They were not aimless wanderers. Long before paved roads, GPS, or even Homo sapiens’ global reign, Neanderthals were mapping the wild heart of Eurasia—one river, one valley, one season at a time. Now, in a stunning new study, scientists have charted the likely routes these ancient humans took on a journey that stretched across 2,000 miles and nearly two millennia, revealing an unexpectedly efficient migration across some of the most formidable landscapes on Earth.

For decades, archaeologists puzzled over how Neanderthals—stocky, strong, and adapted to cold—managed to traverse the vast expanse from Eastern Europe to Central and Eastern Eurasia. While genetic evidence has long hinted at a second major migration event between 120,000 and 60,000 years ago, the physical trail was conspicuously absent. Between the scattered bones in Europe and Siberia’s archaeological remains lay a vast silence—a gap without campsites, tools, or hearths. How did they get there? And why?

Now, a team of anthropologists led by Emily Coco and Radu Iovita believes they’ve filled in that missing map, not with shovels and spades, but with code, climate data, and a supercomputer.

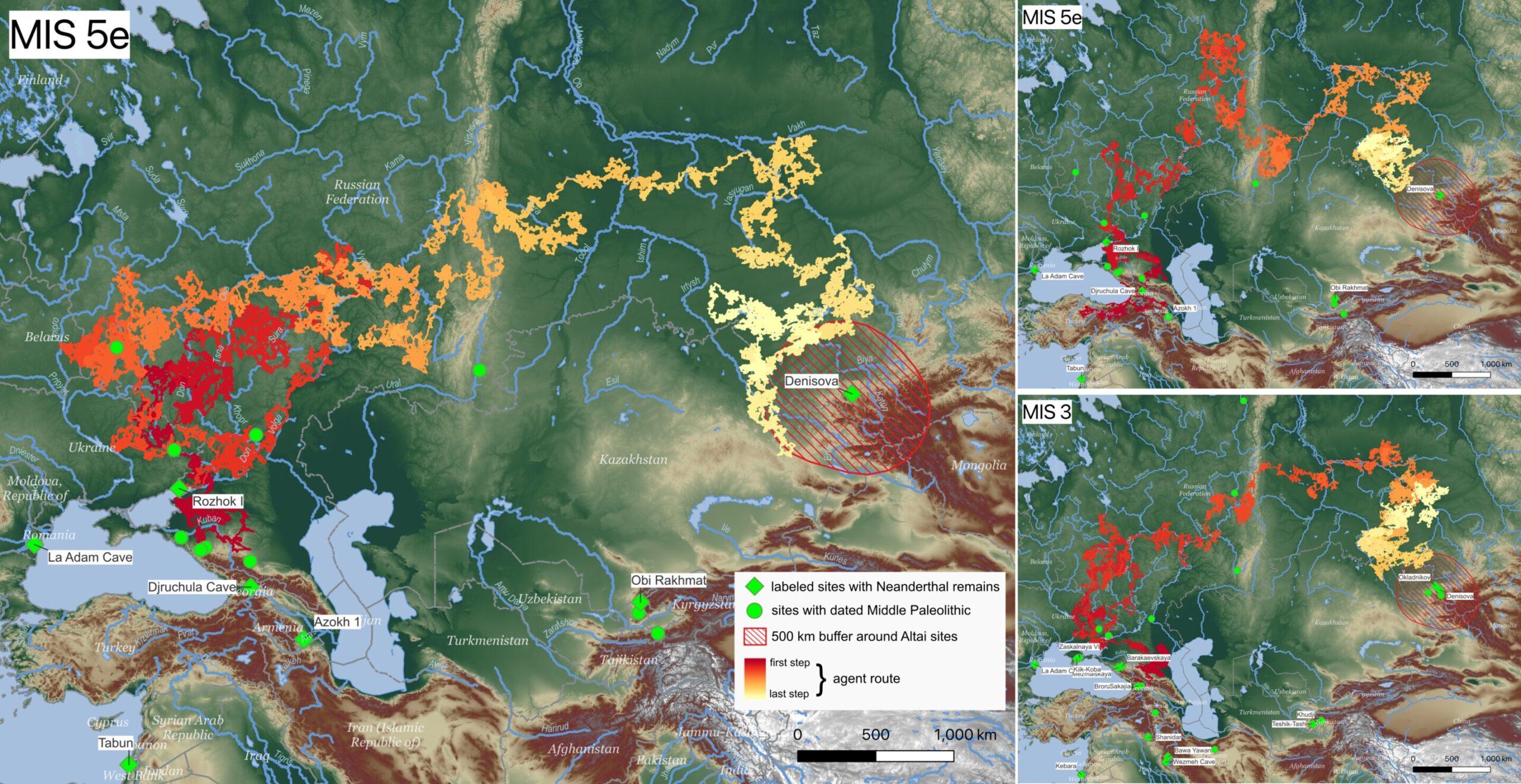

Published in PLOS One, their groundbreaking study simulates ancient Neanderthal movements through reconstructed Ice Age environments, revealing that these archaic humans likely followed river valleys like highways and waited for warmer interglacial periods to begin their epic migration. Their digital footprints, born of climate reconstructions and terrain modeling, trace winding paths through the Ural Mountains and southern Siberia—right into territory already occupied by the mysterious Denisovans.

Ancient Routes Through a Living Landscape

To walk in a Neanderthal’s footsteps, Coco and Iovita had to reconstruct a world long gone. That meant modeling topography, prehistoric rivers, ice sheets, and ancient temperatures—variables that shaped whether a group could cross a mountain pass, drink from a stream, or find enough game to survive.

Using the NYU Greene Supercomputer Cluster, the researchers recreated what Eurasia looked like during two warm periods in prehistory: Marine Isotope Stage 5e (around 125,000 years ago) and Marine Isotope Stage 3 (around 60,000 years ago). These were moments of respite between glacial advances—windows of time when the icy grip of the Ice Age loosened, and the earth softened enough to permit long-distance travel.

It turns out Neanderthals were excellent opportunists.

“Despite obstacles like mountains and large rivers, Neanderthals could have crossed northern Eurasia surprisingly quickly,” says Coco, who began the research as a doctoral student at New York University and now works at Portugal’s University of Algarve. “Our models show it’s entirely plausible that Neanderthals made it to the Siberian Altai in under 2,000 years, using multiple possible routes—all of which aligned with known archaeological sites.”

These routes weren’t haphazard. The simulations show a clear preference for river valleys—natural corridors that offered water, game, and relative ease of movement through a rugged terrain. It’s a strategy still used by modern humans and animals alike, from elk in the Rockies to nomads on the Mongolian steppe.

“Neanderthals could have migrated thousands of kilometers from the Caucasus Mountains to Siberia by following river corridors,” says Iovita, an associate professor at NYU’s Center for the Study of Human Origins. “Our simulations show that such migrations were not only possible—they were likely.”

A Chance Encounter with the Denisovans

These modeled routes don’t just connect sites—they connect species.

One of the most tantalizing implications of the study is how it aligns with genetic evidence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and Denisovans, another archaic human group that inhabited parts of Central and East Asia. The migration paths suggested by Coco and Iovita bring Neanderthals directly into Denisovan territory, particularly in the Altai region of Siberia, where remains of both species have been found in the same cave—Denisova Cave.

This convergence isn’t just geographical. It’s biological.

DNA extracted from ancient fossils has already revealed that Neanderthals and Denisovans interbred, leaving behind a complex genetic legacy that lives on in some modern humans, especially those of Asian and Oceanian descent. The newly reconstructed migration routes provide the first detailed environmental explanation for how such encounters might have occurred.

“Others have speculated on the possibility of this kind of fast, long-distance migration based on genetic data, but this has been difficult to substantiate due to limited archaeological evidence in the region,” Iovita notes. “Now, based on detailed computer simulations, it appears this migration was a near-inevitable outcome of landscape conditions during past warm climatic periods.”

Technology Meets Deep Time

What makes this study remarkable is not only what it tells us about Neanderthals—but how it tells us.

The idea of ancient humans using river valleys to migrate isn’t new. What is new is the precision with which this theory has been tested. Using agent-based modeling, a technique common in animal behavior and climate research but rarely applied to human evolution, the team was able to simulate individual decisions—where to go, what to avoid, how to respond to barriers like glaciers or steep terrain.

This human-focused modeling approach represents a major leap in how anthropologists can study the past. Instead of relying solely on rare bones or tools, researchers can now build dynamic, data-rich reconstructions of how ancient humans may have moved through the world—even in places where the physical trail has been erased by time.

“These findings provide important insights into the paths of ancient migrations that cannot currently be studied from the archaeological record,” Coco explains. “Computer simulations can help uncover new clues about ancient migrations that shaped human history.”

Rewriting the Story of Neanderthals

For decades, Neanderthals have lived in the public imagination as brutish, slow-moving relics of a primitive past. This image, however, has been crumbling under the weight of scientific discovery. We now know they made art, buried their dead, used complex tools, and interbred with modern humans. Now, we can add one more accolade: they were skilled long-distance travelers.

The idea that these ancient humans could cover vast distances across forbidding landscapes in just a few dozen generations changes how we understand not only their adaptability, but also their role in the human story. Far from being confined to isolated pockets in Europe, Neanderthals were explorers—capable of expanding their range with surprising speed and efficiency.

And they weren’t alone. Their journeys brought them face-to-face with other humans—cousins from a shared evolutionary tree—sparking interactions that would ripple through the genome of humanity for millennia to come.

A Map of Ancient Memory

In the end, this study doesn’t just chart a migration. It tells a story of survival, innovation, and connection—of how the rise and fall of glaciers shaped the destinies of entire species. It reminds us that deep time is not empty time. Even in an Ice Age, life moved. People moved.

They followed the rivers, crossed the mountains, and left behind more than bones and tools. They left questions—questions we’re only now beginning to answer with the power of technology, creativity, and a reverence for the human journey.

From the banks of ancient rivers to the servers of supercomputers, their story flows on.

Reference: Emily Coco et al, Agent-based simulations reveal the possibility of multiple rapid northern routes for the second Neanderthal dispersal from Western to Eastern Eurasia, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0325693