In the silent, dark expanse of the early universe, something massive was stirring. Long before the stars and galaxies we see today had fully matured, a group of young researchers at the Cosmic Dawn Center, part of the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen, peered into the deep past to witness the birth of a giant. What they found was a cosmic titan that shouldn’t have existed—at least, not in the way our current maps of the universe suggested. By pointing their instruments toward the furthest reaches of space and time, they uncovered a story of growth and survival that challenges our fundamental understanding of how the largest structures in the cosmos were built.

A Ghostly Reservoir in the Deep Past

The story began with a mystery hidden within an extremely large galaxy cluster caught in the earliest stages of its evolution. As the researchers looked back into the infancy of the cosmos, they expected to find a system beginning to settle into a predictable pattern. Instead, they were met with an overwhelming presence of cold, neutral hydrogen gas. This was no small pocket of matter; it was a dense, sprawling reservoir that was much greater than any existing scientific model had predicted.

This gas is the raw fuel of the universe, the primordial building block that collapses under its own weight to ignite the fires of star formation. To find such a high density of this material still active and “feeding” the growth of galaxies within a cluster was a shock. This structure was already massive, containing an enormous amount of material, but the presence of so much neutral gas suggested it was still in the middle of a frantic growth spurt. According to Kasper Heintz, an Assistant Professor and the study’s lead author, this was a sight never before seen in these systems so far back in the universe’s history. If this cluster were allowed to continue its development to the present day, it would likely evolve into one of the largest galaxy clusters ever witnessed.

Defying the Light of the First Stars

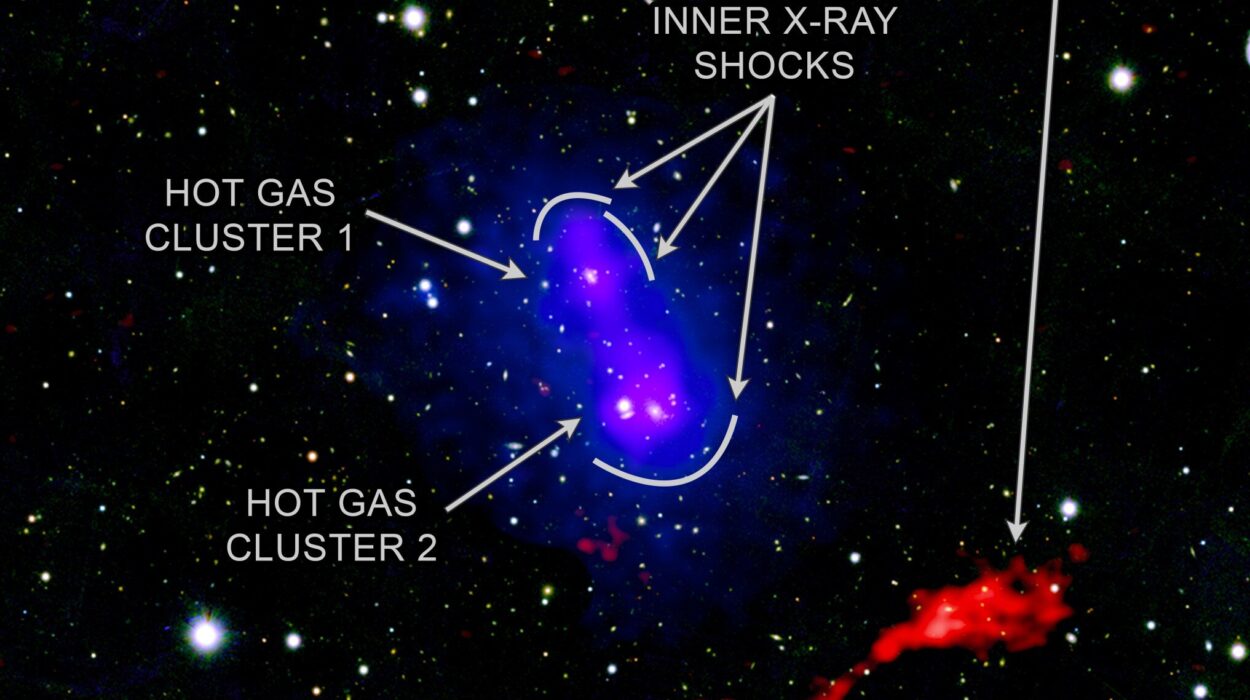

The discovery did more than just present a large structure; it created a paradox. To understand why this gas was so surprising, one must look at the timeline of the universe itself. About one billion years after the Big Bang, the universe was supposed to be undergoing a dramatic transformation known as large-scale ionization. The prevailing theory was that as the first luminous galaxy clusters flickered to life, they would radiate intense light and energy. This radiation was thought to be so powerful that it would strip electrons from the surrounding primordial matter, turning neutral gas into an ionized state.

Scientists believed that these “pockets” of brilliant light were the driving force behind the last major phase transition in cosmic history, effectively clearing the “fog” of the early universe. However, the Copenhagen team’s observations tell a different story. The massive amounts of non-ionized gas they found contradicted the assumption that the radiation from these early clusters was enough to transform the environment so quickly. There is a much larger proportion of cold, neutral hydrogen gas remaining in these structures than anyone thought possible. It appears the universe’s “nursery” was much more resilient to the heat of the first stars than our models ever accounted for.

A New Vision Through the Golden Eye

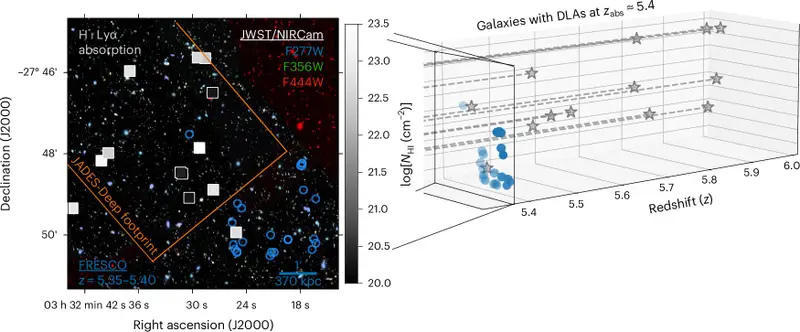

The breakthrough required more than just looking; it required a new way of seeing. Chamilla Terp, a student whose work began during her bachelor’s project and continued into her master’s thesis, became a central figure in this detective story. Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), she began investigating several different types of galaxy clusters to see if the first discovery was an outlier or part of a broader pattern.

One of the greatest challenges in observing the deep universe is the “clutter” of space. When a telescope looks at a distant galaxy, it must peer through vast distances filled with other gas and matter. Terp succeeded in developing a groundbreaking method that allowed the team to separate the hydrogen gas belonging to the specific galaxies they were studying from the gas lying “in front” of them along the line of sight. By filtering out the background noise of the enormous space between the telescope and its target, the researchers achieved a level of precision that was previously impossible. This methodological leap allowed them to track the evolution of individual galaxy clusters with startling clarity, revealing that these overdensities of cold gas were appearing more frequently than anyone expected.

The Mystery of the Missing Giants

As the James Webb Space Telescope continues to look deep into a small field of view, it is effectively acting as a time machine. By looking deep, it looks far back, capturing the universe in its most formative moments. The data is now raising a haunting new question for the team at the Cosmic Dawn Center. If these massive, gas-rich structures were so numerous in the early universe, where are their descendants today?

The researchers are finding the early births of numerous very large structures, yet when we look at the local universe—the space closer to us in time—these specific types of giants seem to be missing. They appear to have disappeared or transformed in ways that the current developmental history of the universe cannot yet explain. The search has now shifted from simply finding these structures to understanding their fate. Why did they vanish along the way, and what does their disappearance tell us about the ultimate destiny of the cosmos?

Why This Cosmic Portrait Matters

This research is fundamental because it forces a rewrite of the biography of our universe. By proving that cold, neutral hydrogen gas persisted in massive amounts long after it was supposed to have been ionized, the study challenges the existing timeline of how the universe transitioned from a dark, neutral void into the bright, transparent expanse we see today. It suggests that the large-scale ionization process was more complex and perhaps slower than previously imagined.

Furthermore, the discovery of these “missing” large structures suggests there are significant gaps in our understanding of how the universe evolves over billions of years. Understanding the relationship between primordial matter and the birth of galaxy clusters is essential for explaining how the largest objects in existence came to be. This work doesn’t just look at distant lights; it investigates the very plumbing of the cosmos, showing us that the history of the universe is far more mysterious, and far more crowded with giants, than we ever dared to dream.

Study Details

Kasper E. Heintz et al, A dense web of neutral gas in a galaxy proto-cluster post-reionization, Nature Astronomy (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02745-x