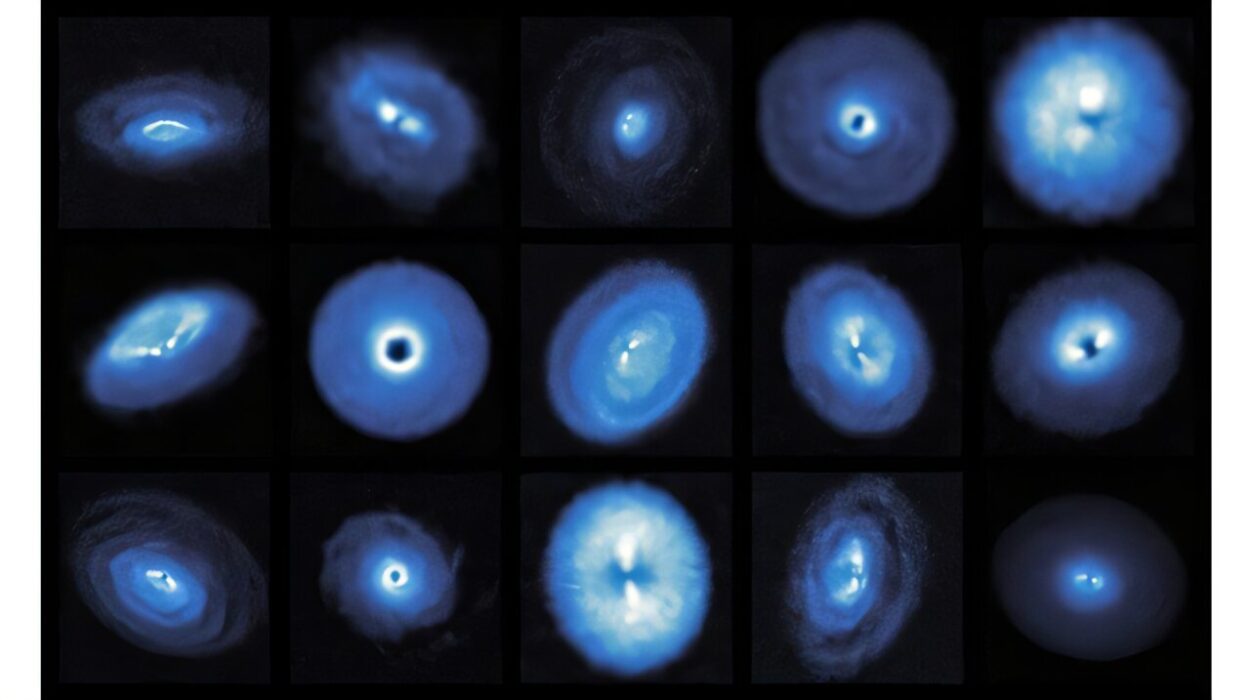

There are moments in scientific discovery that feel as though we’ve crossed a threshold—moments when what was once hidden in the shadows suddenly comes into sharp focus. For astronomers studying the Apep system, the arrival of the James Webb Space Telescope’s image was one of those revelatory moments. It was like walking into a dark room and switching on a light—everything came into view.

Before Webb, the Apep system was shrouded in mystery. It was known to host two aging Wolf-Rayet stars, celestial giants shedding vast clouds of dust. But only a single shell of this dust had ever been observed. The existence of multiple shells—repeating layers of dust emitted over centuries—was merely a hypothesis. Astronomers searched for them using ground-based telescopes, but found nothing. That is, until Webb turned its powerful gaze on Apep, revealing not one, but four spiraling clouds of dust, stretching outward in a perfectly organized pattern.

The Mystery of the Expanding Shells

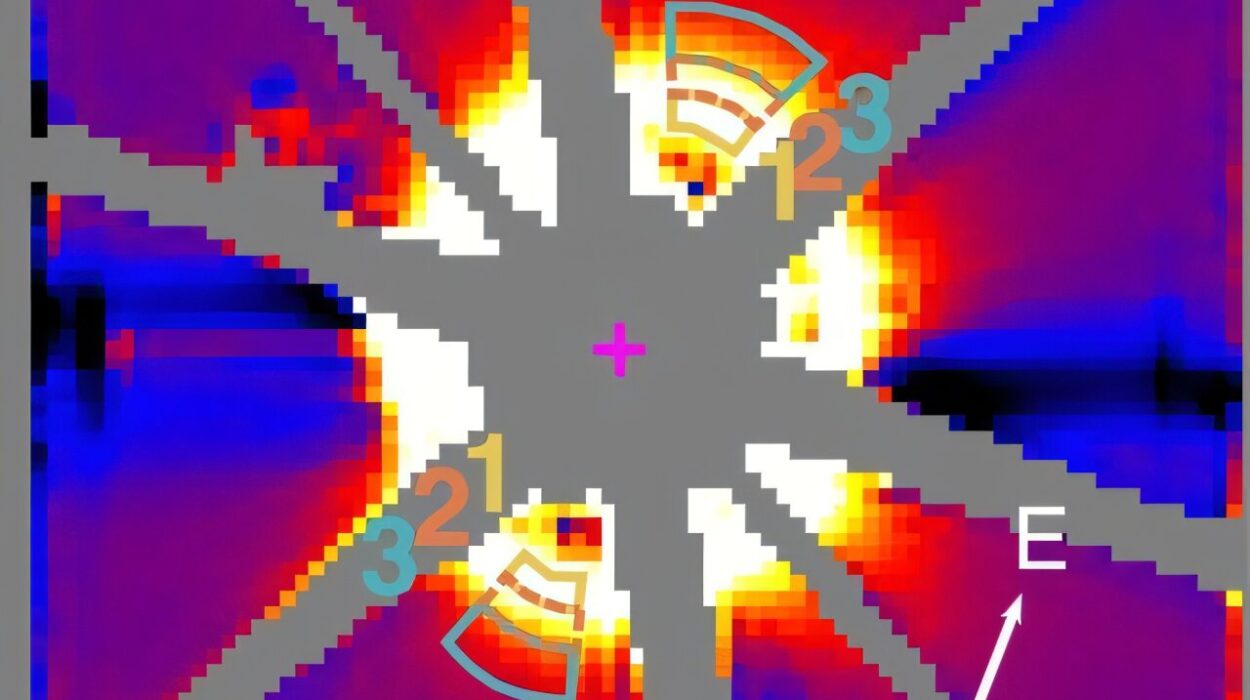

The stunning image that emerged from Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) showed an intricate dance of dust, spiraling outward in four distinct shells, expanding in a remarkably precise pattern. Each shell was a clue to the gravitational ballet playing out in this star system. The outermost shell, faint and almost transparent at the edges of the image, hinted at something more profound—something that had remained hidden from all previous observations.

“It’s as if the stars in the Apep system were carefully crafting these shells over time,” said Yinuo Han, lead author of the paper that described the findings. The rings were ejected in perfect synchrony over the past 700 years by the two Wolf-Rayet stars—massive, aging stars that expel material as they approach the end of their lives. These shells are not random; they follow a predictable, repetitive pattern that speaks to the precise rhythms of this distant cosmic dance.

What was even more remarkable was the way Webb’s images, combined with years of data from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), helped astronomers pin down the stars’ orbit. The two Wolf-Rayet stars in Apep complete an orbit every 190 years. They pass close to one another every 25 years, sending out massive, carbon-rich dust clouds as they collide. This slow, rhythmic creation of dust sets Apep apart from other Wolf-Rayet systems, where dust tends to be ejected over much shorter timescales—sometimes only a few months.

The Enigmatic Role of a Third Star

But Apep’s story doesn’t end with the two Wolf-Rayet stars. There is a third, massive supergiant star in the system—one that has a profound influence on the shape and behavior of the dust clouds. As the two Wolf-Rayet stars send out their dust, the supergiant’s powerful gravitational pull carves holes through each shell, creating distinct cavities that give the dust its unique structure.

Ryan White, a Ph.D. student at Macquarie University, vividly described the effect: “The central point of light in Webb’s image shows a cavity in the dust, more or less in the same position in each shell, forming a V shape like a funnel.” The influence of this third star was a key element of the discovery, and Webb’s observations were the “smoking gun” that confirmed its gravitational connection to the other stars. Prior to Webb’s observations, scientists had suspected the existence of this third star, but the precise mechanics of how it interacted with the dust clouds had remained unclear.

The realization that this third star was not just a bystander, but an active participant in shaping the dust, was a major breakthrough. White reflected on this moment of discovery: “I was shocked when I saw the updated calculations play out in our simulations.” Webb had not just captured images—it had solved a longstanding mystery, offering up concrete evidence of how the third star was carving out cavities in the dust as it orbited the other two stars.

The Dance of the Wolf-Rayet Stars

The behavior of the two Wolf-Rayet stars in Apep is dramatic. These stars are not idle. Their strong stellar winds collide and mix as they orbit one another, creating violent bursts of dust at speeds ranging from 1,200 to 2,000 miles per second. In most similar systems, this dust is ejected over just a few months, making Apep’s long-lasting, cyclical dust clouds all the more unusual. The intense heat of the dust, made mostly of amorphous carbon, is another reason Webb’s infrared instruments could detect the shells with such precision. These carbon dust grains retain heat even as they drift farther from their parent stars.

The beauty of the dust—dense, warm, and stretching across vast distances—was only made visible because of Webb’s unprecedented ability to observe in the infrared. Without this capability, the light emitted by the dust would be far too faint to detect from Earth’s surface.

Why This Matters

The discovery of Apep’s spiraling dust clouds and the confirmation of its three-star system have profound implications for our understanding of stellar evolution. Wolf-Rayet stars, like those in Apep, are some of the most massive and enigmatic stars in the universe. They are in the final stages of their lives, having shed much of their mass, and are destined to explode as supernovae. This event will send their material into space, potentially triggering a gamma-ray burst—a rare and intense event that could provide even more insights into the extreme conditions at the ends of stellar life cycles.

There are fewer than a thousand Wolf-Rayet stars in our Milky Way galaxy, and Apep is one of the rarest examples—two Wolf-Rayet stars in a single system, bound together in a slow, centuries-long orbit. Most Wolf-Rayet binaries only contain one of these stars. Apep, with its dust-creating rhythm and dynamic three-star system, offers astronomers a unique laboratory for studying the life cycles of massive stars.

As astronomers continue to study Apep, they hope to answer lingering questions—particularly about the precise distance of the system from Earth. But more than that, the findings mark a milestone in our understanding of the universe’s most powerful and mysterious stars. This research not only illuminates the intricate workings of Apep, but it also helps us understand the broader processes that govern stellar death, dust formation, and the birth of new cosmic structures.

Apep’s story is just beginning to unfold, and with each new observation, we are drawn deeper into the mysteries of the cosmos. Through the lens of the James Webb Space Telescope, we are witnessing not just the final moments of distant stars, but the eternal dance of creation and destruction that shapes our universe.

More information: Yinuo Han et al, The Formation and Evolution of Dust in the Colliding-wind Binary Apep Revealed by JWST, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae12e5

Ryan M. T. White et al, The Serpent Eating Its Own Tail: Dust Destruction in the Apep Colliding Wind Nebula, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/adfbe1