In the vast world of mammals, cancer is an all-too-common threat. It’s a disease that has plagued species from the smallest rodents to the largest whales. Yet, amidst this grim reality, a handful of extraordinary animals seem to have cracked the code to resisting cancer. Among them are the naked mole rat, the unassuming elephant, and a few others, whose remarkable ability to avoid the disease has long puzzled scientists. Why do these creatures defy the odds while most of their mammalian relatives succumb to the ravages of uncontrolled cell growth?

New research has uncovered a fascinating possibility: the secret to their cancer resistance may not be hidden deep within their genetics but in the way they live. According to a groundbreaking study published in Science Advances, these animals may owe their resilience to their deeply interdependent social structures, where cooperation, care, and mutual support are at the heart of their existence.

The Puzzle of Cancer and the Social Animal

At first glance, cancer may seem like a random affliction—a byproduct of the slow decay that comes with aging and the accumulation of mutations over time. After all, the disease arises from uncontrollable cell growth, turning once-healthy cells into malignant tumors. It’s a deadly mistake of biology. Or so we thought.

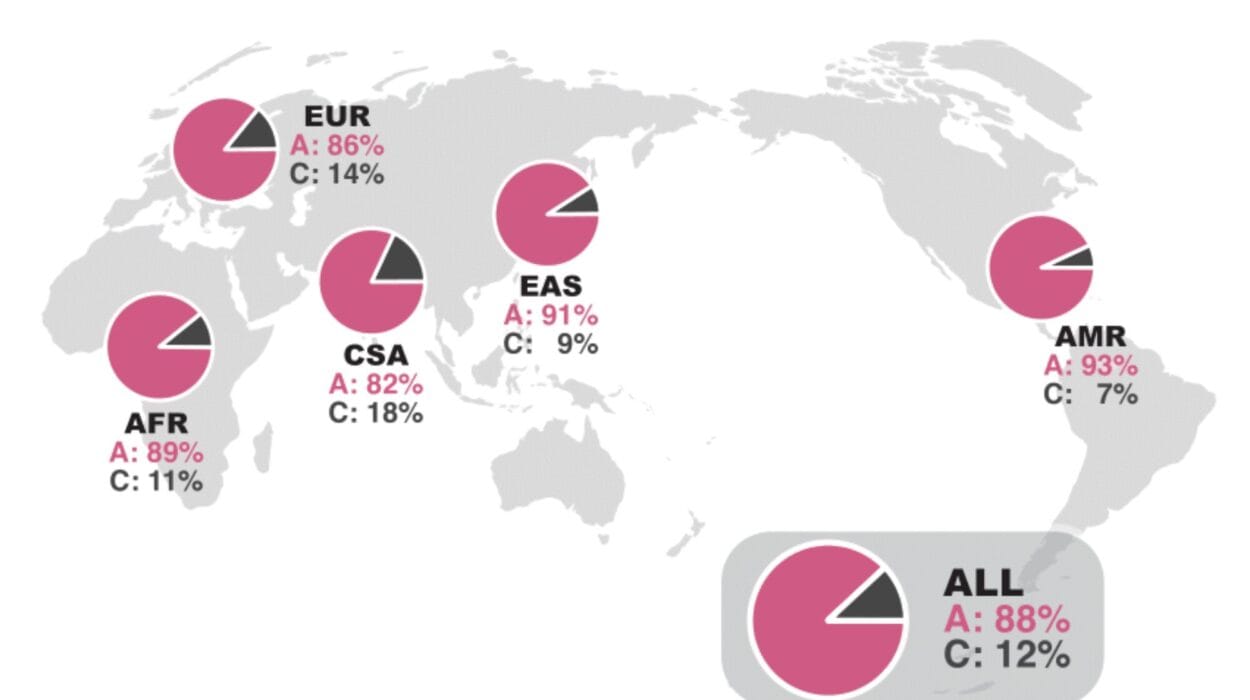

This study challenges that conventional wisdom. By analyzing a wide range of mammals, researchers noticed an intriguing pattern: cancer rates were higher in species that lived solitary lives, fiercely competed for resources, and raised large litters of offspring. In contrast, species that thrived in social groups, where cooperation and care were central to survival, had significantly lower cancer rates.

“Species with higher intraspecific competition display higher cancer prevalence and mortality risk than gregarious species with cooperative and caring habits, even if they are carnivorous,” the researchers noted in their paper.

It was a revelation that shifted the focus of cancer research from just genetics to the environment and social dynamics of species. The animals that lived in tight-knit communities, where survival depended on looking out for one another, seemed to be the ones who had the upper hand in the battle against cancer.

The Hydra Effect: A Mythical Clue

To understand this unexpected connection between social behavior and cancer resistance, the research team introduced an intriguing concept known as the Hydra Effect. Named after the mythical hydra—whose severed heads grew back in twos—the Hydra Effect describes a counterintuitive phenomenon in nature. When older members of a species die, their removal can actually benefit the population, leading to an increase in numbers rather than a decline.

But how does this relate to cancer?

The researchers built a mathematical model to explore how the death of older, non-reproductive individuals might affect the population dynamics of different species, particularly those that were either competitive or cooperative. In competitive species, the model showed that older individuals consumed resources and occupied territory without contributing to reproduction. When these older individuals were removed—whether by aging, disease, or cancer—their absence freed up resources for the younger, reproductive members of the population. In essence, cancer seemed to “clear the way” for younger, more fertile animals to thrive.

“The death of older individuals removes competition, opening up resources for the younger generation,” the researchers explained. Cancer, in this case, appeared to play a role in facilitating the survival of the species by promoting the success of younger, more reproductive individuals.

Cooperation Blocks the Hydra Effect

However, the researchers quickly discovered that the Hydra Effect doesn’t apply to every species. In cooperative species—those that live in social groups, where individuals care for one another—the dynamics shift. In these species, the death of older individuals due to cancer would disrupt the entire social structure and jeopardize the survival of the group. Older animals in social species are often key figures in the survival of the group, acting as protectors, caregivers, or leaders. The loss of these individuals would risk the safety and wellbeing of the younger members, undermining the benefits of the cooperative system.

This is where cancer’s role changes dramatically. In social species, cancer doesn’t “clear the way” for the younger generation; instead, it threatens the delicate balance that allows the group to function. Older individuals, rather than being a drain on resources, are crucial for the survival of the young. This is why species like elephants, naked mole rats, and others with tight social structures have evolved resistance to cancer—because cancer would be a death sentence for the entire community.

What This Means for Human Health

If cancer is not just a random genetic fluke but a trait shaped by evolutionary pressures related to social behavior, this research could have profound implications for how we approach aging and cancer prevention. Could the cooperative habits of certain animals offer us clues about how to reduce cancer risk in humans?

By studying the social lives of animals that have evolved resistance to cancer, researchers may be able to uncover new strategies for healthier aging. These animals—whether they are the nurturing elephants or the cooperative mole rats—demonstrate that living in close-knit, supportive communities might be one key to avoiding cancer. It’s not just about genetic mutations or the wear and tear of life; the way we live, the way we care for each other, could be a crucial factor in determining our risk.

The findings from this study suggest that, like these social animals, humans might benefit from fostering more cooperative, interdependent social structures. A society that values care, support, and mutual responsibility may not only improve quality of life but also protect against some of the most challenging diseases, including cancer.

Why This Research Matters

This research is a game-changer because it shifts the focus of cancer research from a purely genetic perspective to one that incorporates behavior, social structures, and evolutionary biology. It forces us to rethink the way we view cancer, no longer as just a random disease but as something deeply intertwined with the life history and social habits of a species.

It also opens up new possibilities for cancer prevention. The study suggests that understanding the complex ways in which animals like elephants and mole rats have evolved to resist cancer could inspire new strategies for human health. If social behavior can influence cancer resistance, could building stronger, more cooperative communities help us live healthier, longer lives?

This research is a reminder that nature’s solutions are often far more complex and interconnected than we might imagine. In the quiet, social lives of these cancer-resistant mammals, there may lie the key to unlocking a healthier future for all.

More information: Catalina Sierra et al, Coevolution of cooperative lifestyles and reduced cancer prevalence in mammals, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adw0685