Long before humans etched history into stone, an invisible drama played out across plains and forests, where claw met hoof, and tooth tested hide. The outcome of that primal contest didn’t just determine who lived or died on a given day—it rewrote the very blueprint of life on Earth.

In two groundbreaking studies, scientists from Brazil’s State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) have illuminated how predator-prey interactions echoed through deep time, shaping the destinies of saber-toothed tigers and the once-spectacular diversity of North America’s antilocaprids—a family of swift-footed herbivores now represented by just one survivor: the American pronghorn.

Their findings reveal that these evolutionary fates weren’t merely victims of sudden ice ages or the arrival of spear-wielding humans. Instead, they were entangled in an ancient dance of pursuit and escape, competition and adaptation, that spanned millions of years.

Saber-Toothed Tigers: Death by Empty Plates

Few creatures stir the imagination like the saber-toothed cats, whose scimitar-like fangs once carved fear into the Pleistocene. But while textbooks often blame their downfall on the mass extinction of large animals at the end of the Ice Age, João Nascimento, lead author of the studies, discovered the story runs much deeper.

“One of the hypotheses that’s received the most attention was that the end of saber-toothed tigers could be linked to the extinction of megafauna between 50,000 and 11,000 years ago,” Nascimento explains. “These large animals became extinct due to climate change and human actions, and as a result, the predators were left without their main prey.”

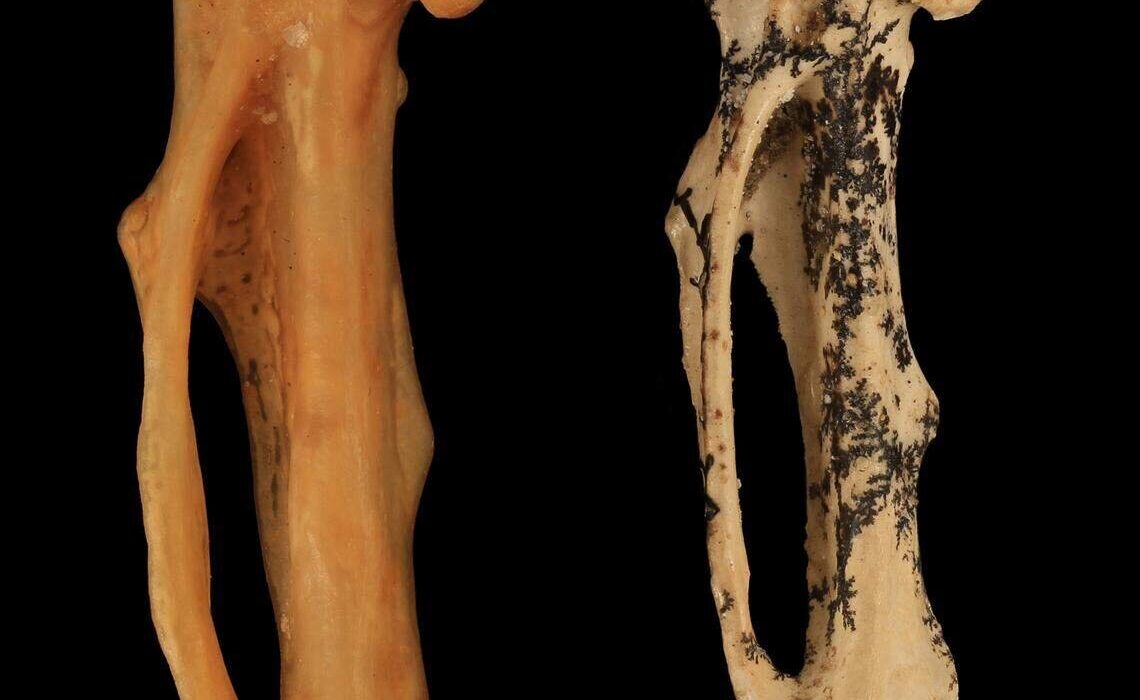

Yet, Nascimento’s analysis, published in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology, suggests the seeds of extinction were sown millions of years earlier.

Drawing on vast fossil databases from North America and Eurasia, the researchers reconstructed 20 million years of evolutionary history. They discovered that saber-toothed cats didn’t simply vanish in one catastrophic event—they were dwindling for ages, gradually losing species whenever prey diversity dropped.

Saber-toothed cats first appeared 14 million years ago in Eurasia and 12 million years ago in North America. At their zenith, eight species prowled the continents. But about six million years ago, their numbers began to decline, stabilizing at five species before their final extinction around 11,700 years ago.

Climate Change and the Shrinking Menu

While climate change alone didn’t directly doom these predators, shifting environments indirectly stacked the odds against them. Around six million years ago, Earth’s climate grew drier, transforming forests into open grasslands. Browsing herbivores, dependent on leafy forests, vanished, replaced by grazing species better suited for open plains.

“Our study did not find a direct relationship between this event and the reduction in saber-toothed cats,” says Mathias Pires, who supervised the work. “But these changes in the environment had an indirect impact on the extinctions of different saber-toothed species by reducing the availability of prey.”

Fewer prey species meant fewer opportunities for saber-toothed cats, whose specialized hunting style relied on bringing down large animals. As prey vanished, these apex predators were caught in a slow-motion ecological collapse.

Antilocaprids: The Vanishing Sprinters of North America

If the saber-toothed cats suffered from empty stomachs, another group faced death in the other direction: hunted to extinction.

In a second study published in Evolution, the team turned their attention to the antilocaprids—an ancient family of hoofed animals once as varied and abundant as Africa’s antelope herds. Today, only the American pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) remains, famed for reaching speeds near 100 km/h.

But this lone survivor hides a lost dynasty. The fossil record reveals a vibrant cast of characters: small forest dwellers, grazing plains runners, and everything in between.

One of the two subfamilies, Merycodontinae, vanished about six million years ago—the same time the saber-toothed cats began their decline. Coincidence? The researchers think not.

Merycodontinae were folivores, depending on forest habitats that disappeared under encroaching grasslands. Simultaneously, new competitors arrived: the proboscideans—the ancestors of modern elephants—who also coveted forest resources.

Yet for the surviving Antilocaprinae subfamily, another threat emerged: an explosion of predators.

Felids on the Hunt—and the Birth of Speed

About six million years ago, North America saw an increase in feline predators, including the American cheetah (Miracinonyx). Like its African cousin, this sleek cat was built for high-speed chases.

Other research has long proposed that the astonishing swiftness of the American pronghorn evolved as a desperate countermeasure to outrun such predators. The UNICAMP team’s new work offers compelling support: spikes in predator diversity coincided with dramatic reductions in antilocaprid diversity.

“Even in prehistory, the arms race between predator and prey played a decisive role,” Nascimento says. “We’re showing how an increase in predators can reduce the availability of prey, which in turn reduces the abundance of predators, and how this can manifest on an evolutionary scale.”

A Message From Deep Time

What makes these studies so significant is their scope. Instead of focusing on a single moment—like the ice ages or human arrival—the researchers tracked evolutionary arcs spanning continents and epochs. Fossil databases brimming with information about body sizes, diets, and ancient ecosystems allowed them to reconstruct these sweeping histories in astonishing detail.

Pires believes the lessons extend beyond paleontology. “It’s a warning about how we may be altering the future with the extinctions we’re causing now,” he says.

Predators and prey are bound in an eternal dance, each shaping the destiny of the other. As modern humans accelerate species losses, we risk destabilizing ancient relationships forged over millions of years.

The ghosts of saber-toothed tigers and vanished pronghorn kin remind us that extinction rarely comes in isolation. In nature, every disappearance echoes outward, rippling through time, shaping worlds yet unseen.

References: João C S Nascimento et al, Variation in prey availability over time shaped the extinction dynamics of sabre-toothed cats, Journal of Evolutionary Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1093/jeb/voaf043

João C S Nascimento et al, Open ecosystems expansion, competition, and predation shaped the evolution of Antilocapridae, Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1093/evolut/qpaf091