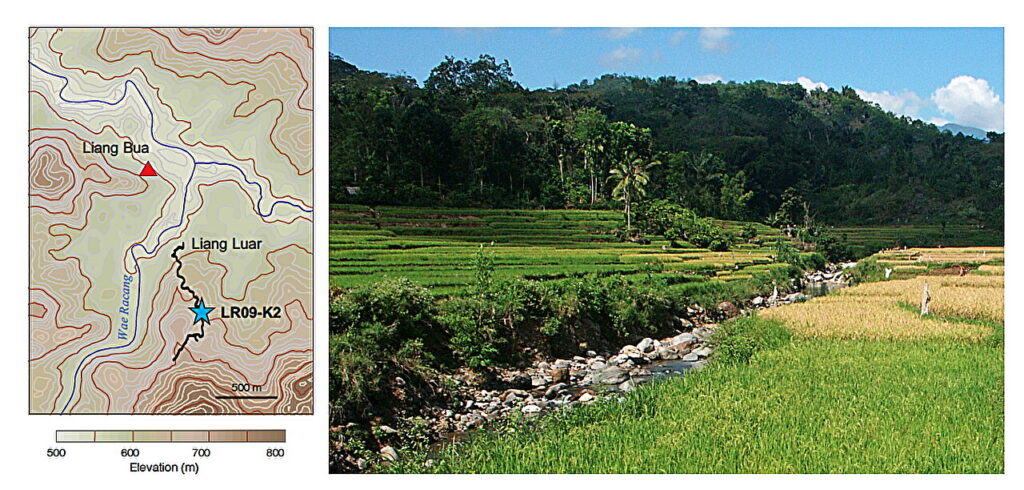

For nearly 140,000 years, a cave on the Indonesian island of Flores sheltered a small-bodied human species whose very existence would one day challenge everything we thought we knew about human evolution. Liang Bua was not just a shelter. It was a home, a hunting ground, a place where generations lived and died beneath the same stone ceiling. Then, quietly and permanently, the cave was abandoned.

What happened to the so-called hobbits, known scientifically as Homo floresiensis, has long been one of the most haunting questions in paleoanthropology. Their fossils vanish from the record around 50,000 years ago, leaving behind stone tools, bones, and a profound silence. Now, new research suggests the answer may have been written not in sudden catastrophe, but in slow, relentless drying skies.

An international team of scientists, including researchers from the University of Wollongong, has uncovered compelling evidence that a changing climate played a critical role in the disappearance of these early humans. By reading chemical signals preserved in stone and teeth, the researchers have reconstructed a story of dwindling rainfall, stressed ecosystems, and a fragile balance that finally broke.

When the Rains Began to Fail

The story begins not with the hobbits themselves, but with water. Or more precisely, with its absence.

Deep inside Liang Bua and nearby caves, stalagmites have been quietly growing for tens of thousands of years, layer by layer, drip by drip. These mineral formations are more than geological curiosities. They are natural archives, preserving chemical signatures that reflect the rainfall patterns of the past. By analyzing these layers, scientists can peer back in time and reconstruct ancient climates with remarkable detail.

The research team combined these stalagmite records with isotopic data from fossil teeth belonging to Stegodon florensis insularis, a pygmy elephant species that once roamed Flores and served as a crucial food source for Homo floresiensis. Together, the stone and the teeth told the same story.

Around 76,000 years ago, the region began to dry. Rainfall gradually declined, setting off an environmental shift that would intensify over thousands of years. Between 61,000 and 55,000 years ago, the area experienced a severe and prolonged drought. Rivers that once flowed reliably became seasonal. Surface freshwater grew scarce. The landscape that had sustained life for millennia was changing.

“The ecosystem around Liang Bua became dramatically drier around the time Homo floresiensis vanished,” said UOW Honorary Professor Dr. Mike Gagan, the lead author of the study. “Summer rainfall fell and riverbeds became seasonally dry, placing stress on both hobbits and their prey.”

Reading History in Stone and Bone

To understand how this drying climate affected life on Flores, the researchers turned to an unlikely pair of witnesses: cave stalagmites and fossilized elephant teeth.

Stalagmites form from dripping water, and the oxygen isotopes locked within them reflect the amount and source of rainfall at the time each layer formed. By carefully analyzing these isotopes, the team reconstructed a long-term record of changing precipitation. What emerged was a clear trend toward aridity, culminating in the harsh drought that coincided with the hobbits’ disappearance.

The fossil teeth added another crucial layer to the story. The enamel of Stegodon teeth contains isotopic signatures that reveal what kind of water the animals drank. The analysis showed that these pygmy elephants depended heavily on river water. As rivers dried up, the elephants faced increasing stress.

The data revealed a sharp decline in the Stegodon population around 61,000 years ago. This was not an isolated event. It aligned closely with the period of severe drought identified in the stalagmite records and with the timeframe in which Homo floresiensis began to disappear from Liang Bua.

“Surface freshwater, Stegodon and Homo floresiensis all decline at the same time, showing the compounding effects of ecological stress,” UOW Honorary Fellow Dr. Gert van den Berg said. “Competition for dwindling water and food probably forced the hobbits to abandon Liang Bua.”

A Slow Unraveling of an Ecosystem

For Homo floresiensis, life on Flores had always required adaptation. Their small stature, once thought puzzling, may have been well suited to an island environment with limited resources. For tens of thousands of years, they survived by hunting pygmy elephants and other animals, relying on stable water sources and predictable seasonal cycles.

But prolonged drought does not negotiate. As rainfall decreased, rivers became unreliable. Vegetation would have changed. Prey animals, already stressed by limited water, declined in number. What had once been a balanced ecosystem began to unravel.

The research suggests that this was not a sudden collapse but a slow squeeze. Each dry season would have lasted a little longer. Each riverbed would have stayed empty a little more often. For a species finely tuned to its environment, these incremental changes could have been devastating.

Eventually, the pressures may have grown too great. Faced with dwindling food and water, Homo floresiensis appears to have abandoned Liang Bua, the cave that had been central to their existence for roughly 140,000 years. Where they went, and how long they survived afterward, remains unknown. What is clear is that they never returned.

The Shadow of Another Human Species

The disappearance of Homo floresiensis has always raised another tantalizing question: did they encounter modern humans?

The new findings add nuance to this mystery. Fossils of Homo floresiensis pre-date the earliest evidence of modern humans on Flores. However, Homo sapiens were moving through the Indonesian archipelago around the time the hobbits vanished from the fossil record.

As climate stress pushed the hobbits to search for new water sources and prey, their movements may have brought them into contact with modern humans for the first time.

“It’s possible that as the hobbits moved in search of water and prey, they encountered modern humans,” Dr. Gagan said. “In that sense, climate change may have set the stage for their final disappearance.”

The research does not claim that modern humans caused the extinction of Homo floresiensis. Instead, it suggests a more complex and subtle chain of events. Climate change may have weakened an already vulnerable population, reducing their numbers, fragmenting their habitats, and making survival increasingly difficult in a world that was no longer predictable.

A Mystery That Took Decades to Unravel

The discovery builds on decades of research by the University of Wollongong and its collaborators. Homo floresiensis was first discovered in Liang Bua in 2003, a finding that sent shockwaves through the scientific community. A tiny human species living until relatively recent times did not fit neatly into existing models of human evolution.

Since then, researchers have debated how these hobbits lived, where they came from, and why they disappeared. The new study does not close every chapter of that debate, but it brings a critical piece of evidence into focus.

By linking climate records with ecological data and fossil evidence, the researchers have shown how deeply environmental conditions can shape the fate of a species. The hobbits did not vanish in isolation. Their disappearance was intertwined with the drying of rivers, the decline of prey, and the shifting rhythms of rainfall.

Why This Story Still Matters

The extinction of Homo floresiensis is not just an ancient tragedy. It is a mirror held up to the present.

This research highlights how sensitive species can be to long-term environmental change, especially when resources like water become scarce. It shows that extinction does not always arrive with fire or impact or invasion. Sometimes it comes quietly, through seasons that no longer bring rain, through rivers that stop flowing, through food sources that slowly disappear.

By uncovering the role of climate in the fate of one of our closest relatives, the study deepens our understanding of how ecosystems, climate, and survival are inseparably linked. It reminds us that humans, too, are part of these systems, dependent on stable environments in ways we often underestimate.

The story of Homo floresiensis is a story written in stone and bone, preserved across tens of thousands of years, and finally read by modern science. It tells us that climate can reshape destinies, that survival is never guaranteed, and that the past still has urgent lessons to teach.

In the quiet chambers of Liang Bua, the stalagmites kept their records. The teeth of pygmy elephants held their memories. Together, they reveal how a changing climate helped bring an extraordinary human lineage to an end, and why understanding that history matters now more than ever.

More information: Michael K. Gagan et al, Onset of summer aridification and the decline of Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua 61,000 years ago, Communications Earth & Environment (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02961-3