For decades, the Antarctic icefish held a singular place in biology textbooks and scientific imagination. It was the fish that broke a rule most vertebrates seemed unable to escape. It lived without red blood cells. Its blood flowed not crimson, but pale and translucent, carrying no hemoglobin, the molecule almost universally responsible for transporting oxygen in animals. For H. William Detrich, professor emeritus of marine and environmental sciences, this strange creature once felt like a mystery neatly tied up.

“I thought the story was solved when we did our work on Antarctic icefishes,” Detrich said.

Then another fish appeared, slender as a thread, drifting through warm rivers and coastal waters half a world away. The Asian noodlefish did not belong to the frozen Southern Ocean. It lived in environments where oxygen was not especially abundant. Yet its blood, too, was white. And with that quiet fact, the story of blood, oxygen, and evolution opened again.

“But then the noodlefishes came along and surprised me,” Detrich said. “It turns out there may be more species than we think that don’t rely on red blood cells to transport oxygen.”

When the Old Explanation No Longer Fits

The Antarctic icefish made sense, at least in evolutionary terms. Detrich and his colleagues at Northeastern University had spent years examining their genomes, tracing how these fish came to lose their red blood cells. Over millions of years, icefish had deleted their hemoglobin genes entirely. The genetic machinery for making red blood cells simply vanished.

The environment explained why this radical loss did not mean extinction. Antarctic waters are frigid, and cold water can hold large amounts of dissolved oxygen. Icefish, Detrich explained, could survive by letting oxygen dissolve directly into their blood plasma rather than packing it into hemoglobin.

“That means that the Antarctic icefishes are able to rely on oxygen that’s physically dissolved in their blood fluid,” he said.

In that context, losing red blood cells was not a liability. It was an adaptation, sculpted slowly by the unique conditions of the Southern Ocean. The explanation was elegant. It fit the facts. It felt complete.

But the Asian noodlefish refused to cooperate with that narrative.

A White-Blooded Fish in Warm Water

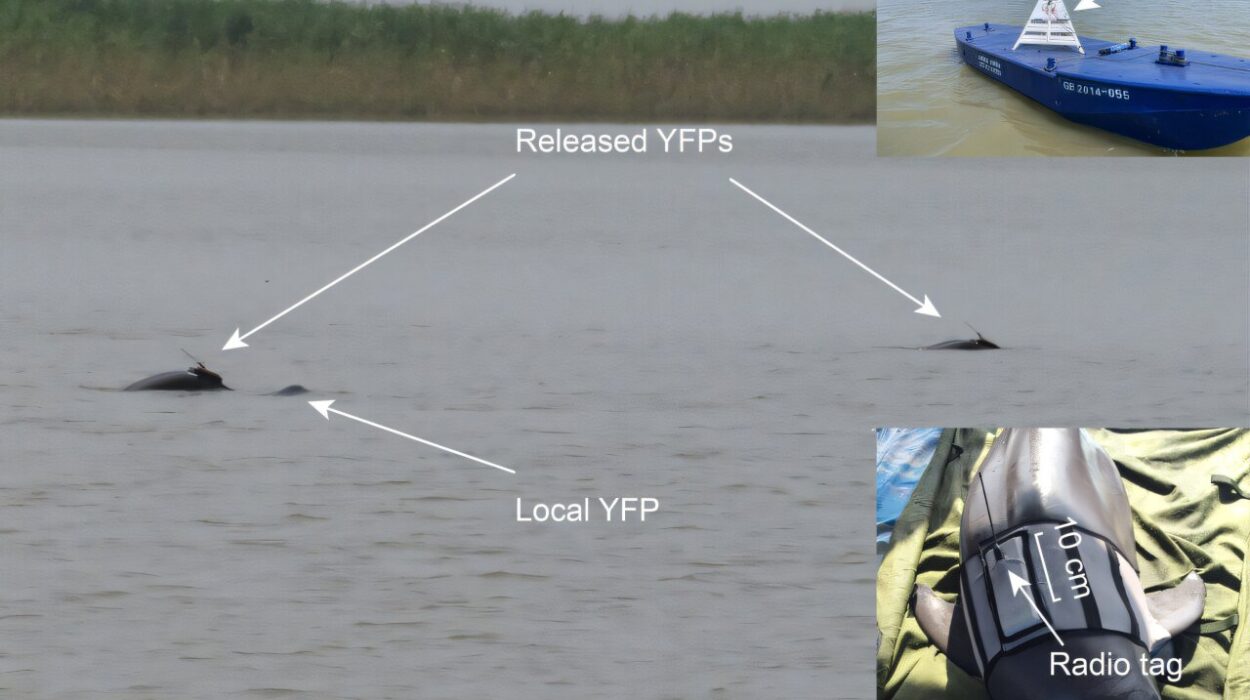

Asian noodlefish live far from Antarctica, swimming through the coasts and river systems of China, Korea, Japan and eastern Russia, extending south to Vietnam. These are warm waters, environments that do not offer the oxygen-rich advantage of polar seas.

“They live in a very different environment,” Detrich said. “They don’t have the advantage of a cold and oxygen-rich environment like the Southern Ocean.”

Yet their blood is also translucent white, lacking red blood cells and hemoglobin. The familiar explanation for icefish survival simply did not apply. If warm water holds less dissolved oxygen, how could these fish afford to abandon the primary oxygen-carrying system used by almost all vertebrates?

The puzzle crossed borders. Chinese scientists studying Asian noodlefish noticed the parallels with Antarctic icefish and reached out to Detrich. “They wanted to know what was going on,” he said. The question was no longer about one species in one extreme environment. It was about how evolution could arrive at the same astonishing outcome through entirely different routes.

Following the Genes Into Deep Time

One of the scientists who contacted Detrich was Jinxian Liu from the Qingdao Marine Science and Technology Center in Qingdao, China. Reading Detrich’s earlier work on icefish sparked an unsettling curiosity.

He wondered, as he later said, “whether our Asian noodlefishes … share a similar evolutionary pathway.”

The collaboration that followed focused on genetics, the long molecular record of evolutionary decisions. The scientists examined the hemoglobin genes, which produce the protein responsible for oxygen transport in red blood cells. They also looked closely at the gene for myoglobin, a related protein that binds oxygen within muscle cells and gives red meat its color.

What they found rewrote expectations.

“As part of this collaborative effort, we demonstrated that Asian noodlefish—all 12 species—have lost the myoglobin gene as a single event that occurred in their most recent common ancestor,” Detrich said.

That loss was total. Unlike hemoglobin, which still existed in damaged form, the myoglobin gene was gone altogether. The muscle cells of these fish no longer relied on it to manage oxygen.

Hemoglobin, however, told a different story.

“But unlike the icefishes, they hadn’t completely deleted the hemoglobin genes,” Detrich said. “Rather, they had smaller mutations that prevented the genes from expressing a functional hemoglobin protein.”

The noodlefish still carried the genetic remnants of hemoglobin, but those genes had been broken in subtle ways. The instructions remained, but they no longer worked.

A Life Lived Fast and Forever Young

The question remained: how could these fish survive, let alone thrive, with such limited oxygen transport in warm water? The answer, Detrich suggested, might lie not only in their genes, but in their lives.

Asian noodlefish live fast. Their entire life span unfolds in about a year. Compared with Antarctic icefish, which can live six or seven years or more, noodlefish are brief sparks in evolutionary time.

Although adult noodlefish can reproduce at the end of their short lives, they retain many juvenile features. Their bodies remain small, slender, and delicate. This arrested development is known as neoteny, and it may hold the key to their survival.

“In a number of other fish species, juveniles don’t need to make red blood cells because they are small and slender and can absorb oxygen through their scaleless skins,” Detrich said.

For most fish, this is only a temporary state. As they grow larger and thicker, they begin producing red blood cells to meet increasing oxygen demands. Asian noodlefish never make that transition. They remain, in a biological sense, juveniles for their entire lives.

Because of their size and shape, oxygen can diffuse directly through their skin and tissues without the need for hemoglobin-packed red blood cells. What would be a fatal limitation in a larger, longer-lived fish becomes a workable strategy in a tiny, short-lived one.

Two Paths, One Astonishing Outcome

When viewed side by side, Antarctic icefish and Asian noodlefish tell a remarkable evolutionary story. Both lack red blood cells. Both swim with white blood. Yet the reasons they arrived at this state could not be more different.

Icefish lost hemoglobin through complete gene deletion and compensated with an environment saturated in oxygen. Noodlefish damaged their hemoglobin genes without fully deleting them, lost myoglobin entirely, and relied on small size, rapid life cycles, and juvenile traits to survive in warmer waters.

Comparing these two lineages reveals how evolution is not a straight road but a branching maze.

“It’s a different set of environmental circumstances and a different set of molecular outcomes,” Detrich said.

Liu framed the finding in broader evolutionary terms. “The work is important because it shows that historical contingency also plays an important role in the evolution of biodiversity,” he said.

In other words, where a species starts, what challenges it faces, and which genetic changes happen first can shape outcomes just as much as the environment itself. There is no single script for survival.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, the story of white-blooded fish may seem like an oddity, a biological curiosity confined to obscure species. But its significance runs deeper.

This research shows that even traits once thought essential, like red blood cells, can be lost under the right circumstances. It reveals that evolution does not follow one optimal path, but many workable ones. Different environments, life histories, and genetic accidents can converge on similar solutions through entirely different mechanisms.

By comparing Asian noodlefish and Antarctic icefish, scientists gain a clearer picture of how biodiversity arises, not just through adaptation to the environment, but through the complex interplay of history, chance, and constraint.

For Detrich, the discovery carried a personal satisfaction as well. He and his colleagues saw their work published in the July issue of Current Biology, with the Asian noodlefish featured on the cover.

“There’s more than one way for fish to lose the production of myoglobin, hemoglobin and red blood cells—that’s what we discovered in this paper,” Detrich said.

The universe of life, it turns out, is far more inventive than any single explanation. Sometimes, the blood that tells the clearest evolutionary story is the blood that has lost its color entirely.

More information: Yu-Long Li et al, Independent evolutionary deterioration of the oxygen-transport system in Asian noodlefishes and Antarctic icefishes, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.050