Long before the modern brain was even a spark in the tree of life, our ancestors scurried underfoot, hiding in shadows from tooth and claw. Over millions of years, through fire, blood, famine, and birth, those ancestors gradually developed the brains we now use to write poetry, fall in love, or ponder the meaning of the cosmos. But what if the mind we rely on today still bears the marks of those ancient struggles? What if our fears, desires, and moral judgments are not merely cultural quirks or psychological oddities—but the long shadows of evolutionary pressures that once decided life or death?

This is the central premise of evolutionary psychology: that the human mind is not a blank slate or random accident, but a product of natural selection. Just as our hands are shaped for grasping and our legs for walking, our minds are adapted for solving the problems faced by our ancestors in the environment in which they evolved. To understand human behavior, we must ask not only what the mind does, but why it does it—from an evolutionary perspective.

Evolutionary psychology bridges the gap between biology and the soul, between ancient instinct and modern identity. It proposes a thrilling, and at times unsettling, idea: that the key to understanding ourselves lies not just in therapy sessions or laboratory tests, but in the deep history of our species—the unforgiving forge of evolution that crafted the human mind.

From Darwin’s Insight to the Psychology of the Present

The roots of evolutionary psychology trace back to Charles Darwin himself. In The Descent of Man (1871), Darwin wrote not only about physical evolution but also about mental faculties. He speculated that emotions, moral instincts, and even the capacity for reason must have evolved by natural selection, just like any physical trait. But this idea was largely neglected by early psychologists, who were more focused on behaviorism or introspection than on biology.

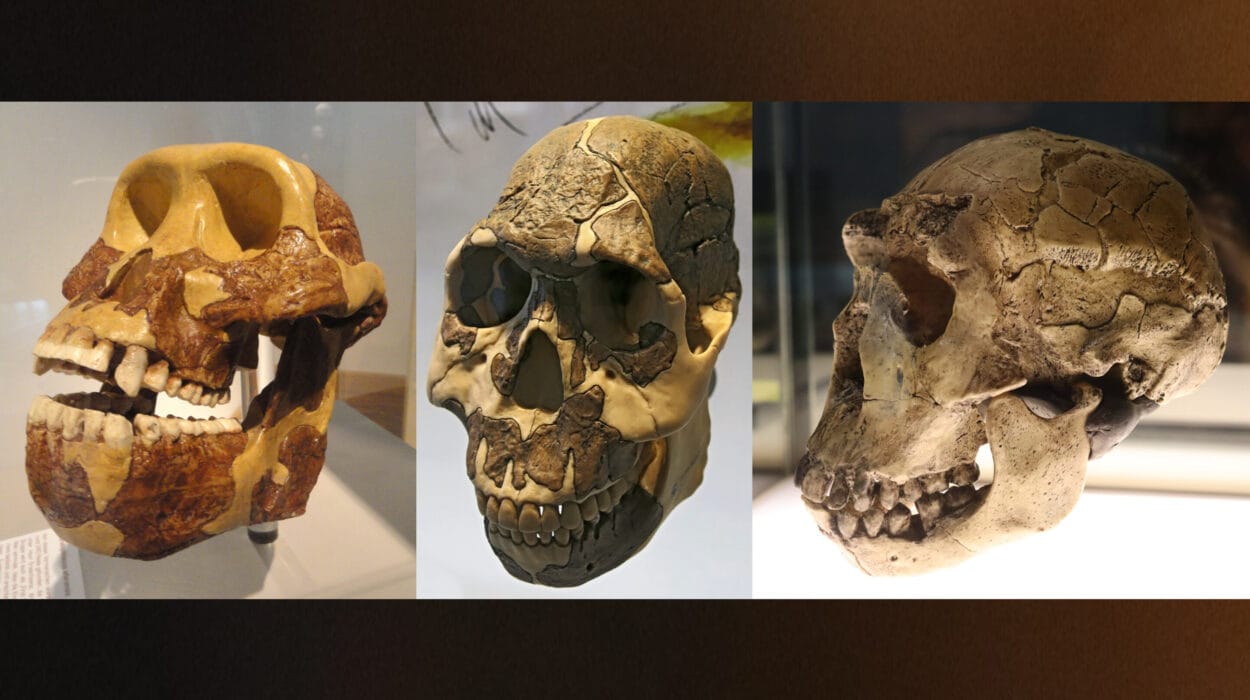

The modern rebirth of evolutionary psychology came in the latter half of the 20th century. As genetic research deepened and the study of animal behavior (ethology) blossomed, psychologists began to reconsider the idea that the mind might be a collection of evolved modules—each finely tuned to handle specific problems from our evolutionary past.

In the 1990s, a group of researchers including Leda Cosmides, John Tooby, and Steven Pinker helped crystallize evolutionary psychology as a distinct field. They argued that the brain is not a general-purpose problem solver, but a “Swiss army knife” of specialized mental adaptations. Each mental tool—jealousy, language, kin recognition, fear, cooperation—was shaped by natural selection to handle a different challenge faced by our hunter-gatherer ancestors during the Pleistocene epoch.

This period, often referred to as the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness (EEA), spanned millions of years. During that time, our ancestors lived in small nomadic groups, relied on foraging and hunting, faced constant threats from predators and rivals, and navigated complex social dynamics. The brain evolved under these conditions, and while our culture has changed dramatically since then, our brains have not had enough time to evolve away from those deep-rooted adaptations.

The Evolution of Emotion: Fear, Love, and Anger Revisited

Emotions may feel ineffable—flashes of joy, waves of rage, or pits of dread. But evolutionary psychology views them as functional. Emotions are not random; they are problem-solving mechanisms designed by evolution to promote survival and reproduction.

Take fear. It is not pleasant, but it can be lifesaving. Fear heightens awareness, focuses attention, prepares the body for action. Ancestral humans who were quick to feel fear in the presence of snakes, spiders, or strangers were more likely to survive and pass on their genes. This is why so many people today instinctively recoil at creatures that posed risks in the ancestral world, even if such fears are irrational in modern contexts.

Love, too, is deeply rooted. Romantic love promotes pair bonding, essential for raising offspring in species where parental care is crucial. Parental love ensures investment in offspring who are helpless at birth. Even jealousy, often seen as a negative emotion, can be adaptive—guarding against mate poaching or infidelity, which could reduce reproductive success.

Anger, meanwhile, may have evolved as a bargaining tool. If someone violated your rights or harmed your reputation in a tight-knit social group, anger signaled that you were willing to impose costs unless fairness was restored. It could deter future offenses and maintain cooperation within groups.

These emotional systems may not always work well in today’s world—our minds were built for a very different environment—but they make sense in light of our evolutionary past. Modern anxieties about public speaking or social rejection may feel disproportionate, but in ancestral times, being ostracized could mean death.

Sex and Selection: Mating Minds

Few areas of life are as shaped by evolution as sex and reproduction. Darwin himself was obsessed with this question, coining the term “sexual selection” to explain traits that couldn’t be accounted for by survival alone. The peacock’s tail, for example, may be a liability in terms of escape from predators, but its beauty signals genetic fitness to potential mates.

In humans, mating behavior is similarly complex and highly adaptive. Evolutionary psychologists have explored why men and women often exhibit different preferences, behaviors, and emotional reactions in the mating domain. The argument is not that all men or all women behave identically, but that certain patterns reflect differential reproductive challenges faced by each sex.

Because women invest more biologically in offspring—through pregnancy, nursing, and generally more parental care—they are more selective in choosing mates. They evolved preferences for partners who could provide resources, protection, and long-term commitment. Men, facing a different reproductive calculus, could potentially father many children with little investment, so there may be stronger evolutionary pressures favoring sexual variety and youth—signals of fertility.

These tendencies do not dictate behavior, but they shape desires and biases. Research shows that, on average, men report greater interest in casual sex and younger partners, while women place more emphasis on a partner’s status, ambition, and ability to invest.

Infidelity, jealousy, and mate guarding also reflect these dynamics. Evolutionary psychology explains why sexual infidelity tends to provoke more intense reactions than other betrayals—because it posed direct threats to reproductive success.

Again, these ancient instincts may clash with modern values. We live in a world of contraception, gender equality, and sexual fluidity, yet we are still piloted by brains designed for a time when reproduction was the central currency of success.

The Tribal Mind: Morality, Altruism, and War

Humans are profoundly social. We cooperate, empathize, gossip, punish, and bond. But why? In a world ruled by selfish genes, why do we sometimes sacrifice ourselves for others or uphold moral values?

Evolutionary psychology has proposed several powerful answers. Kin selection explains why we help our relatives: by aiding those who share our genes, we increase the chance those genes will persist. This logic, formalized in William Hamilton’s rule, shows that altruism can evolve if the cost to the helper is outweighed by the benefit to the recipient, multiplied by genetic relatedness.

But we don’t just help kin. We help strangers, build communities, enforce fairness. This suggests the operation of reciprocal altruism—a strategy where helping others can bring future benefits. Those who cooperate can build reputations and alliances, while cheaters are punished or ostracized.

This moral machinery may explain why we care so much about fairness, justice, and reputation. Our ancestors who upheld group norms were more likely to be trusted, included, and supported. Those who were seen as freeloaders or liars were excluded, reducing their chances of survival.

At the same time, the tribal mind has a dark side. We evolved in small groups competing with others for resources and territory. In-group loyalty and out-group hostility likely co-evolved. This helps explain nationalism, xenophobia, and the ease with which humans form “us vs. them” narratives.

Morality, in this view, is not a divine command or social construct alone—it is an adaptive toolkit for navigating the challenges of group living. We are moral because it helped our ancestors thrive in a social world.

Language and the Mind’s Theater

Language is one of the defining features of Homo sapiens. It allows us to share knowledge, express emotions, and coordinate actions. But it is also a mystery. How did such a complex system evolve? No other species has anything like it.

Evolutionary psychologists argue that language likely evolved as an adaptation for social living. In the ancestral environment, being able to communicate intentions, share warnings, tell stories, and build coalitions would have been a powerful advantage. Those who spoke well could lead, persuade, and bond with others.

Steven Pinker famously described language as an “instinct”—not learned from scratch but built into the brain. Children naturally acquire language even with limited exposure, and all human cultures develop language, suggesting a biological basis.

Language also shaped our ability to think. It allowed for abstract concepts, complex planning, and moral reasoning. The emergence of language may have accelerated cultural evolution, enabling the transmission of ideas across generations.

Importantly, our minds may be tuned for gossip, not pure logic. Theories suggest that human brains evolved to handle social information—who did what to whom, who can be trusted, who is part of which alliance. This explains our fascination with stories, our tendency to attribute motives, and our love of drama.

The Adapted Mind in a Modern World

If the human mind is a product of evolution, then it was not designed for skyscrapers, stock markets, or social media. It was built for a world of close relationships, immediate threats, and direct experience. This mismatch between ancient mind and modern world can explain many puzzles of human behavior.

Obesity, for example, can be understood as the result of evolved preferences for calorie-rich foods in a world where such foods were rare. Today, those preferences are hijacked by processed snacks and sugary drinks.

Phobias, too, often reflect ancestral dangers—snakes, heights, blood—even if modern threats like cars or electricity are far more deadly.

Our attention is drawn to gossip, celebrity, and conflict because these were critical in small-group dynamics. Social media, with its endless stream of likes, comments, and outrage, plays directly into ancient neural circuits evolved for social monitoring and signaling.

Understanding these mismatches does not excuse harmful behavior, but it can help us develop better interventions. By acknowledging our evolutionary roots, we can build systems that work with, rather than against, our cognitive architecture.

Criticisms and Cautions

Evolutionary psychology is not without controversy. Critics argue that some of its claims are speculative, unfalsifiable, or rely too heavily on “just-so stories.” Others caution against interpreting human behavior solely through the lens of biology, ignoring culture, learning, and context.

There is also the risk of misusing evolutionary arguments to justify inequality, sexism, or racism. These are misinterpretations. Evolutionary psychology seeks to explain behavior, not excuse it. The fact that a trait evolved does not mean it is desirable or immutable.

The field continues to evolve, incorporating findings from neuroscience, anthropology, genetics, and cultural studies. More sophisticated models now account for gene-environment interactions and the plasticity of human behavior.

Rediscovering Ourselves

In the end, evolutionary psychology offers a grand, unifying narrative—one that reconnects us with our ancestors and reveals the hidden logic behind our thoughts and emotions. It invites us to see the mind not as a mystery or a mistake, but as a survival machine honed over eons.

It asks us to look at love, laughter, envy, language, and leadership not as quirks of culture or quirks of fate, but as ancient adaptations playing out in the modern world. It reminds us that beneath our suits, our smartphones, and our sophistication, we are still running software written on the savannas of Africa.

And in understanding that software—not to be slaves to it, but to master it—we may come to understand not only who we are, but who we might become.