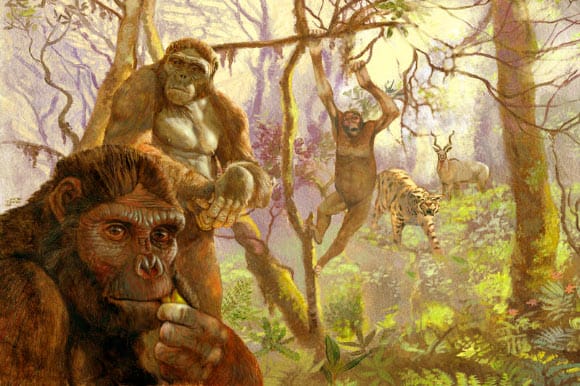

In a time before the first dinosaurs, nearly 445 million years ago, Earth was a world of vast, shallow seas and warm, greenhouse temperatures. The southern supercontinent, Gondwana, sat at the heart of a planet where life was defined by the strange and the gargantuan. Massive nautiloids with pointed shells reaching five meters in length drifted through the depths, while human-sized sea scorpions and armor-plated trilobites patrolled the seafloor. Among them snaked the conodonts, eel-like creatures with large eyes and tooth-lined throats.

In this crowded marine theater, our own ancestors—the gnathostomes, or jawed vertebrates—were little more than a footnote. They were humble, rare, and lived in the shadows of more successful, jawless giants. However, a series of planetary catastrophes was about to flip the script of evolution, clearing the stage for these minor players to become the protagonists of the modern world.

The Great Deep Freeze and the Rising Tide of Sulfuric Death

The stability of the Ordovician period came to a violent end during a geological blink of an eye. Researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) have mapped out how a massive environmental shift, known as the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction (LOME), decimated the planet’s inhabitants. The disaster struck in two distinct pulses.

First, the Earth’s climate plummeted from a greenhouse state into a sudden icehouse climate. Glaciers marched across Gondwana, locking up the planet’s water and drying out the shallow coastal seas like a sponge. This habitat loss was a death sentence for the majority of marine life. Millions of years later, just as the survivors began to adapt to the cold, the climate flipped back. The ice caps melted, drowning the seas in warm water that was tragically oxygen-depleted and laced with sulfuric chemicals.

By the time the chemistry of the ocean stabilized, about 85% of all marine species had vanished. The trilobites and giant mollusks were devastated, and the once-dominant jawless vertebrates were pushed to the brink. This biological havoc created a void—an empty world waiting for a new ruler.

A Secret Sanctuary in the South China Refugia

While the open oceans became graveyards, small pockets of life endured in refugia—isolated biodiversity hotspots separated by deep, impassable waters. By analyzing a database spanning 200 years of paleontology, the OIST team identified that these sanctuaries were the crucibles of modern vertebrate life. One such refuge was located in what we now know as South China.

In these stable, geographically small areas, the surviving gnathostomes were essentially trapped. However, this confinement was a blessing in disguise. With the previous kings of the sea—the conodonts and large arthropods—gone, the ecosystem was full of “open slots.” Much like Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands, which evolved different beak shapes to exploit different food sources, these early jawed fishes began to diversify rapidly.

The researchers found that the gnathostomes didn’t evolve jaws specifically to create new roles; rather, they stepped into the empty roles left behind by the dead. In the safety of the South China refugia, they evolved into the first full-body jawed fishes related to modern sharks. They spent millions of years refining their biology until they finally developed the strength and ability to cross the open ocean and colonize the rest of the globe.

The Inevitable Cycle of the Diversity Reset

This research reveals that evolution often follows a diversity-reset cycle. Rather than starting from scratch with entirely new ecological designs, nature tends to rebuild the same structures using different materials. The jawed vertebrates reconstructed the same complex food webs that existed before the extinction, but they did so with new species and functional designs that would eventually lead to all modern backboned animals.

While their jawless relatives continued to evolve in parallel for another 40 million years, the gnathostomes had already secured their advantage within the refugia. The study shows a clear trend: the pulses of mass extinction led directly to an explosion of speciation after several million years. By tracing the movement of these species across the globe, scientists can now see the exact moment when our ancestors stopped being background characters and started their journey toward global dominance.

Why This Ancient Survival Story Matters

This research fundamentally nuances our understanding of how life on Earth survives and thrives after a catastrophe. It proves that the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction was the primary catalyst for the rise of jawed vertebrates. Without the “icehouse” shift and the subsequent drowning of the shallow seas, the ancestors of modern sharks, bony fish, and eventually humans might have remained marginal, obscure creatures.

By integrating biogeography, morphology, and the fossil record, scientists can now see the long-term patterns that govern life. This study explains why our modern marine ecosystems are built on the descendants of these specific survivors rather than the alien-looking conodonts or trilobites of the ancient past. It reminds us that mass extinctions do more than just destroy; they act as a biological reset that can propel a few lucky survivors from the edges of existence to the center of the world’s stage.

Study Details

Wahei Hagiwara et al, Mass Extinction Triggered the Early Radiations of Jawed Vertebrates and Their Jawless Relatives (Gnathostomes), Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aeb2297. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aeb2297