For as long as humans have looked at the night sky, we have wondered about the invisible forces that shape the worlds circling other suns. We can see the light of distant stars, but their more secretive influences—the solar winds, magnetic storms, and particles—have long remained hidden from our view. These elements, collectively known as space weather, are the silent architects of a planet’s fate. In our own solar system, we know that these particles can be even more influential than light when it comes to determining what happens to a planet. Yet, across the vast reaches of the galaxy, studying this invisible weather has been an exercise in frustration. Astronomers cannot simply fly a probe to a distant star and park a monitoring device in its orbit.

However, nature may have already done the hard work for us. Luke Bouma of Carnegie has discovered that a specific type of star might be carrying its own monitoring equipment. By looking at a group of celestial “oddballs,” Bouma and his collaborator, Moira Jardine of the University of St. Andrews, have realized that certain stars are surrounded by naturally occurring space weather stations. These stations are not made of metal and circuits, but of plasma, trapped in a magnetic dance that reveals the hidden environment of the star’s immediate surroundings.

The Mystery of the Shifting Shadows

The journey to this discovery began with a puzzle involving a class of stars known as M dwarfs. These stars are the most common in our galaxy, characterized by being smaller, cooler, and dimmer than our own sun. While they are small, they are incredibly influential; most M dwarfs are known to host at least one Earth-sized rocky planet. But for a long time, a specific subset of these stars, called complex periodic variables, kept astronomers guessing. These are young, rapidly rotating stars that exhibit strange, recurring dips in their brightness.

To an observer on Earth, these “oddball little blips of dimming” were a source of confusion. Scientists weren’t sure if they were looking at starspots—dark patches on the star’s surface—or if there was some kind of physical material orbiting the star and blocking its light. These blips were inconsistent and mysterious, appearing as rhythmic but complex shadows that defied easy explanation. They were the “weird little mysteries” of the stellar neighborhood, until Bouma and Jardine decided to take a closer look at what was happening right above the stellar surface.

A Doughnut Made of Plasma

To solve the mystery, the researchers created what they call spectroscopic movies of a complex periodic variable. This technique allowed them to visualize the movement of material around the star in a way that traditional snapshots could not. What they found was not a solid object or a simple blemish on the star’s face. Instead, they discovered large clumps of cool plasma.

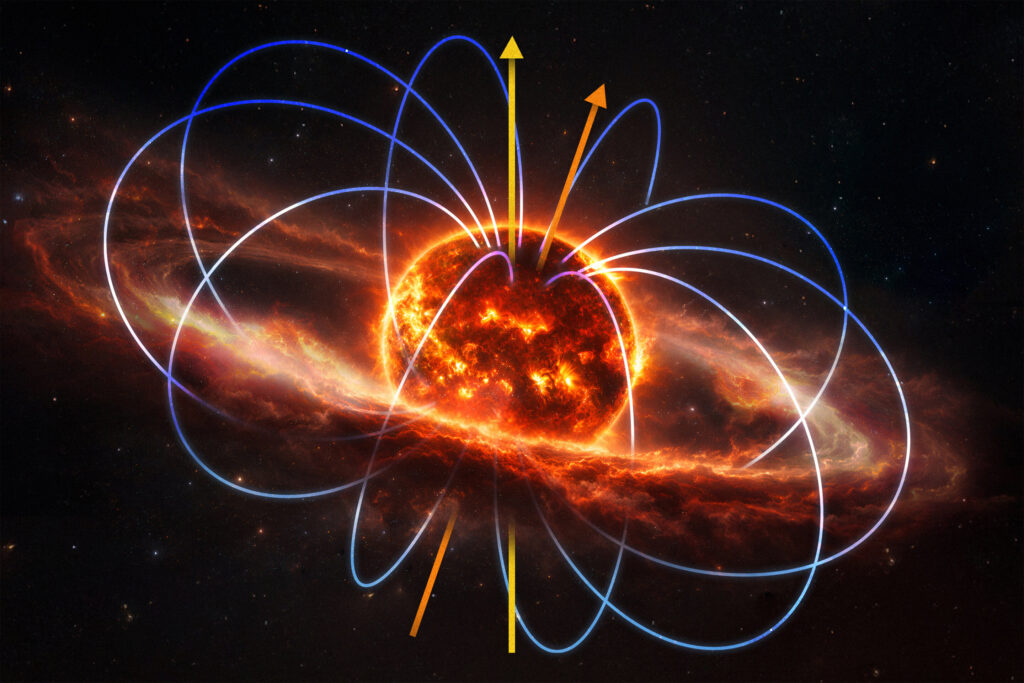

This plasma isn’t just floating away into space. It is caught in the star’s magnetosphere, the powerful magnetic environment that surrounds the stellar body. Because the star is spinning so quickly, its magnetic field acts like an invisible tether, dragging these massive clumps of plasma around with it. Together, these clumps form a doughnut shape known as a torus. As this “doughnut” of charged particles revolves around the star, it passes between the star and our telescopes, creating the strange dips in brightness that had puzzled astronomers for years.

Turning a Mystery Into a Monitor

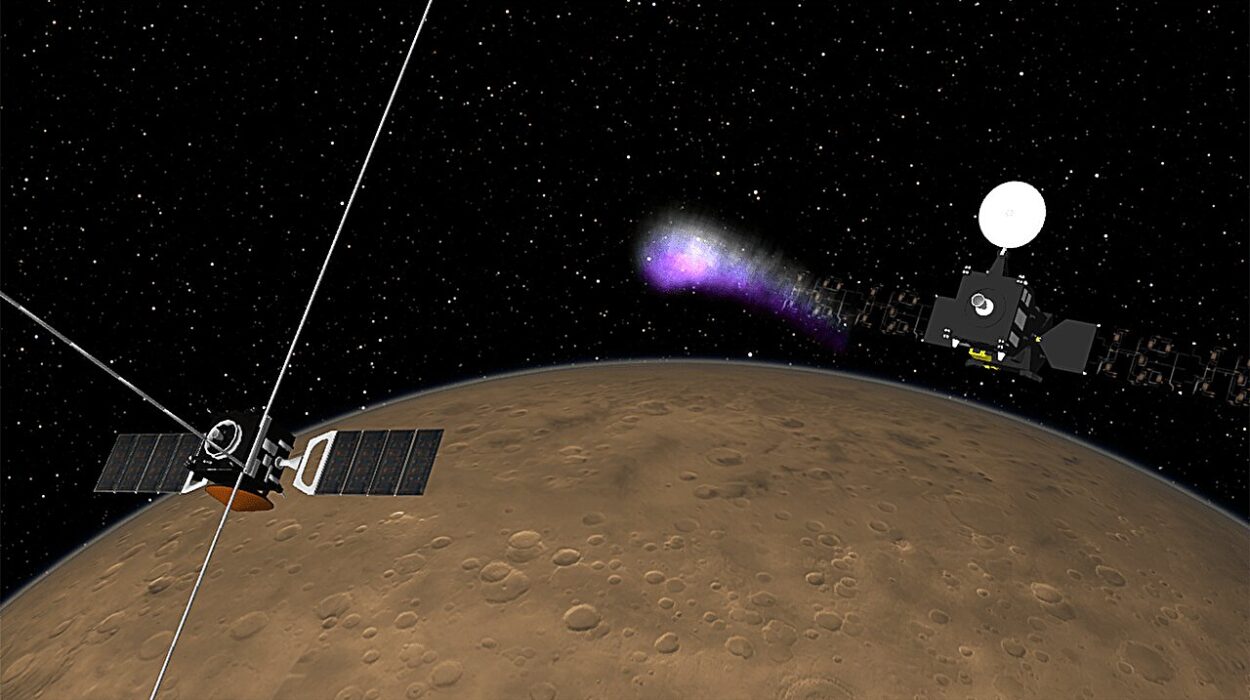

Once the team understood that they were looking at a plasma torus, the discovery shifted from a mere curiosity into a powerful scientific tool. These toruses effectively serve as space weather stations. Because the plasma is physically influenced by the star’s energy and magnetism, observing how the plasma moves and where it concentrates tells scientists exactly what is happening in the star’s immediate vicinity.

It provides a window into the space weather of a distant system. By watching the plasma, researchers can determine how strongly the material is influenced by the magnetic field and how the star’s internal engine is pushing and pulling on its surroundings. It is a serendipitous breakthrough; a phenomenon that was once an annoying inconsistency in data has become a primary source of information. Bouma and Jardine estimate that at least 10% of M dwarf stars possess these plasma features during the early stages of their lives. This means there are potentially millions of these natural “stations” scattered throughout the galaxy, waiting to be read.

Why This Cosmic Weather Report Matters

Understanding the environment around M dwarfs is critical because these stars are the most likely hosts for the planets we hope to one day call “Earth-like.” While many of these Earth-sized rocky planets are currently viewed as inhospitable—often being too hot for liquid water or lacking atmospheres—they serve as vital laboratories. By studying them, we learn how a star shapes the very ground its planets are made of.

The presence of intense radiation and frequent stellar flares can strip a planet of its potential for life, but we cannot fully understand that process without measuring the particles and magnetic storms that cause it. This research provides the missing link. While we have always been able to observe the light of a star, we have struggled to see the space weather that might be the true deciding factor in habitability.

The discovery of the plasma torus gives astronomers a new way to probe the relationship between a star and its planets. It helps answer whether a world can hold onto an atmosphere or if it will be scorched into a barren rock by its parent star. As we look toward the future, these “oddball” stars will be the keys to understanding the planet-star relationships that define our universe. Even if we do not yet know if any of these distant worlds are truly hospitable, we now have the tools to watch the weather and find out.

More information: Luke G. Bouma et al, A Plasma Torus around a Young Low-mass Star, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ade39a