Long before sunseekers strolled the golden sands of Portugal’s Algarve coast, another set of footprints crossed those shores—left not by modern humans, but by Neanderthals. And these silent impressions, pressed into ancient dunes tens of thousands of years ago, are now telling a vivid story about how our distant cousins lived, hunted, and perhaps even taught their children by the sea.

A groundbreaking new study, led by geologist Carlos Neto de Carvalho of the University of Lisbon and the Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark, has unveiled some of the most compelling evidence yet that Neanderthals weren’t just occasional visitors to the ocean’s edge. They may have been seasoned coastal dwellers who made the beaches part of their hunting grounds—and part of family life.

Published in Scientific Reports, the research sheds fresh light on a species often stereotyped as cave-dwelling hunters of forests and mountains. Instead, it reveals Neanderthals as adaptable people who moved confidently across sand and surf.

Ancient Tracks Etched in Time

The story begins on the windswept shores of southern Portugal, where cliffs plunge into crashing Atlantic waves and sand dunes ripple under brilliant sunlight. Here, two sites—Praia do Telheiro and nearby Monte Clérigo—hold precious clues to the deep past.

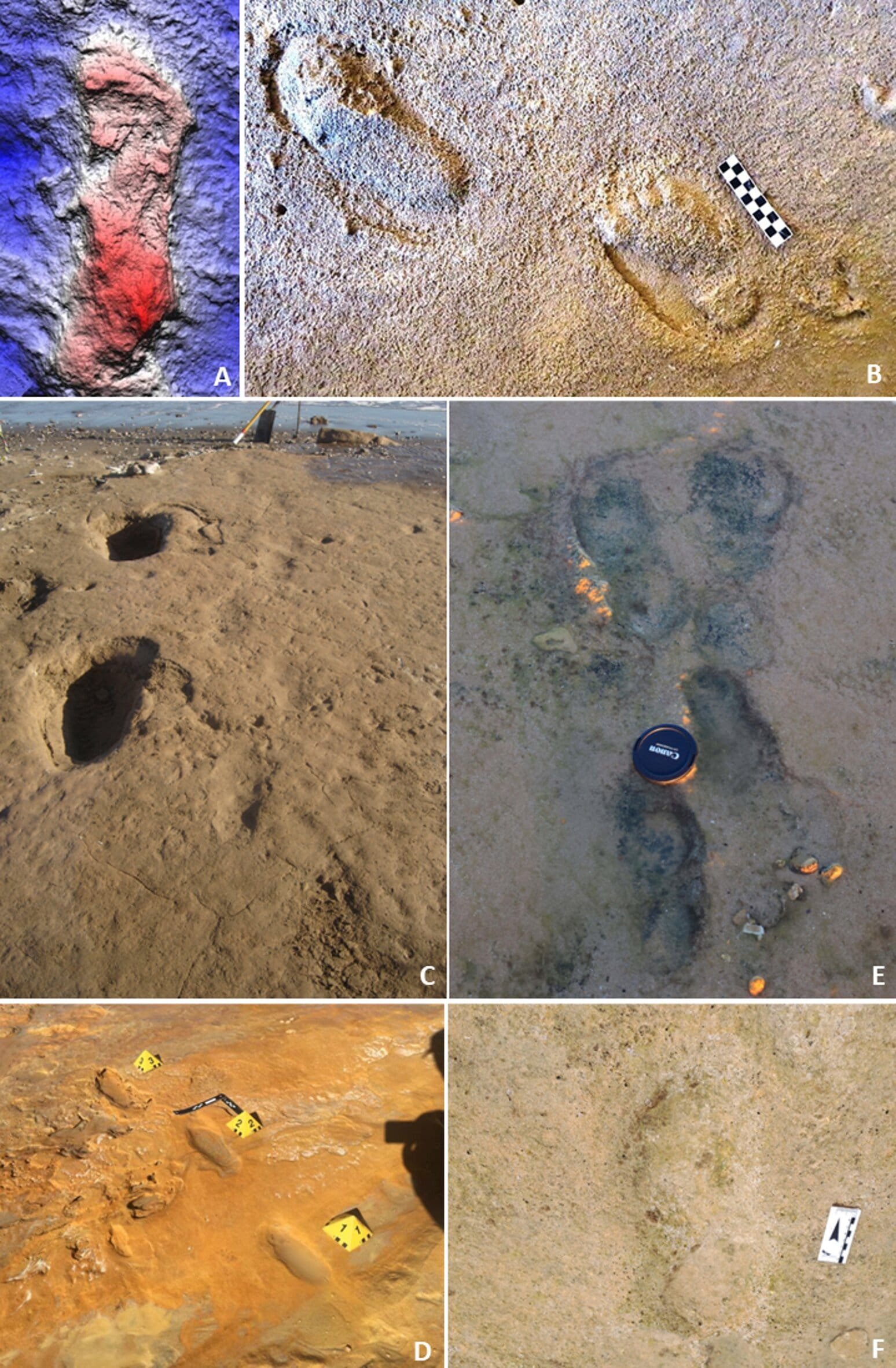

At Praia do Telheiro, a single footprint, pressed into what was once wet sand, has survived an astonishing 82,000 years. It’s a fleeting record—a solitary mark from a lone traveler on a Stone Age shoreline.

But it’s Monte Clérigo that delivers the most intimate scene. There, preserved under layers of sand for 78,000 years, lie ten footprints clustered together. The tracks tell of a small group moving across a dune: an adult male standing between 1.69 and 1.73 meters tall (about 5 feet 6 inches to 5 feet 8 inches), a child around 7 to 9 years old, and a toddler no older than two.

To pin down these ancient dates, scientists used a method known as Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL), which measures when minerals in the sand were last exposed to sunlight. The technique allowed the team to calculate the precise age of the track-bearing layers—offering confidence that the footprints truly belonged to the Neanderthals’ time.

The Hunt on Shifting Sands

Footprints are more than just impressions in stone; they’re echoes of life in motion. They tell us how tall ancient people were, how they walked, and, sometimes, what they were doing.

At Monte Clérigo, the scientists found more than human prints. Scattered around the Neanderthal tracks were the delicate hoofprints of red deer, etched into the same dune. To researchers, it’s tantalizing evidence that the Neanderthals were on the hunt.

“The uneven terrain of dunes provides excellent cover for stalking and ambushing prey,” the team wrote in their paper. Ridges and hollows break up sight lines, allowing hunters to slip closer without being seen. The presence of both deer and human footprints suggests a scene as dramatic as it is ancient: Neanderthals creeping through the dunes, children in tow, poised to strike at unsuspecting game.

Family on the Beach

The discovery raises a poignant question: Was the toddler part of the hunt—or simply along for the journey?

Though it’s impossible to know exactly what role each individual played, the footprints hint at a remarkable possibility—that Neanderthal hunting was sometimes a family affair. Children may have learned skills by watching adults track and stalk animals, absorbing lessons in survival from an early age.

“The body size of the footprints and the stride lengths help us estimate not only ages but also suggest these individuals were moving together,” explains Carlos Neto de Carvalho. “This gives us a rare glimpse into the social behavior of Neanderthal groups.”

It’s an image that challenges outdated notions of Neanderthals as brutish or unimaginative. Instead, it paints them as social, intelligent beings who integrated family life with the practical demands of survival.

Coasts as Lifelines

The Algarve discoveries add to a growing body of evidence that Neanderthals were adept at exploiting coastal resources. Archaeologists have uncovered shells, fish bones, and marine tools in Neanderthal sites from Gibraltar to Italy. These finds indicate they gathered shellfish, caught fish, and perhaps even used marine materials for tools and ornaments.

“This study provides the first direct evidence of Neanderthal activity on the Portuguese Atlantic coast,” the authors wrote. “It highlights their use of dune landscapes for movement and possibly hunting, and underscores the ecological diversity of their diet and behavior.”

Whether Neanderthals lived year-round by the sea or visited seasonally remains uncertain. But what’s clear is that coastal environments offered them rich resources: protein from marine life, fresh water, and strategic hunting grounds.

Echoes of the Ancient Shore

There’s something hauntingly beautiful about knowing that the same beaches where vacationers spread towels and children build sandcastles were once trod by Neanderthal families, alert for deer among the dunes.

In those footprints, we glimpse not only the physical presence of our ancient relatives but also the rhythms of their daily lives—their hunts, their migrations, and perhaps even the laughter of children running across the sand.

Seventy-eight thousand years later, the tide still rises and falls on Portugal’s shores. And hidden beneath the dunes lies the imprint of a people who, in many ways, were not so different from us.

Reference: Carlos Neto de Carvalho et al, Neanderthal coasteering and the first Portuguese hominin tracksites, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-06089-4