Around 66 million years ago, a mountain-sized asteroid slammed into the Yucatan Peninsula, igniting a global firestorm and casting a shroud of dust that blocked the sun. The resulting chaos wiped out roughly 75% of all species on Earth, most famously the dinosaurs. For decades, scientists believed that the ammonites—elegant, tentacled mollusks housed in spiral-shaped fossils—met their end during this same K-Pg (Cretaceous-Paleogene) boundary catastrophe. Closely related to the modern octopus and squid, these coiled-shell creatures were thought to have vanished the moment the world went dark. But a new investigation into the white cliffs of Denmark suggests that the history of life’s greatest comeback may need to be rewritten.

The Secrets Written in Stone

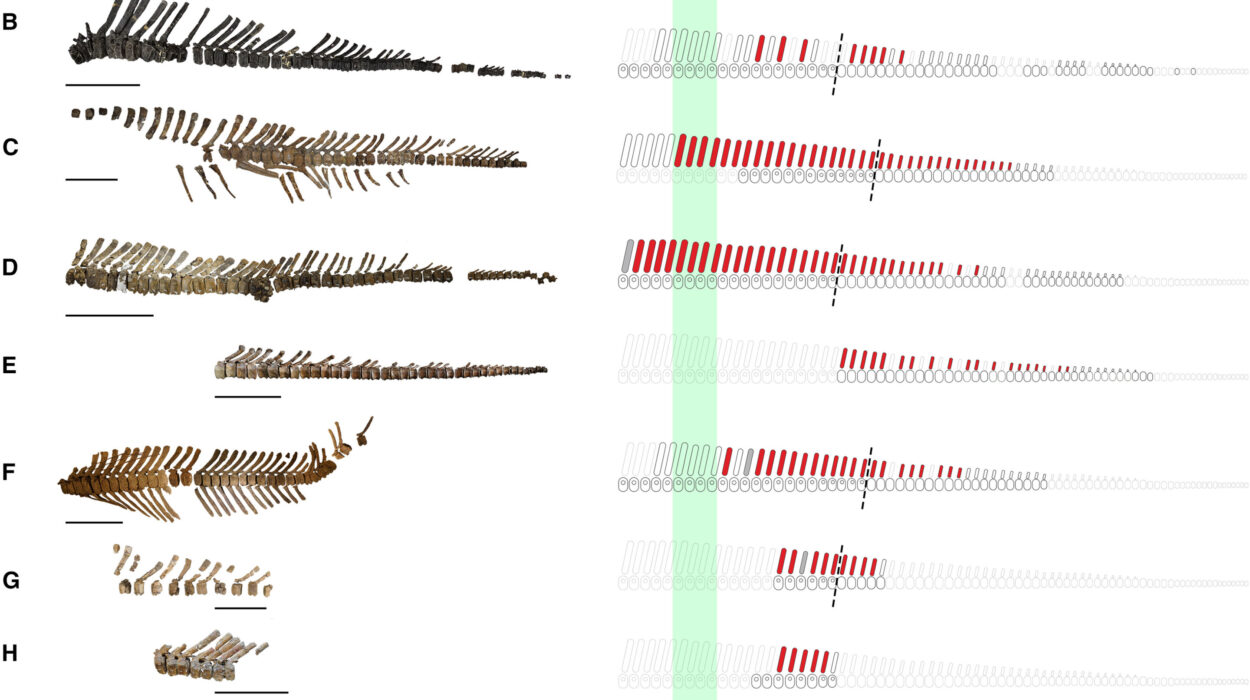

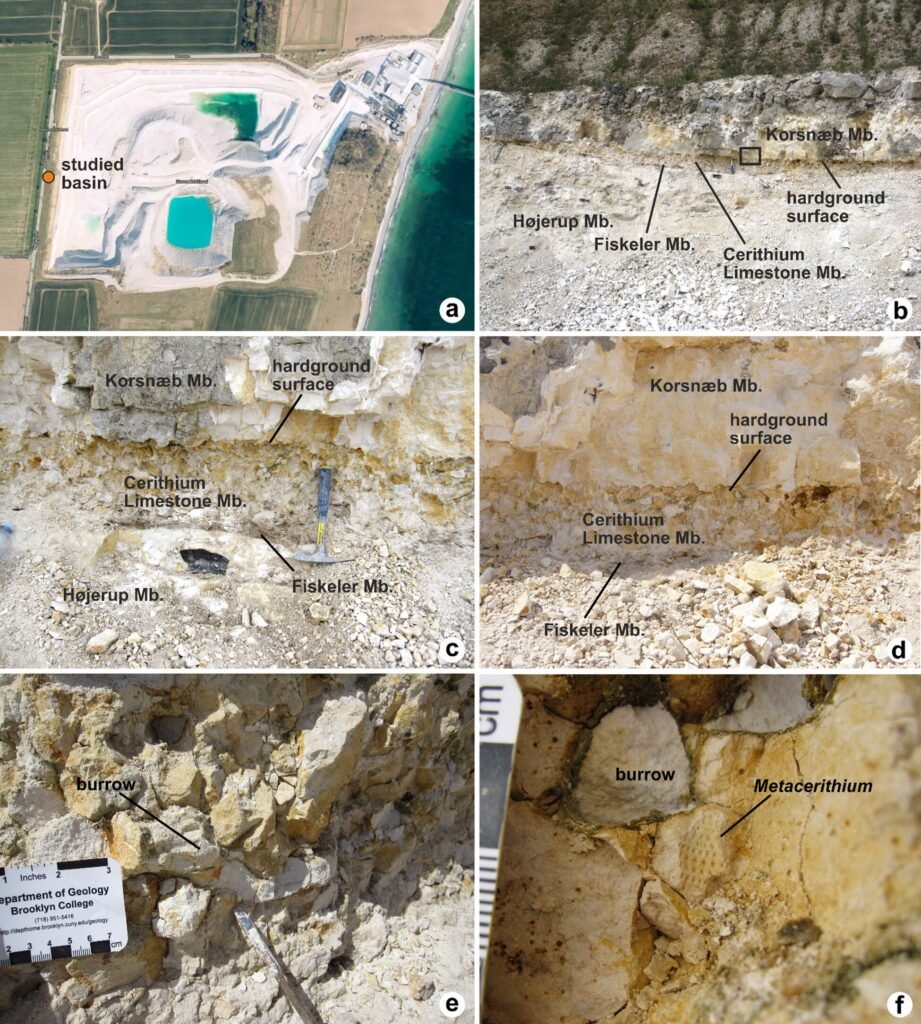

The story of this scientific detective work begins at Stevns Klint, a jagged, 15-kilometer-long coastal cliff that stands as a silent witness to Earth’s most violent transition. This UNESCO World Heritage Site is famous among geologists because it contains a visible, undeniable line in the rock that marks the exact moment the asteroid hit. Below the line lies the Cretaceous world of giants; above it lies the Danian period, the dawn of the Paleogene and the age of mammals. While exploring these heights, Professor Marcin Machalski and his colleagues from the Polish Academy of Sciences discovered something that shouldn’t have been there: ammonite fossils resting in the layers above the extinction line.

In the world of paleontology, finding a fossil in the “wrong” layer creates an immediate puzzle. Sometimes, an older fossil is eroded out of ancient sediment and washed into a younger layer of rock, a phenomenon researchers call a zombie fossil. These are remnants of the dead that appear to be younger than they actually are. To determine if these Danish ammonites were true survivors or merely stony ghosts from the past, the team had to look closer than anyone had before. They needed to know if these creatures were actually breathing and swimming in the post-extinction sea, or if their shells had simply been tossed into the mud millions of years after they died.

Looking Through the Microscopic Lens

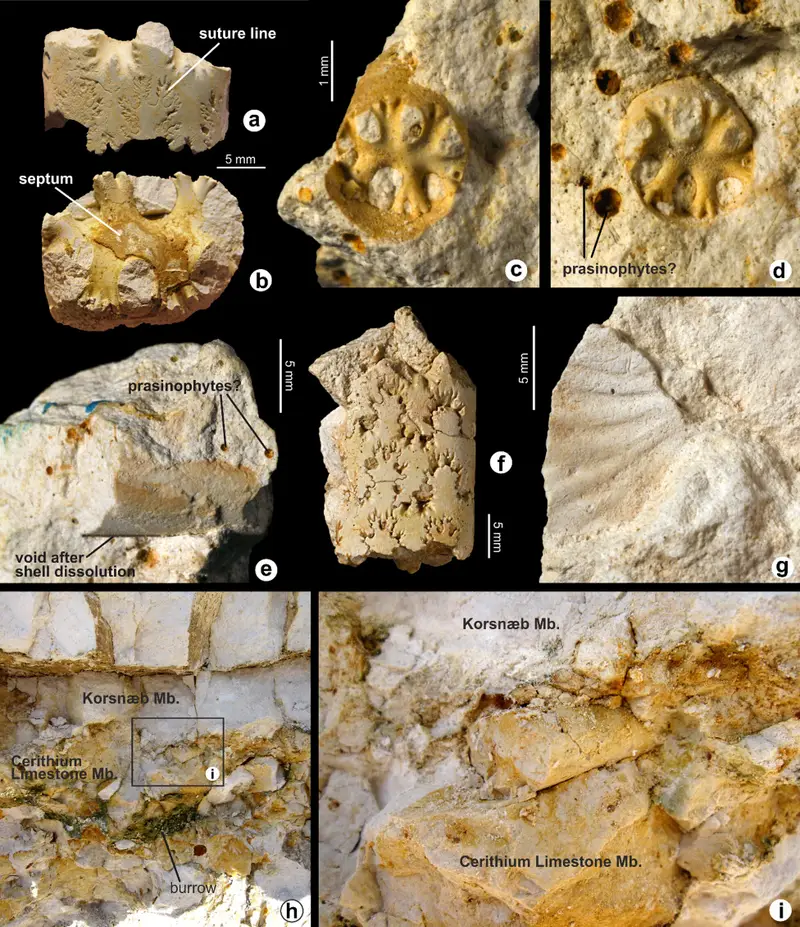

To solve the mystery, the researchers turned to a specialized technique known as microfacies analysis. This process involves using high-powered microscopes to peer into the very fabric of the stone. The team wasn’t just looking at the shape of the shells; they were inspecting the microscopic makeup of the sediment trapped inside them. By comparing the “filling” of the shells with the rock layers surrounding them, they could determine the exact environment where the ammonites finally came to rest. It was a forensic investigation of a cold case 66 million years in the making.

The results under the microscope were startling. Inside the fossilized shells, the researchers found a wealth of sponge spicules—tiny, microscopic spikes that served as the structural skeletons of ancient sponges. These spicules are a hallmark of Danian limestone, the rock formed after the mass extinction. Even more telling was what the researchers didn’t find. The shells contained almost no bryozoans, the tiny “moss animals” that were incredibly common in Cretaceous chalk but became rare in the Danian period. Because the mud inside the shells matched the post-extinction environment rather than the world of the dinosaurs, the evidence pointed to a radical conclusion: these ammonites were actually alive and thriving in the aftermath of the Great Dying.

The Ghostly Survivors of a Ruined World

This discovery suggests that the Cerithium Limestone fauna—the specific group of ammonites found at Stevns Klint—managed to navigate the immediate fallout of the asteroid impact. While the world was struggling to recover from a global winter and collapsing food chains, these resilient mollusks were still pulsing through the water, their long tentacles trailing behind their coiled homes. If the findings are accurate, they confirm that these marine creatures survived into the earliest part of the Paleogene, effectively cheating death while their dinosaur contemporaries disappeared forever.

However, proving they survived the initial blast only creates a deeper, more haunting mystery. Previous research has hinted that some populations of these creatures may have hung on for as long as 68,000 years after the asteroid hit. If the most famous extinction event in history wasn’t enough to kill them, the scientific community is left with a glaring question: what finally did? The study authors are now looking beyond the asteroid, wondering what environmental shifts or biological hurdles eventually brought the long lineage of the ammonites to a final, silent close.

Why the Final Chapter Matters

Understanding how species survive or succumb to global catastrophes is vital for piecing together the history of our planet. This research matters because it challenges the “instantaneous” nature of mass extinctions, showing that life is often more resilient and complex than a single catastrophic event. By proving that the ammonites survived the K-Pg boundary, scientists are forced to look more closely at the Danian period to understand the long-term recovery of the oceans. It reminds us that the end of an era is rarely a clean break; instead, it is a messy, lingering transition where some ancient travelers continue to swim through the ruins of their world, leaving behind clues for us to find millions of years later.

Study Details

Marcin Machalski et al, Ammonite survival across the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary confirmed by new data from Denmark, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-34479-1