In a field in Suffolk, nothing about the surface suggested that history lay waiting beneath it. No towering ruins, no carved stones, no dramatic clues. Just soil, shaped by time and weather. And yet, buried within that ordinary ground was evidence of a moment that helped change what it means to be human. More than 400,000 years ago, someone stood there and made fire.

This discovery, led by a team of researchers from the British Museum, has pushed back the known origins of fire-making by an astonishing 350,000 years. Until now, the oldest confirmed evidence of humans making fire dated to around 50,000 years ago in northern France. What the Suffolk soil revealed instead was not borrowed flame from a lightning strike or a wildfire, but something far more profound: deliberate creation, careful control, and repeated use of fire by ancient people.

The site, known as Barnham, has now become one of the most important archaeological locations in the world. It does not merely tell us that fire was present. It tells us that fire was understood.

When Fire Became a Choice, Not a Gift

Long before this discovery, scientists knew that early humans encountered fire in nature. Sites in Africa suggest that natural fires were used more than a million years ago, likely scavenged from burning landscapes and carefully maintained. But relying on natural fire is very different from making it.

At Barnham, the evidence tells a new story. Here, humans were not waiting for fire to appear. They were creating it themselves.

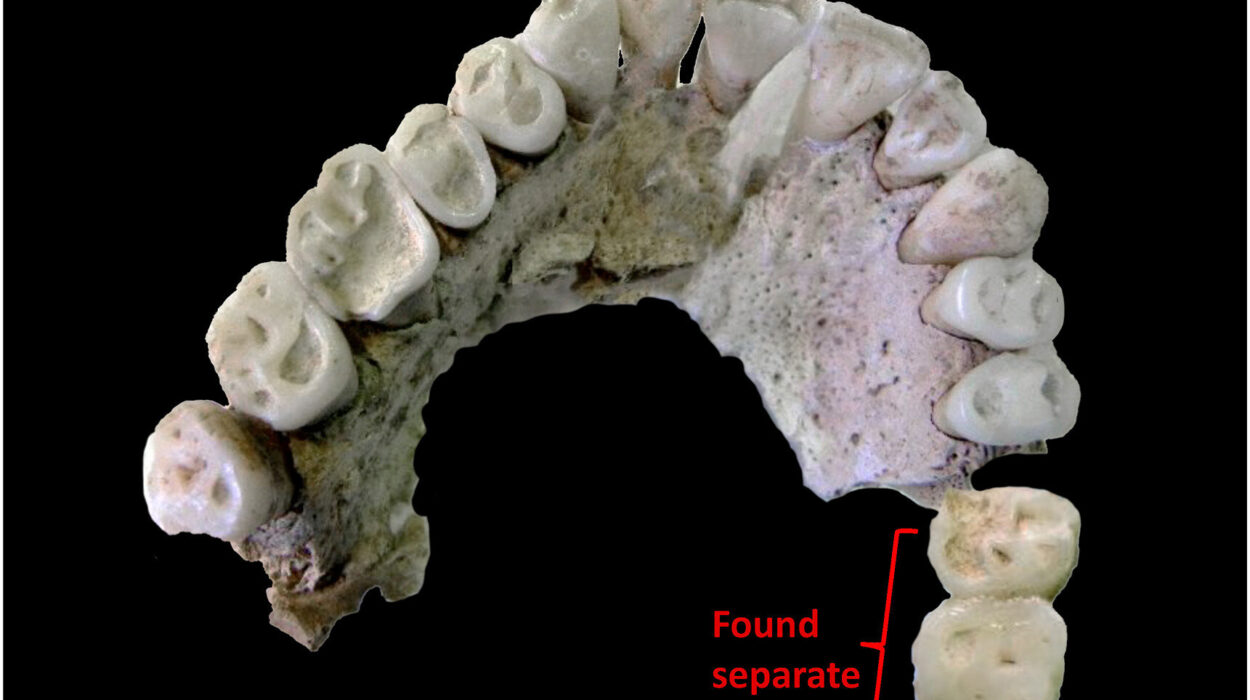

The remains are subtle but powerful. A patch of clay had been heated so intensely that its structure changed. Flint hand axes lay shattered by heat. Two small fragments of iron pyrite rested among the tools. Together, they formed a pattern that could not be explained by chance.

It took the research team four years to be certain. They had to rule out wildfires, soil chemistry, and natural discoloration. When geochemical tests revealed temperatures exceeding 700°C and signs of repeated burning in the same spot, the conclusion became unavoidable. This was a hearth. A campfire. A place where fire was made again and again.

Fire had become a choice.

The Spark That Changed Everything

The presence of iron pyrite may seem insignificant at first glance. It is just a mineral, dull and brittle. But in the hands of early humans, it held a secret. When struck against flint, pyrite produces sparks capable of igniting tinder.

Pyrite is rare in the area around Barnham. Its presence there means it was not stumbled upon accidentally. It was found elsewhere, recognized for its properties, and carried to the site intentionally. That act alone speaks volumes.

These early humans understood materials. They knew that flint could shape tools and that pyrite could coax fire into being. They knew where to find these materials and how to bring them together. This was not trial and error in the dark. It was knowledge passed on, practiced, and refined.

The researchers believe the evidence was probably produced by some of the oldest Neanderthal groups. At this point in time, human brain size was approaching modern levels, and behavior was becoming more complex. Fire-making was not an isolated trick. It was part of a broader transformation.

Proving Fire Where Fire Should Not Remain

Fire is fleeting. Ash blows away. Charcoal washes downstream. Heat fades, and time erases. This is why evidence of early fire use is so rare and why claims of ancient hearths are often debated.

At Barnham, survival itself became the clue. The heated clay endured. The flint cracked in recognizable patterns. The chemical signatures remained locked in the soil.

One of the key contributors to confirming this evidence was Dr. Sally Hoare from the University of Liverpool. Her work focused on the reddened sediments at the site, which could easily be misinterpreted. Red soil can be caused by fire, but it can also result from natural soil processes like iron oxidation.

Traditionally, archaeologists identify hearths through layers of reddened soil topped by ash and charcoal. But open-air sites like Barnham rarely preserve those neat signatures. Wind and water scatter them long before modern scientists arrive.

To overcome this, Dr. Hoare applied three scientific techniques to the soils and surrounding areas: soil micromorphology, archaeomagnetism, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon analysis. Together, these methods helped distinguish human-made fire from natural processes.

The results showed repeated heating in the same location, something wildfires do not do. Fire had been lit, extinguished, and lit again by human hands.

Voices From the Past, Echoed in the Present

For the scientists involved, the realization carried emotional weight as well as academic significance. Professor Ashton, Curator of Paleolithic Collections at the British Museum, described the moment with unmistakable pride.

“This is the most remarkable discovery of my career, and I’m very proud of the teamwork that it has taken to reach this ground-breaking conclusion. It’s incredible that some of the oldest groups of Neanderthals had the knowledge of the properties of flint, pyrite and tinder at such an early date.”

Dr. Hoare emphasized just how far-reaching the findings are.

“These findings suggest that humans at Barnham actively created their own fires. The presence of pyrite fragments at Barnham is the earliest known evidence of strike-a-light technology. This discovery extends the chronology of fire-making technology by approximately 400,000 years and establishes Barnham as a key global reference point for the earliest known fire-making practices.”

Dr. Davis, Project Curator: Pathways to Ancient Britain at the British Museum, captured the broader implications.

“The implications are enormous. The ability to create and control fire is one of the most important turning points in human history with practical and social benefits that changed human evolution. This extraordinary discovery pushes this turning point back by some 350,000 years.”

Fire as Freedom

Fire-making changed more than daily routines. It changed where humans could live and how they could survive.

Before fire could be made on demand, people were tied to places where natural flames existed. Once fire became portable knowledge rather than a fragile resource, humans gained freedom. Campsites could be chosen rather than inherited. Fire no longer needed constant tending; it could be re-ignited when needed.

With fire came warmth, protection, and light. Cold environments that once posed deadly risks became manageable. Nighttime dangers receded as flames pushed back darkness and predators alike. Humans could spread into harsher landscapes and survive there.

Fire also transformed food. Cooking made roots and tubers safer by removing toxins. Meat became less dangerous as pathogens were destroyed. Cooking softened food, making it easier to chew and digest. This freed energy from the gut and redirected it to the brain.

Over time, this energy shift supported cognitive development. Better nutrition enabled larger, more complex social groups. Shared meals around a fire became moments of connection, learning, and cooperation.

A Rare Window Into a Vanishing Past

Between 500,000 and 400,000 years ago, archaeological sites in the U.K., France, and Portugal suggest that fire was becoming increasingly important to early humans. What those sites lacked was an explanation for how that change occurred.

Barnham provides that missing link. It shows not just the use of fire, but the invention of fire-making.

The rarity of such evidence cannot be overstated. Fire leaves few lasting traces, and even when traces survive, proving human involvement is extraordinarily difficult. That is what makes the Barnham site exceptional. It preserves a fragile moment when knowledge crossed a threshold and reshaped the future.

The findings have been published in the journal Nature, placing Barnham firmly at the center of global discussions about human evolution.

Why This Discovery Matters

This discovery matters because it changes the timeline of humanity’s most transformative skill. Fire-making is not just another technological step. It is a foundation upon which culture, biology, and society were built.

By pushing the origins of fire-making back more than 400,000 years, the Barnham evidence reveals that ancient humans were capable of complex planning, material knowledge, and repeated technological action far earlier than previously believed. It shows that some of the oldest Neanderthal groups were innovators, not merely survivors.

Fire reshaped diets, expanded habitats, strengthened social bonds, and fueled brain development. It allowed humans to step beyond the limits imposed by climate and daylight. It was the difference between enduring the world and shaping it.

In a quiet field in Suffolk, the ground preserved a memory humanity almost lost. That memory tells us that long before written language, long before cities or tools of metal, someone struck flint against pyrite and watched sparks catch. In that moment, humans did not just warm themselves. They lit the path forward.

More information: Rob Davis et al, Earliest evidence of making fire, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09855-6