For decades, pterosaurs—those enigmatic, winged reptiles of the Mesozoic Era—have lived in our collective imagination as lords of the skies. With wingspans stretching to ten meters and silhouettes often mistaken for mythical dragons, they have captivated scientists and the public alike. But a groundbreaking study from the University of Leicester is painting a very different picture. It turns out that not all pterosaurs were exclusive aerialists; some of them were surprisingly at home on solid ground.

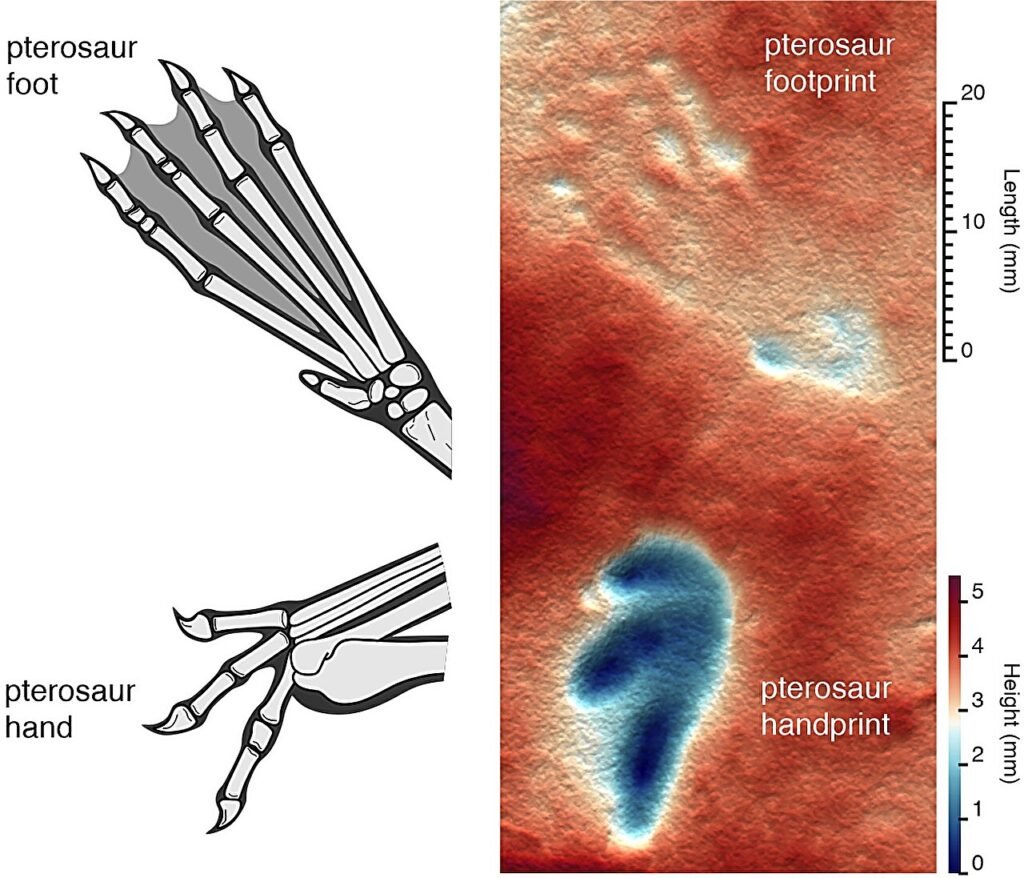

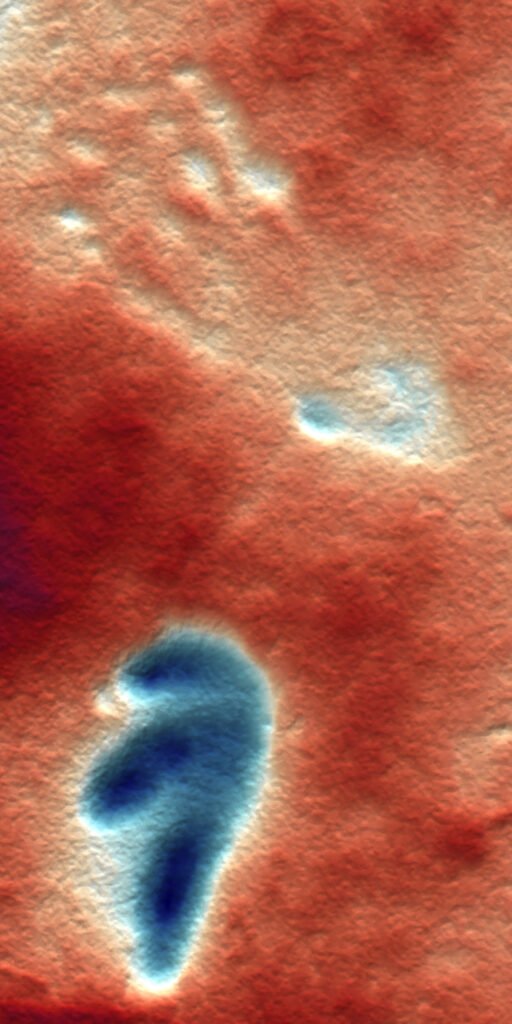

This revelation comes not from fossilized bones, but from something far more ephemeral and yet incredibly telling: ancient footprints. Over 160 million years old, these fossilized steps offer rare and intimate glimpses into the daily lives of pterosaurs. As it turns out, some of these ancient aviators spent just as much time walking as they did flying.

The Clues Beneath Their Feet

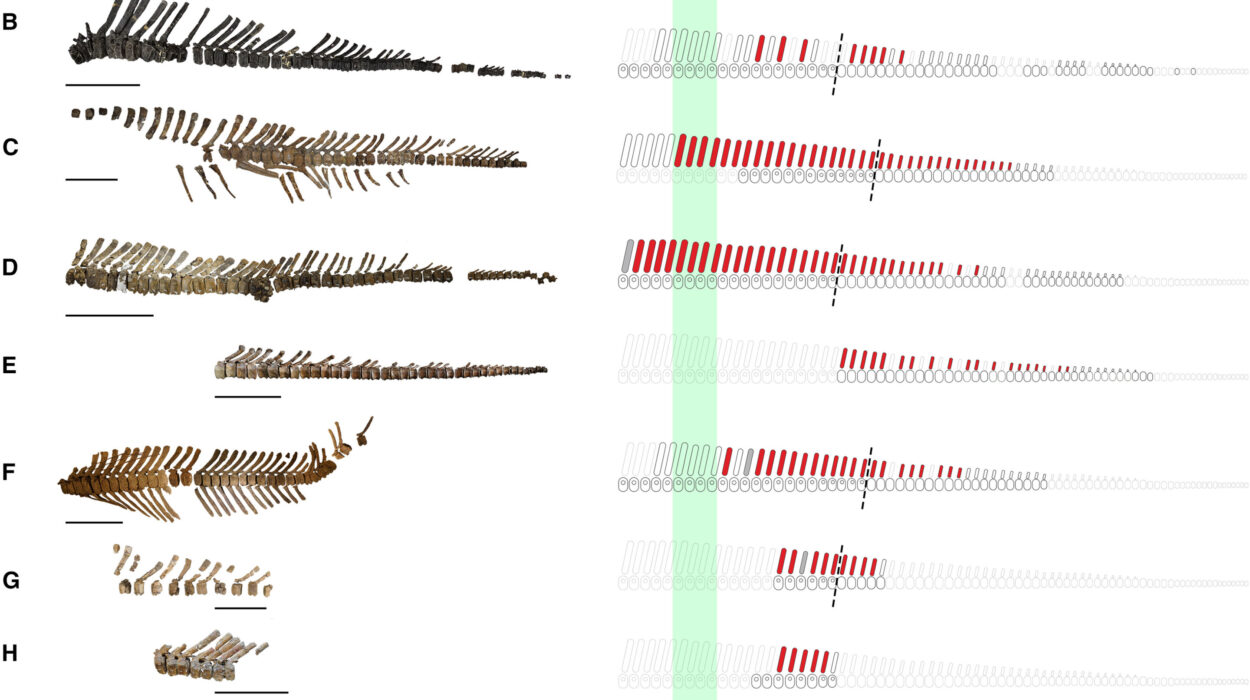

Published in Current Biology, the study by paleontologists at the University of Leicester is a culmination of years of meticulous analysis. Researchers used 3D modeling, detailed morphological comparisons, and a wealth of pterosaur skeletal data to solve a puzzle that has lingered for nearly a century: who exactly made these prehistoric footprints?

Three distinct types of pterosaur trackways were identified, each now matched with a specific group of pterosaurs. These matches aren’t mere guesswork; they are supported by close associations between tracks and fossilized skeletons found in the same rock layers. This breakthrough allows paleontologists to peer into the long-forgotten ecological habits of these magnificent animals.

“Footprints offer a unique opportunity to study pterosaurs in their natural environment,” explains lead author Robert Smyth, a doctoral researcher at the University of Leicester’s Centre for Paleobiology and Biosphere Evolution. “They reveal not only where these creatures lived and how they moved, but also offer clues about their behavior and daily activities in ecosystems that have long since vanished.”

Neoazhdarchians: The Giants on the Ground

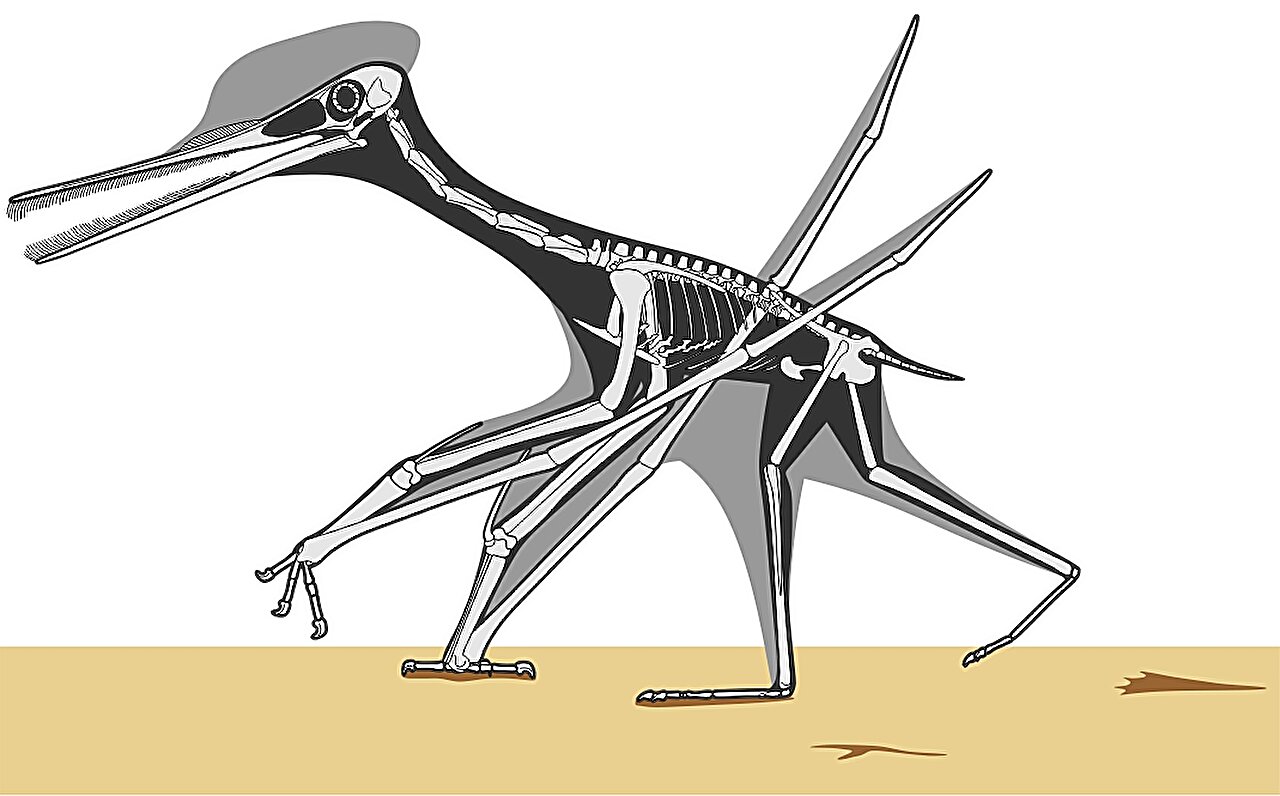

Perhaps the most astonishing revelation involves a group known as neoazhdarchians, which includes the colossal Quetzalcoatlus. With a wingspan rivaling a small airplane, Quetzalcoatlus is one of the largest known flying animals in Earth’s history. And yet, its story isn’t solely one of majestic flights across ancient skies.

Footprints attributed to neoazhdarchians have been found not only in coastal regions but also in deep inland environments around the world. These long-legged giants, it seems, spent considerable time walking, striding across beaches, plains, and riverbanks. Their broad, flat footprints indicate they were efficient terrestrial walkers—possibly stalking prey on land or scavenging like modern-day storks and marabou birds.

These prints persisted in the fossil record right up until the cataclysmic asteroid impact 66 million years ago. Alongside the dinosaurs, the neoazhdarchians vanished, but their footprints continue to speak across the eons.

Ctenochasmatoids: Waders of the Ancient Shores

A different set of tracks reveals the secrets of ctenochasmatoids, a group of pterosaurs known for their graceful, elongated jaws bristling with needle-like teeth. Their tracks are most commonly discovered in what were once muddy coastlines and shallow lagoons, suggesting a life spent wading rather than soaring.

These pterosaurs likely specialized in aquatic feeding. Picture them pacing along silty shores, their long beaks dipping into the water to snap up small fish or filter out tiny invertebrates. The abundance of their footprints in coastal deposits is a striking contrast to the relative scarcity of their skeletal remains. This imbalance suggests that while their bones were seldom preserved, these wading pterosaurs were abundant in their habitats.

Their footprints—delicate but surprisingly numerous—tell a story of life at the water’s edge, of specialized behavior, and of ecological niches occupied with subtle grace.

Dsungaripterids: The Shell-Crushing Striders

The third type of footprint unveiled by the Leicester team belongs to dsungaripterids, a group of pterosaurs that took terrestrial life to a new level. Characterized by robust limbs, powerful musculature, and unique dental arrangements, these creatures were well-adapted to life on the ground. Their beaks were toothless at the front but equipped with strong, rounded teeth further back—perfect tools for cracking open mollusks and shellfish.

Their tracks, often found in the same rock layers as their skeletons, offer compelling evidence of their behavior. Wide-gauge strides and deep impressions suggest deliberate, weight-bearing movement across firm substrates. Rather than flitting between cliffs, these pterosaurs may have roamed rocky coastlines or tidal flats, hunting for hard-shelled prey among the rocks.

Dr. David Unwin, a co-author of the study from the University of Leicester’s School of Museum Studies, remarked, “Finally, 88 years after first discovering pterosaur tracks, we now know exactly who made them and how.” This union of fossilized movement and physical form marks a significant advancement in understanding how these creatures interacted with their environments.

Beyond the Bones: A New Window into Pterosaur Life

Fossils of bones offer essential insights into anatomy and evolutionary relationships, but they are snapshots—static remnants of once-living organisms. Footprints, on the other hand, are dynamic. They capture a moment in time, a fleeting interaction between an animal and its environment. They can reveal speed, gait, posture, even mood.

“Tracks are often overlooked when studying pterosaurs,” Smyth emphasized, “but they provide a wealth of information about how these creatures moved, behaved, and interacted with their environments. By closely examining footprints, we can now discover things about their biology and ecology that we can’t learn anywhere else.”

The recognition of these three track types and their corresponding pterosaur groups is more than just a paleontological milestone. It hints at a major evolutionary shift during the middle Mesozoic. Around 160 million years ago, some pterosaurs began adapting more and more to life on land. This ecological diversification likely played a crucial role in their long-term success, allowing them to exploit a wide array of environments and resources.

The Broader Implications of Terrestrial Pterosaurs

The idea that pterosaurs were not merely aerial creatures, but also comfortable and competent ground-walkers, challenges longstanding assumptions. For decades, reconstructions of these animals often emphasized their flight capabilities while downplaying or ignoring terrestrial behavior.

But these footprints tell a richer, more nuanced story. They reveal pterosaurs not just as flyers, but as ecological generalists. Some soared, others stalked, waded, or strolled. They lived in coastal zones, inland plains, and possibly even forested regions. This new understanding invites paleontologists to reassess their place in ancient ecosystems—not as exclusive flyers, but as adaptable, versatile animals interacting with dinosaurs, mammals, and other prehistoric life.

The concept of pterosaurs as land-dwellers also raises fascinating questions about their social behavior. Did some species nest on the ground? Did they forage in groups, or defend territories on foot? These queries remain open, but thanks to the Leicester team’s research, scientists now have a powerful new framework for exploration.

A Paleontological Renaissance

The use of 3D modeling and comparative anatomy in this study represents the cutting edge of paleontological research. By combining traditional fieldwork with advanced digital tools, the University of Leicester team is part of a broader renaissance in paleontology. Fossil footprints, once seen as secondary curiosities, are now front and center in efforts to reconstruct prehistoric worlds.

These methods allow scientists to examine not just the shape of a footprint, but the angle of toe placement, the depth of impressions, the distance between steps—minute details that can unlock profound insights into movement and behavior.

As more footprints are unearthed around the globe, this approach could be extended to other prehistoric species as well. Dinosaurs, crocodiles, even early mammals—any animal that left its mark in mud or sand—might yield secrets about its life that bones alone cannot tell.

Echoes in Stone

In the end, what’s most compelling about this research is the intimacy it offers. Fossilized bones tell us that a creature was. But footprints tell us that a creature moved, that it acted in the world, that it lived. A footprint is a gesture frozen in time—a creature passing through, unaware that its step would outlive empires.

Thanks to the University of Leicester’s groundbreaking study, these ancient gestures have now found their voice. The pterosaurs, long pigeonholed as flying reptiles alone, are stepping into new roles as terrestrial beings—walking, wading, hunting, and living in a world far richer and more complex than we ever imagined.

And as paleontologists continue to follow their tracks through time, the story of life on Earth grows ever more vivid, dynamic, and wonderfully strange.

Reference: Identifying pterosaur trackmakers provides critical insights into mid-Mesozoic ground invasion, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.04.017. www.cell.com/current-biology/f … 0960-9822(25)00446-4