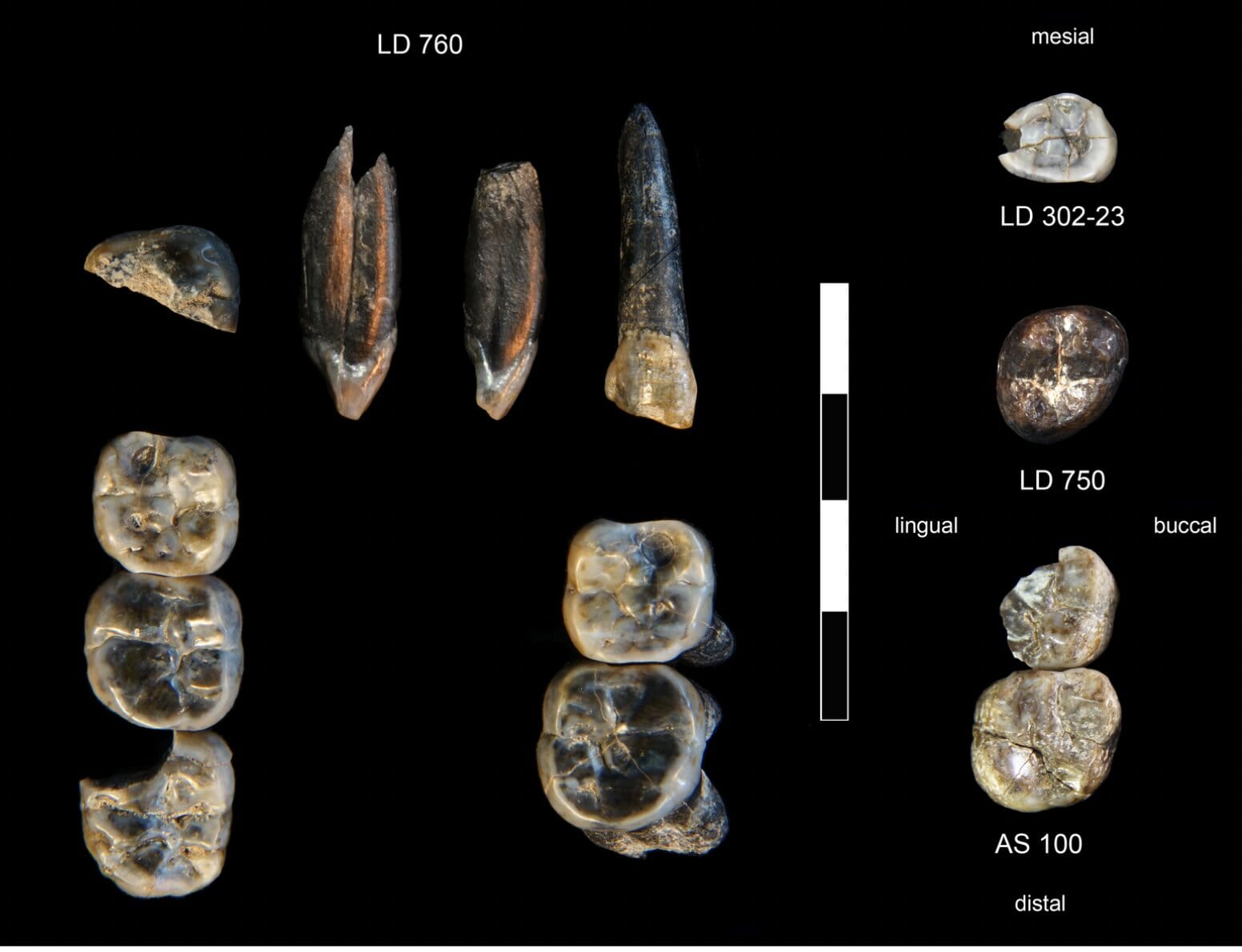

In the rugged badlands of Ethiopia’s Afar region, a team of international scientists has uncovered a fossil discovery that’s rewriting a key chapter in the story of human origins. At a site called Ledi-Geraru, researchers found 13 teeth—some belonging to the earliest known members of our own genus, Homo, and others to a completely new species of Australopithecus never before seen.

Even more surprising, the fossils show that these two ancient relatives lived in the very same place between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago.

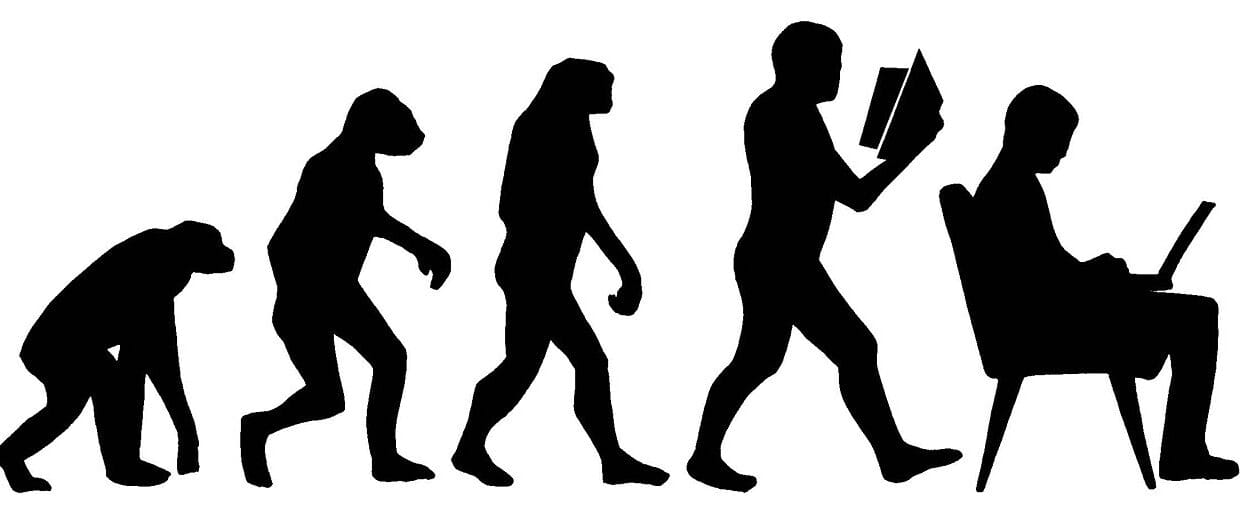

The discovery, detailed in the journal Nature, offers a vivid snapshot of a time when human evolution was not a neat, single-file march from apes to modern humans—but a tangled, branching network of different species sharing the same ground.

“This new research shows that the image many of us have in our minds of an ape to a Neanderthal to a modern human is not correct—evolution doesn’t work like that,” said Kaye Reed, paleoecologist at Arizona State University and co-director of the Ledi-Geraru Research Project. “It’s a bushy tree, with lifeforms that sometimes live together and sometimes disappear.”

A Site Already Famous for Firsts

Ledi-Geraru is no stranger to headlines. In 2013, Reed’s team unearthed the jawbone of the oldest known Homo specimen—dated to 2.8 million years ago—and the earliest Oldowan stone tools ever found on Earth. This time, the find is smaller but no less groundbreaking: teeth that tell a tale of coexistence between two different hominin species at the dawn of our lineage.

Lead author Brian Villmoare, an ASU alumnus, explained why these tiny fossils matter so much:

“We know what the teeth and mandible of the earliest Homo look like, but that’s it. Finding these additional teeth emphasizes how little we still know about the differences between Australopithecus and Homo, and how they could overlap in the same location.”

Dating Ancient Lives with Volcanoes

To determine the fossils’ age, the team turned to the land itself. The Afar region is part of an active geological rift—an area once dotted with volcanoes whose eruptions left behind layers of ash rich in crystals called feldspars. These crystals are nature’s time capsules.

“When volcanoes erupted, they scattered ash that we can date very precisely,” said Christopher Campisano, geologist at ASU. “Because the fossils are sandwiched between these layers, we can determine their age by dating the ash above and below them.”

The team’s careful work revealed that both Homo and the new Australopithecus species walked the same soil sometime between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago.

A Landscape of Change

The Ledi-Geraru of today is a harsh, eroded expanse of gullies and ridges baked under the Ethiopian sun. But in the late Pliocene, the scene was far different.

“Back then, rivers wandered across a green landscape, feeding into shallow lakes that expanded and shrank over time,” Reed explained. This environment would have offered plenty of resources—water, vegetation, and perhaps opportunities for scavenging or hunting—to both Homo and Australopithecus.

Were these ancient cousins competing for food, or did they find ways to coexist? Did they even cross paths? No one can say for sure, but the questions drive researchers deeper into the field and the fossil record.

The Mystery of the New Australopithecus

While the teeth clearly represent a species of Australopithecus never found before, the researchers cannot yet give it a formal name. More skeletal material is needed to understand its anatomy, behavior, and relationship to other species.

What they can say is that it’s not Australopithecus afarensis—the species of the famous “Lucy.” In fact, the new fossils confirm there is still no evidence of Lucy’s kind younger than 2.95 million years ago.

“This is an important clue,” said Reed. “It shows that Lucy’s species had disappeared from the fossil record by this time, making room for other Australopithecus species and early Homo to emerge and overlap.”

Rewriting the Family Tree

For generations, popular imagination pictured human evolution as a straight line—primitive apes giving rise to Neanderthals, who in turn evolved into modern humans. But discoveries like this show reality was far more complex.

“It’s not a ladder; it’s a bush,” Reed said. “Species branched out, lived alongside each other, and sometimes went extinct, leaving us as the only survivors of a much larger family.”

That branching, overlapping family history makes each new fossil find especially precious. Even a tooth, no bigger than a fingernail, can shift the way scientists see our deep past.

What’s Next for Ledi-Geraru

The team is already studying the teeth in more detail, analyzing their enamel to learn about the species’ diets. Did early Homo and this new Australopithecus eat the same plants or animals? Were their food choices shaped by competition, cooperation, or chance? The answers may lie in the microscopic patterns of wear and chemical traces locked inside the enamel.

“Whenever you have an exciting discovery, you always know you need more information,” said Reed. “You need more fossils. That’s why we keep coming back—because the land still has stories to tell.”

A Shared Ancestral Story

Two and a half million years ago, in a lush, shifting landscape at the heart of Africa, two distant cousins stood on the same ground. One would give rise to the lineage that eventually became us. The other would vanish, leaving no living descendants.

We carry the legacy of those survivors, but discoveries like this remind us that we are just one branch of a much larger evolutionary tree—a tree still revealing its hidden roots.

More information: New discoveries of Australopithecus and Homo from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09390-4. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09390-4

Reed and Campisano talk more about this project in an in-depth interview.