For more than twenty years, a seven-million-year-old fossil from the sands of Chad has hovered in a scientific gray zone. It was old enough to sit near the very root of the human family tree, yet ambiguous enough to resist clear classification. Its name, Sahelanthropus tchadensis, became shorthand for a question that refused to go away: did this ancient creature walk upright, or did it still move through the world on all fours like the apes we know today?

The answer mattered enormously. If Sahelanthropus was bipedal, then it would stand as the oldest known human ancestor, reshaping our understanding of when and how upright walking evolved. If not, it might belong to a side branch of ape evolution, fascinating but ultimately separate from our own story. For decades, scientists argued, reexamined, and disagreed.

Now, a new analysis has tipped the balance. By peering deep into the fossilized bones with modern tools and careful comparison, a team of anthropologists has uncovered a feature that speaks clearly and unmistakably of life on two legs. The fossil, it turns out, had been holding onto its secret all along.

The Bone That Changed the Argument

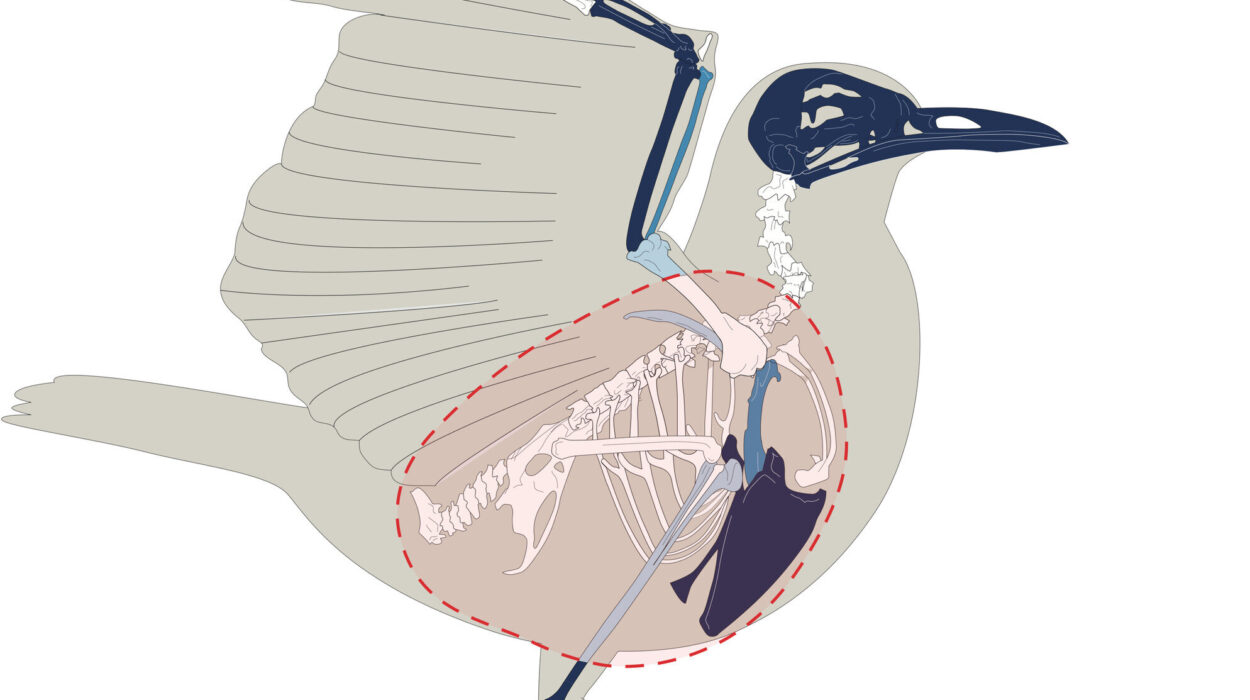

At the center of the new research is a subtle but powerful anatomical marker: the femoral tubercle. This small structure, found on the thigh bone, is the attachment point for the iliofemoral ligament, described as the largest and most powerful ligament in the human body. Its role is essential. It stabilizes the hip during upright posture and makes efficient walking possible.

What makes the femoral tubercle so compelling is not just what it does, but where it has been found before. According to the researchers, this feature has so far been identified only in bipedal hominins. Its presence is not a vague hint or an interpretive guess. It is a direct anatomical signature of walking upright.

Using 3D technology and other analytical methods, the research team identified this tubercle on the Sahelanthropus femur. In doing so, they uncovered something no previous study had demonstrated so clearly: a structural commitment to bipedal movement embedded in bone.

This was not a reinterpretation of old assumptions. It was a new line of evidence, grounded in anatomy, emerging from a fossil that had already sparked controversy for decades.

A Creature Caught Between Two Worlds

The discovery does not paint Sahelanthropus as a simple, fully humanlike walker striding confidently across open plains. Instead, it reveals a more complex and intriguing picture, one that blends the familiar and the unexpected.

“Sahelanthropus tchadensis was essentially a bipedal ape that possessed a chimpanzee-sized brain and likely spent a significant portion of its time in trees, foraging and seeking safety,” says Scott Williams, an associate professor in New York University’s Department of Anthropology who led the research.

This description places Sahelanthropus in a world of transition. It was adapted for upright posture and movement on the ground, yet still deeply connected to life in the trees. Its brain size aligned with that of modern chimpanzees, not later human ancestors. Its body suggests an organism navigating two environments, shifting between branches and ground as circumstances demanded.

“Despite its superficial appearance, Sahelanthropus was adapted to using bipedal posture and movement on the ground.”

That contrast is striking. Outwardly, Sahelanthropus may have looked far more like an ape than a human. Inwardly, its bones tell a different story, one of evolutionary experimentation at the dawn of the human lineage.

A Discovery Rediscovered

Sahelanthropus was first uncovered in the early 2000s in Chad’s Djurab desert by paleontologists from the University of Poitiers. The initial excitement focused almost entirely on the skull, which showed a mix of primitive and potentially humanlike features. From the start, interpretations diverged.

Years later, attention turned to other fossilized remains found at the same site. These included parts of the forearm, known as the ulnae, and the femur. When studies of these bones were reported two decades after the original discovery, they reopened the debate rather than settling it. Some scientists saw signs of bipedalism. Others remained unconvinced.

The question lingered: was Sahelanthropus truly a hominin, a member of the human lineage, or merely a close relative that never walked the same path?

The new study, published in Science Advances, approached the problem with renewed focus and refined tools. Rather than relying on a single trait or broad impressions, the researchers conducted a detailed, multi-layered analysis of the ulnae and femur.

Reading the Shape of Evolution

The team employed two primary methods to extract meaning from ancient bone. One involved comparing multiple traits across the same bones in living species and fossil relatives. The other used 3D geometric morphometrics, a standard technique that allows scientists to analyze shapes in fine detail and identify patterns that might otherwise remain hidden.

These methods allowed the researchers to move beyond surface similarities and examine how the bones were structured, twisted, and proportioned. Among the fossil species included in their comparisons was Australopithecus, an early human ancestor known famously through the discovery of the “Lucy” skeleton in the early 1970s. Australopithecus lived between four and two million years ago and is widely accepted as bipedal.

Against this backdrop, the Sahelanthropus fossils began to speak more clearly.

The analysis revealed not only the femoral tubercle, but also a natural twist in the femur known as femoral antetorsion. This twist helps orient the legs forward and plays a crucial role in efficient walking. In Sahelanthropus, the degree of this twist fell squarely within the range seen in hominins.

The 3D analysis also illuminated the structure of the gluteal muscles. These buttock muscles are essential for stabilizing the hips during standing and walking. In Sahelanthropus, their arrangement closely resembled that of early hominins, supporting upright posture and movement.

Importantly, the latter two traits had been identified by other scientists in earlier work. The new study did not overturn those findings but affirmed them, strengthening the case by bringing all lines of evidence together.

Proportions That Tell a Story

Beyond individual features, the researchers examined overall limb proportions. They found that Sahelanthropus had a relatively long femur compared to its ulna. This ratio matters because it reflects how an animal moves through its environment.

Apes tend to have long arms and short legs, an adaptation for climbing and swinging through trees. Hominins, by contrast, have relatively long legs, which support upright walking. Sahelanthropus did not have legs as long as modern humans, but its proportions were distinct from those of apes.

In fact, its relative femur length approached that of Australopithecus. This suggests another step toward bipedal adaptation, reinforcing the idea that upright walking was already taking shape at this early stage.

Together, these anatomical clues converge on a single conclusion. Sahelanthropus was not merely experimenting with upright posture. It was capable of walking on two legs.

Rewriting the Opening Chapter of Human History

“Our analysis of these fossils offers direct evidence that Sahelanthropus tchadensis could walk on two legs, demonstrating that bipedalism evolved early in our lineage and from an ancestor that looked most similar to today’s chimpanzees and bonobos,” concludes Williams.

This statement carries profound implications. It suggests that the shift toward upright walking did not arise from a creature that already looked markedly human. Instead, it emerged from an ancestor that, in many ways, still resembled modern apes.

Bipedalism, long considered a defining trait of humanity, appears to have evolved earlier than previously confirmed and within a body plan that retained many ape-like characteristics. This challenges simple narratives of linear progress and highlights evolution as a process of overlapping adaptations rather than sudden transformations.

The study itself reflects a collaborative effort across institutions, including researchers from New York University, the University of Washington, Chaffey College, and the University of Chicago. Their work does not merely settle an old argument. It reshapes the context in which that argument was framed.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it anchors one of humanity’s most defining traits deep in time and complexity. Walking upright is not just a mechanical change; it reshaped how our ancestors interacted with their environment, freed their hands, altered their social behaviors, and set the stage for everything that followed.

By showing that bipedalism existed in a creature with a chimpanzee-sized brain and strong ties to arboreal life, the study underscores that human evolution did not begin with intelligence or tool use. It began with movement. It began with posture. It began with bones quietly adapting to a new way of being in the world.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis no longer stands as a question mark at the edge of our family tree. Through careful analysis and patient inquiry, it has stepped forward as an early walker, balanced between branches and ground, carrying within its femur a clue to the path our ancestors would one day follow.

More information: Scott Williams, Earliest evidence of hominin bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv0130. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adv0130