Small Body, Big Bite

Despite its modest size—just over two meters long—the juvenile Janjucetus dullardi was no timid swimmer. With forward-facing eyes for binocular vision, a short snout, and a mouth bristling with sharp teeth, it was a predator designed for quick, precise strikes.

“Think of it as the shark-like version of a baleen whale—small and deceptively cute, but definitely not harmless,” said lead author Ruairidh Duncan, a Ph.D. student at Museums Victoria Research Institute and Monash University.

The species belonged to a now-extinct group called mammalodontids, which lived exclusively during the Oligocene Epoch, roughly 30 to 23 million years ago. Mammalodontids are among the earliest known relatives of baleen whales, yet they still retained teeth and a predatory lifestyle.

A Global Rarity with Local Roots

Only four mammalodontid species are known worldwide, and this is the third found in Victoria. But Janjucetus dullardi stands out: it is the first fossil of its kind to preserve both teeth and inner ear bones in exceptional detail.

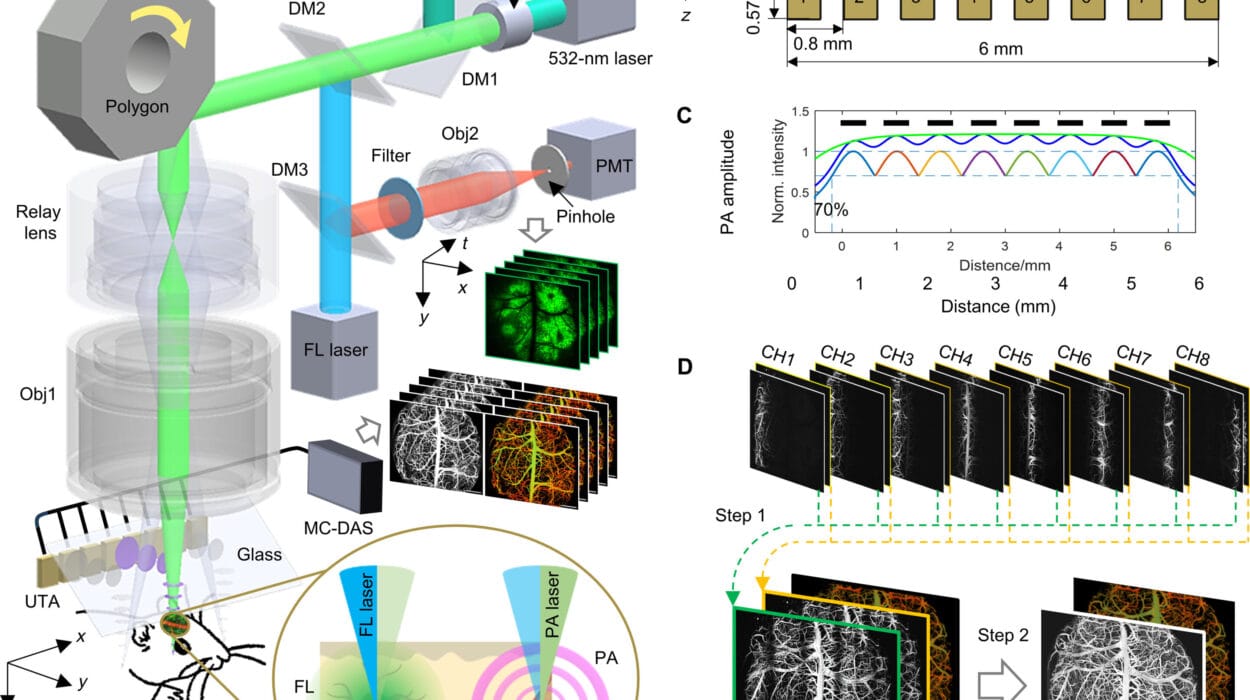

Using advanced microCT scanning, researchers peered inside the delicate ear structures, including the cochlea, which controls hearing sensitivity. This allowed scientists to reconstruct how the animal might have detected prey and navigated its underwater environment—an essential skill for a predator in murky coastal waters.

“This fossil opens a window into how ancient whales grew and changed, and how evolution shaped their bodies as they adapted to life in the sea,” Fitzgerald explained.

Ancient Seas and Climate Clues

The fossil came from the Jan Juc Formation, a layer of rock rich in marine fossils. Around 26 million years ago, this region was submerged under warm, shallow seas during a period of global warmth and rising sea levels.

Studying how early whales thrived in those ancient climates offers clues for how modern marine life might adapt—or struggle—in the face of current climate change.

“This region was once a cradle for some of the most unusual whales in history,” Fitzgerald said. “We’re only just beginning to uncover their stories.”

A New Chapter in Whale History

For paleontologists, Janjucetus dullardi represents more than just a new species. It fills a gap in the evolutionary puzzle, showing the transition from active, toothy hunters to the gentle, baleen-equipped giants we know today.

Lynley Crosswell, CEO and Director of Museums Victoria, said the discovery highlights the power of museum collections to transform our understanding of life on Earth.

“Thanks to the generosity of the public and the expertise of our scientists, Museums Victoria Research Institute is making globally significant contributions to evolutionary research. Discoveries like Janjucetus dullardi remind us that our collections are not just about the past—they’re shaping the future of science.”

As the coastline continues to yield its ancient secrets, researchers believe more groundbreaking finds lie ahead. For now, the fierce little whale from Jan Juc stands as a reminder that evolution’s path is rarely straight—and that even the mightiest giants began as hunters in the shallows.

More information: Ruairidh Duncan et al, An immature toothed mysticete from the Oligocene of Australia and insights into mammalodontid (Cetacea: Mysticeti) morphology, systematics and ontogeny, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2025). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf090