Consciousness is one of the greatest mysteries of science. Why does it exist? What evolutionary advantage does it provide? These questions have baffled researchers for centuries. We are aware of our thoughts, sensations, and emotions, yet what purpose does this awareness serve? Why did it evolve in some species like humans, but not in others, such as oak trees or certain fish?

For decades, scientists have been trying to answer these questions, but the true function of consciousness remains elusive. Now, a groundbreaking study from Ruhr University Bochum in Germany offers a new perspective. The study, led by Professors Albert Newen and Onur Güntürkün, suggests that consciousness, far from being a rare, specialized trait, may actually be a more widespread and ancient phenomenon in the animal kingdom than we previously thought. And intriguingly, birds may hold the key to understanding the evolutionary advantages of consciousness.

Arousal, Attention, and the First Steps of Consciousness

To understand how consciousness evolved, it’s crucial to break it down into different types. The researchers at Ruhr University Bochum have categorized consciousness into three distinct stages: basic arousal, general alertness, and reflexive (self-)consciousness. Each stage represents a different evolutionary step, starting with the most fundamental.

Albert Newen explains that basic arousal is the earliest form of consciousness. This basic form of awareness emerged as a survival mechanism, helping organisms stay alive in dangerous situations. “Pain is an extremely efficient means for perceiving damage to the body and to indicate the associated threat to its continued life,” Newen says. Pain triggers survival responses, such as fleeing or freezing, ensuring the organism reacts quickly to harm.

The second stage is general alertness. This allows creatures to focus on specific stimuli, even when there is a flow of competing information. Imagine you are speaking with a friend when you suddenly notice smoke in the distance—your attention shifts entirely to the smoke, and you start searching for its source. This heightened focus is crucial for survival, helping organisms learn important correlations, such as the fact that smoke typically signals fire. It’s this focused attention that enables humans and animals to understand complex patterns in the world around them.

The third and final stage of consciousness is reflexive, or self-consciousness. This is the most complex form of awareness, where an organism reflects on its own existence, past experiences, and future plans. Newen describes reflexive consciousness as “conscious experience focusing not on perceiving the environment, but rather on the conscious registration of aspects of oneself.” This ability to self-reflect—like recognizing oneself in a mirror—emerges in humans around 18 months old and is also seen in certain animals, including chimpanzees, dolphins, and even magpies.

Birds: Unlikely Pioneers of Consciousness?

What is particularly exciting about this study is how it challenges previous assumptions about the evolution of consciousness. While many researchers have focused on mammals as the key to understanding consciousness, the Ruhr University Bochum team looked to birds to explore these questions in a new light.

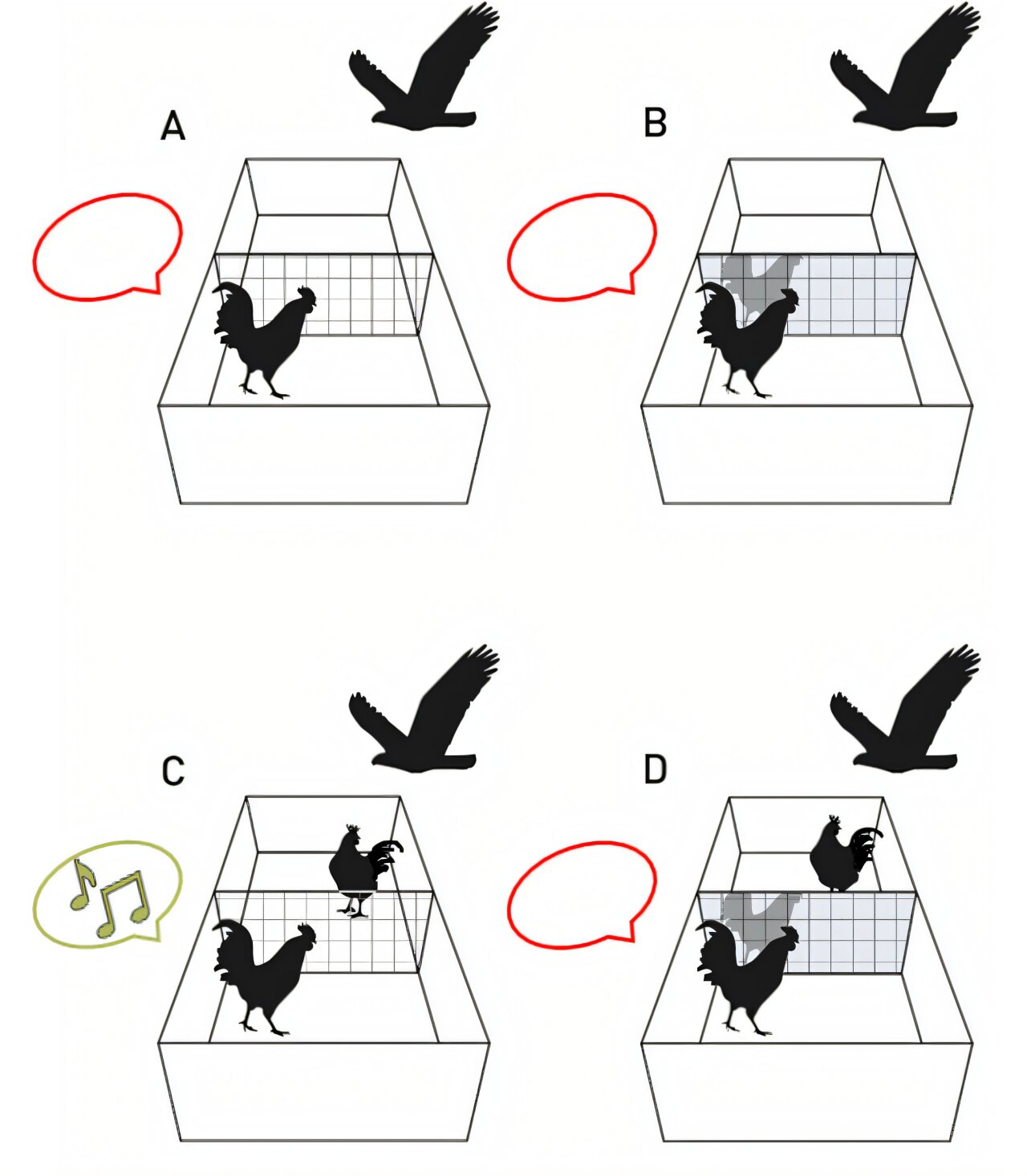

Birds, despite having different brain structures from mammals, may experience forms of consciousness remarkably similar to those of humans. Researchers Gianmarco Maldarelli and Onur Güntürkün highlight three central areas where birds show surprising parallels to conscious experience. The first is sensory consciousness—the ability to not just process sensory information but to subjectively experience it. Studies have shown that pigeons, for example, interpret ambiguous visual stimuli in ways that suggest they are consciously perceiving the world, not just reacting to it. “When pigeons are presented with ambiguous visual stimuli, they shift between various interpretations, similar to humans,” Maldarelli explains.

This ability to process sensory information subjectively is also seen in crows. Recent research revealed that crows exhibit nerve signals that do not directly correlate to the physical stimulus but reflect the crow’s internal experience. Sometimes a crow will perceive a stimulus consciously, and at other times, it will not—suggesting a deeper level of awareness about its surroundings.

A New Understanding of Brain Structure and Consciousness

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the study is the discovery that birds, despite lacking a cerebral cortex, have brain structures that support conscious processing. In mammals, the cerebral cortex is thought to be essential for higher-level cognitive functions, including conscious thought. But birds appear to accomplish similar feats with a different arrangement.

The avian brain contains a structure called the NCL, which acts as the brain’s equivalent of the prefrontal cortex in mammals. The NCL is highly interconnected, allowing for the flexible processing of information. “The connectome of the avian forebrain, which presents the entirety of the flows of information between the regions of the brain, shares many similarities with mammals,” says Güntürkün. This suggests that, while birds’ brains are organized differently from mammals’, they still meet many of the criteria needed for conscious processing, as outlined in theories like the Global Neuronal Workspace theory.

Self-Consciousness in Birds: More Than Meets the Eye

The study goes even further, revealing evidence that birds may possess self-consciousness—a trait that was once thought to be unique to humans and a few other mammals. In a series of experiments, pigeons and chickens were shown their own reflections in mirrors and responded by differentiating their own image from that of another bird. This kind of situational self-awareness suggests that these birds possess a basic form of self-consciousness, which is a critical step toward more complex forms of awareness.

For example, crows, known for their intelligence, have passed the traditional mirror test, a classic measure of self-recognition. But the research team also explored other, more ecologically relevant tests of self-perception, revealing that different species of birds demonstrate varying levels of self-consciousness depending on the context. This is an important finding, as it suggests that self-awareness may not be a monolithic trait, but one that varies across species.

The Implications: Consciousness May Be Older and More Widespread Than We Thought

What do these findings mean? First and foremost, they challenge the assumption that consciousness is a trait confined to mammals, especially humans. Birds, despite their fundamentally different brain structure, may experience consciousness in ways strikingly similar to mammals. This suggests that consciousness may be an older, more widespread phenomenon in the animal kingdom than previously assumed.

In fact, these findings offer a compelling argument that consciousness may not be the result of a single evolutionary leap but rather an adaptive feature that evolved independently in different lineages. The research shows that, while the pathways to consciousness may vary, the benefits of having a conscious experience—such as better survival through pain detection, heightened awareness, and self-reflection—are universal.

This study opens up exciting possibilities for further research into the evolution of consciousness. Understanding how different species, including birds, develop self-awareness and perceive their environment could have profound implications not only for biology but for fields like artificial intelligence, ethics, and animal cognition. It forces us to rethink what it means to be “conscious” and raises the tantalizing possibility that, even in creatures with vastly different brains, the basic experience of being aware may unite us all.

Ultimately, this research reveals that consciousness, far from being a rare, unique trait, may be an ancient and widespread evolutionary advantage. It underscores the idea that consciousness has evolved in many forms across the animal kingdom to help species better adapt to their environments, survive, and thrive. In a world where awareness is often taken for granted, these findings remind us just how extraordinary—and essential—consciousness truly is.

More information: Albert Newen et al, Three types of phenomenal consciousness and their functional roles: unfolding the ALARM theory of consciousness, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2024.0314

Gianmarco Maldarelli et al, Conscious birds, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2024.0308