Major depressive disorder (MDD) is more than sadness. It’s a deep, life-altering condition that casts a long shadow over everyday experiences, relationships, and physical health. With millions across the globe affected—about 3.5% of the world’s population, according to estimates—understanding the biological underpinnings of depression has become one of the most urgent challenges in neuroscience and psychiatry.

Now, new research from a team at Aachen University and Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH may be bringing scientists closer to understanding one piece of that complex puzzle. Their study, recently published in Translational Psychiatry, identifies a brain region whose structural changes appear to be linked to both depression and a personality trait long associated with mood disorders—neuroticism.

The area in question, the parahippocampal cortex (PHC), plays a key role in memory, emotional regulation, and spatial cognition. And according to the findings, its thinning could be a critical marker in identifying individuals vulnerable to depression.

Where Memory Meets Emotion

The parahippocampal cortex doesn’t usually make headlines, but in the quiet folds of this tucked-away brain region, something important may be happening in people struggling with depression. Nestled in the medial temporal lobe (MTL), the PHC has long been known to support memory formation and spatial awareness. More recently, research has also revealed its role in emotional memory and processing—skills that are often disrupted in major depression.

According to the study’s lead authors—Dominik Nießen and Ravichandran Rajkumar—the PHC may not just be a passive bystander in depressive illness. Rather, it might be structurally altered in a way that reflects both the severity of depression and the personality traits that increase a person’s vulnerability to developing it.

Their hypothesis was guided by what’s known as the cognitive model of depression—a framework suggesting that distortions in thinking, memory, and emotional perception are not merely symptoms but possible root causes of the disorder. If the brain’s infrastructure responsible for processing emotional memories is compromised, might that contribute to the persistent sadness and hopelessness that defines MDD?

Neuroticism and Depression: A Shared Brain Signature?

One of the most compelling aspects of the study is its focus not just on clinical depression, but also on neuroticism—a psychological trait characterized by a tendency to experience negative emotions like anxiety, fear, sadness, and anger. While not a mental illness itself, neuroticism has long been recognized as a risk factor for developing MDD.

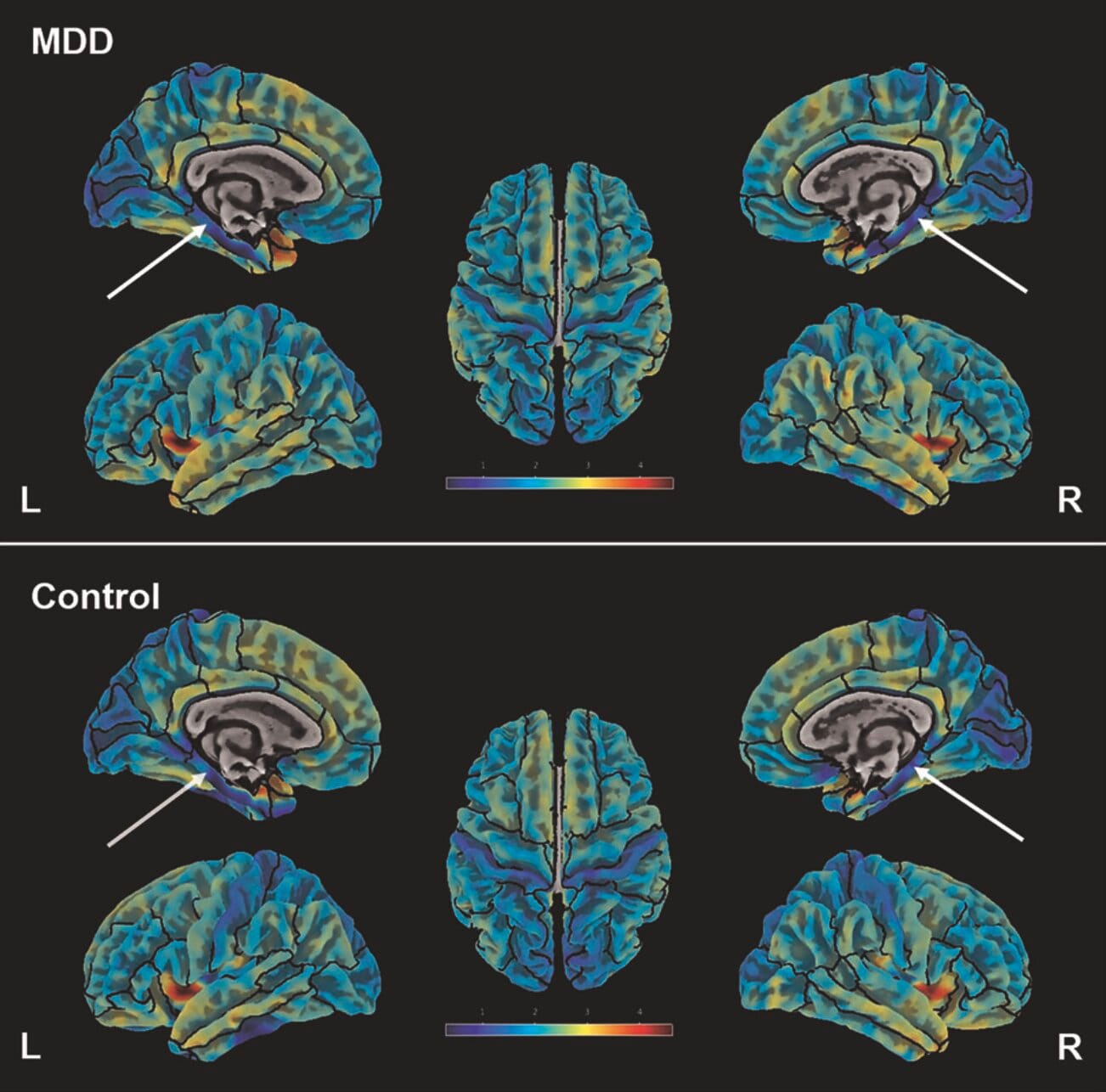

Previous studies hinted that people with high levels of neuroticism might show subtle changes in brain structure. But this new study takes a deeper dive, linking those structural changes to a very specific brain region using ultra-high field structural MRI at 7 Tesla—an advanced imaging technique that offers extraordinary resolution.

In doing so, the researchers uncovered a striking overlap: both individuals diagnosed with MDD and those who scored high on neuroticism tests had reduced cortical thickness in the parahippocampal cortex, especially in the left hemisphere.

Scanning the Depressed Brain

To explore these patterns, Nießen, Rajkumar, and their colleagues recruited 86 adult participants. Half had been diagnosed with MDD, while the other half served as healthy controls. The average age across the group was 31.4, with participants ranging from 18 to 61 years old. Roughly equal numbers of men and women took part, creating a well-matched sample.

Each participant underwent a high-resolution MRI scan and completed personality assessments using the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), a widely-used tool for measuring traits like openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and, most crucially here, neuroticism.

What emerged from this carefully controlled study was a clear, statistically significant finding: people with higher neuroticism scores had thinner parahippocampal cortices—on both sides of the brain. Among those diagnosed with MDD, the reduction in thickness was even more pronounced on the left side.

Why Cortical Thickness Matters

To understand the significance of these findings, it helps to appreciate what cortical thickness means in neuroscience. The cortex is the brain’s outer layer, where much of the complex processing of thought, memory, and emotion takes place. The thickness of the cortex is often used as a proxy for the integrity of that region—its health, connectivity, and level of activity.

Thinner cortex in specific areas has been linked to a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and now, it appears, major depression.

The PHC’s thinning may signal weakened neural networks in regions critical to encoding and retrieving emotionally charged memories—possibly making it harder for individuals to reframe negative experiences, resist ruminative thinking, or recall positive emotional moments.

In essence, a thinner PHC could structurally support the very symptoms that define depression: persistent sadness, difficulty in regulating emotions, and a tendency to dwell on the negative.

A New Biomarker on the Horizon?

The implications of this study are far-reaching. If replicated in larger and more diverse populations, PHC thickness could become a biomarker—a biological signal that helps in diagnosing or predicting disease.

Currently, depression is diagnosed based on subjective reporting: how a person feels, sleeps, eats, and functions. While these metrics are essential, they leave room for variability, misdiagnosis, and treatment mismatches. A structural indicator in the brain could complement traditional assessments, making precision psychiatry more than a dream.

“This study underscores the importance of multimodal assessments in MDD,” wrote the authors, “potentially contributing to the foundation of individualized clinical decision-making.” By combining brain imaging with psychological profiling, clinicians might one day predict who is most at risk for chronic depression and offer earlier, more targeted interventions.

Could Treatment Change the Brain?

One lingering question is whether the thinning of the PHC is a cause or consequence of depression. Does depression erode the PHC over time, or does a thinner PHC make someone more vulnerable to falling into depression in the first place?

There’s growing evidence that treatments—especially psychotherapy and certain medications—can induce structural changes in the brain. For instance, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, and even antidepressants have all been shown to increase cortical thickness in specific regions. If future studies confirm that PHC thickness can be restored or stabilized through treatment, this region could become a focus not just for diagnosis but also for tracking progress and recovery.

Toward a Future of Personalized Mental Health Care

This study opens a door—but it’s not the final word. Depression is a multifactorial condition, influenced by genes, environment, life experience, and biology. The parahippocampal cortex may be one of several regions involved in this intricate dance of vulnerability and resilience.

Still, the idea that a measurable, visible change in brain structure correlates with both a diagnosable mental illness and a personality trait is powerful. It suggests that mental health is not just a matter of feelings, but of architecture—of how our brains are physically built and how that construction shapes the way we experience the world.

As imaging technology improves and the understanding of brain-behavior relationships deepens, we may inch closer to a new era in psychiatry—one where objective measurements support subjective suffering, and where prevention, early intervention, and tailored treatments are no longer out of reach.

The Human Face of the Science

While cortical thickness may be measured in millimeters, the lives it affects are immeasurable. Behind every scan is a person: a teenager struggling to find joy in music they once loved, a parent navigating exhaustion masked as irritability, a retiree feeling inexplicably empty amid plenty. These findings matter because they bring hope—hope that one day, we’ll understand depression not just in metaphor but in mechanism.

The work of Nießen, Rajkumar, and their team offers a glimpse of that future. It reminds us that emotions are rooted in biology, and that treating the brain with the seriousness it deserves is not just science—it’s compassion in action.

As we continue the long and winding journey toward unraveling depression, perhaps this small patch of thinning tissue in the medial temporal lobe will serve as a beacon—a clue from the brain itself, whispering what words cannot fully say.

More information: Dominik Nießen et al, 7-Tesla ultra-high field MRI of the parahippocampal cortex reveals evidence of common neurobiological mechanisms of major depressive disorder and neurotic personality traits, Translational Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41398-025-03435-y