In the autumn of 1604, the German astronomer Johannes Kepler looked up at the night sky and witnessed a “new star” burning with such intensity that it outshone the planets and remained visible for weeks. While Kepler could only marvel at the brilliance of the light, he was actually witnessing the violent death of a star located 17,000 light-years from Earth. For centuries, that explosion remained a static memory in history books, a sudden flash followed by a slow fade into darkness. However, thanks to more than two and a half decades of modern technology, we are no longer just looking at a ghost of the past. We are watching it move, grow, and breathe.

A Stellar Ghost Comes to Life

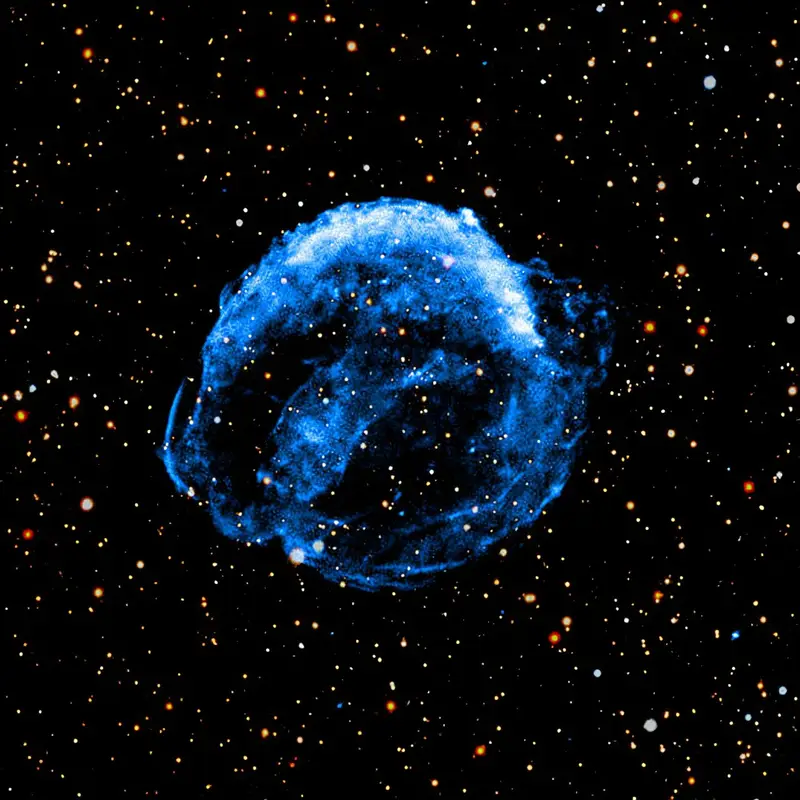

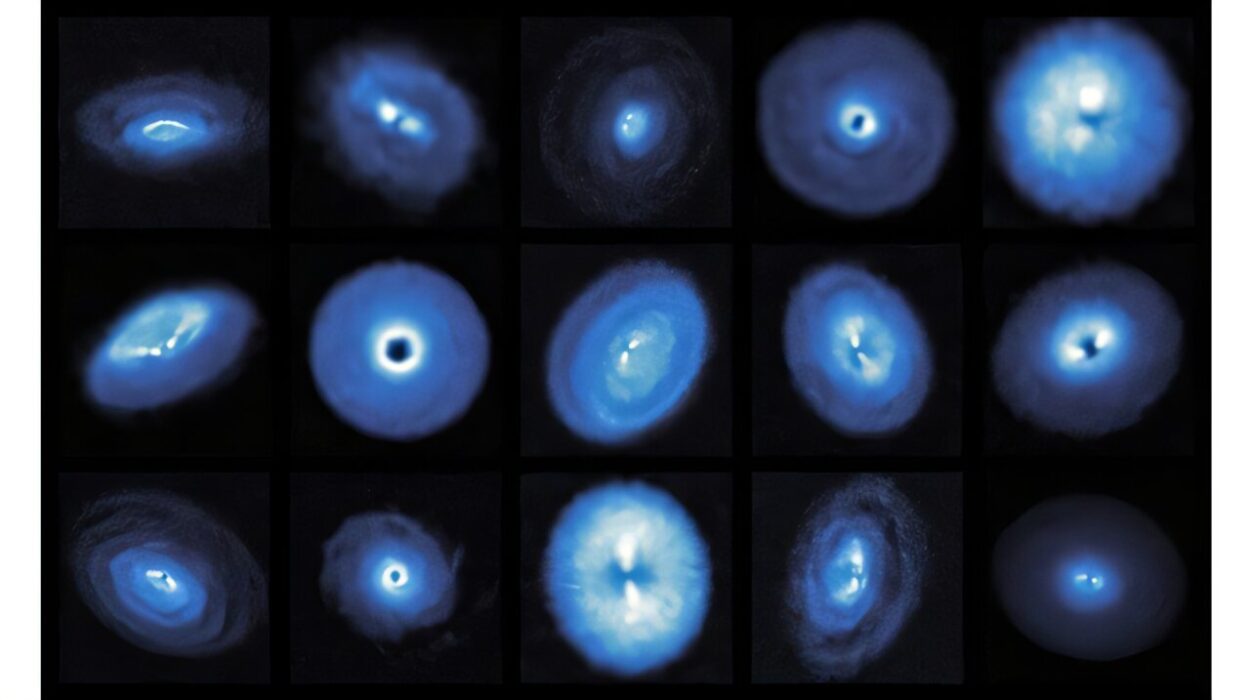

For twenty-five years, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory has kept its sharp gaze fixed on the debris field left behind by that ancient blast, known today as Kepler’s Supernova Remnant. Because the explosion heated the surrounding material to millions of degrees, the remnant glows with incredible intensity in X-ray light, a spectrum invisible to the human eye but clear as day to Chandra. By stitching together data captured in 2000, 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2025, researchers have created the longest-spanning video of a supernova remnant ever released.

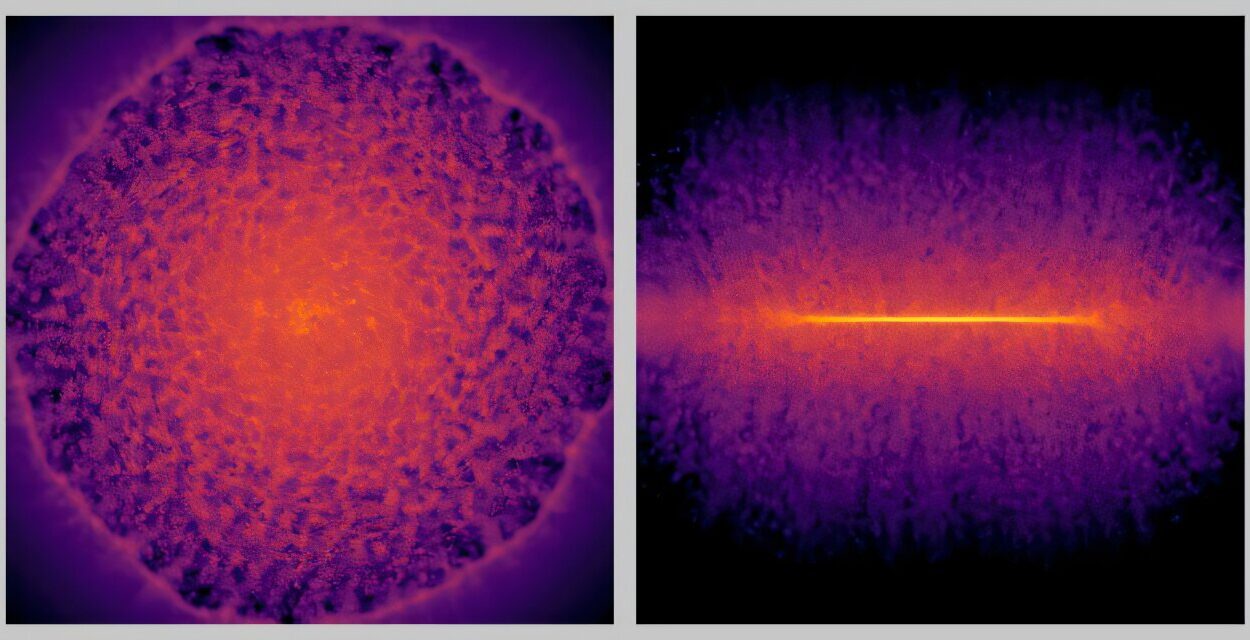

This cosmic time-lapse reveals a story that began with a white dwarf star. This small, dense stellar corpse reached a critical mass—either by siphoning gas away from a nearby companion star or by colliding with another white dwarf—and triggered a Type Ia supernova. These specific types of explosions are the gold standard for astronomers; because they explode with predictable brightness, they are used as cosmic yardsticks to measure the expansion of the universe. Through the eyes of Chandra, the “shattered star” is no longer a still photograph, but a dynamic, expanding cloud of debris that continues to push outward into the void.

The Friction of the Deep Void

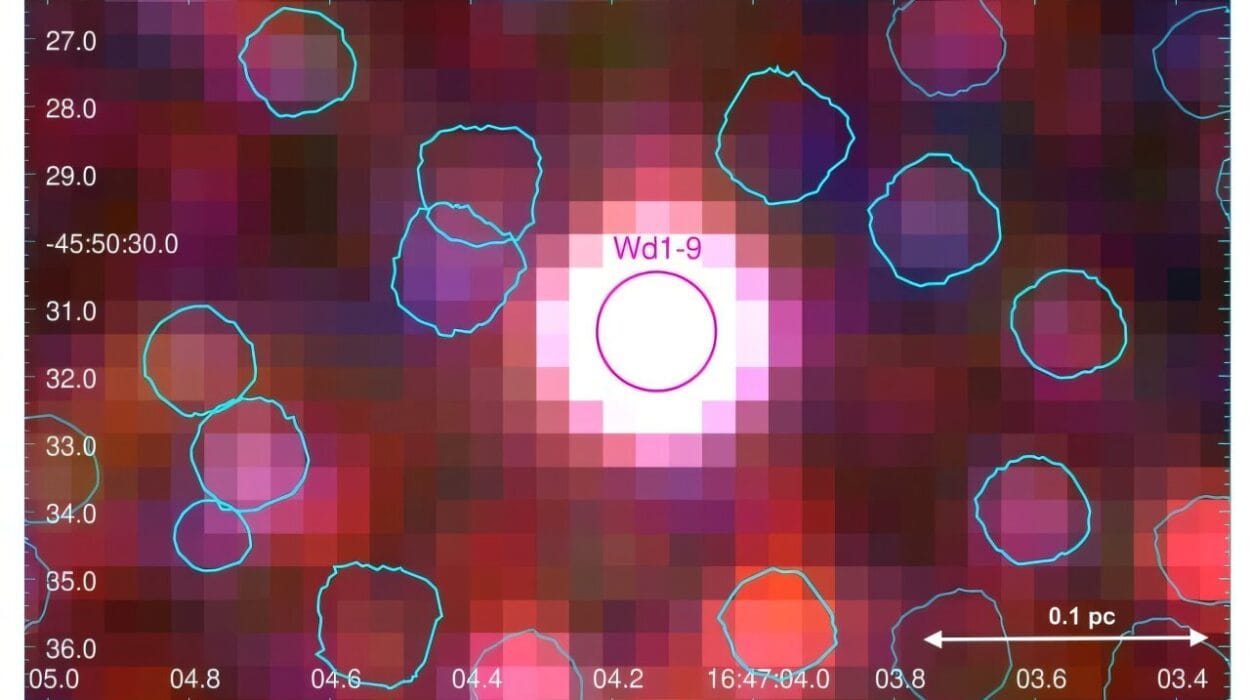

As the debris from the Type Ia explosion screams outward, it does not move through empty space. Instead, it acts like a snowplow, slamming into gas and dust that the star had already cast off before its final moments. This interaction creates a blast wave, the leading edge of the explosion that serves as the first point of contact between the dying star and the galaxy. By observing this wave over a quarter of a century, scientists have noticed something peculiar: the explosion is not expanding evenly in all directions.

The video shows a dramatic “tug-of-war” in speeds. Toward the bottom of the field of view, the debris is racing away at a staggering 13.8 million miles per hour, which is roughly 2% of the speed of light. In contrast, the material moving toward the top of the image is significantly more sluggish, traveling at “only” 4 million miles per hour, or 0.5% of the speed of light. This discrepancy isn’t a fluke of the explosion itself, but a map of the environment. The gas at the top is much denser than the gas at the bottom, creating a cosmic barrier that slows the remnant down, while the bottom section finds a path of less resistance and hurtles forward.

Measuring the Rim of a Cataclysm

To understand the mechanics of this ancient catastrophe, researchers turned their attention to the rims of the remnant. These thin, glowing edges mark the boundary of the blast wave. By meticulously measuring the widths of these rims and comparing them to the speed at which they travel, astronomers can work backward to solve a cosmic puzzle. This data allows them to determine the exact conditions of the star’s surroundings and the specific physics of the explosion that Johannes Kepler saw four centuries ago.

Every pixel of the Chandra data represents a piece of a “shattered star” crashing into the unknown. The ability to track these changes over twenty-five years is a testament to the longevity and precision of the observatory. Only a tool with such sharp X-ray vision could detect these subtle shifts in the debris field, allowing humans to watch a process that usually unfolds over timescales far beyond a single human life. The plot of this story is just beginning to unfold, as each year of data adds a new chapter to the biography of a star that died long before the invention of the telescope.

Why the Death of a Star Matters

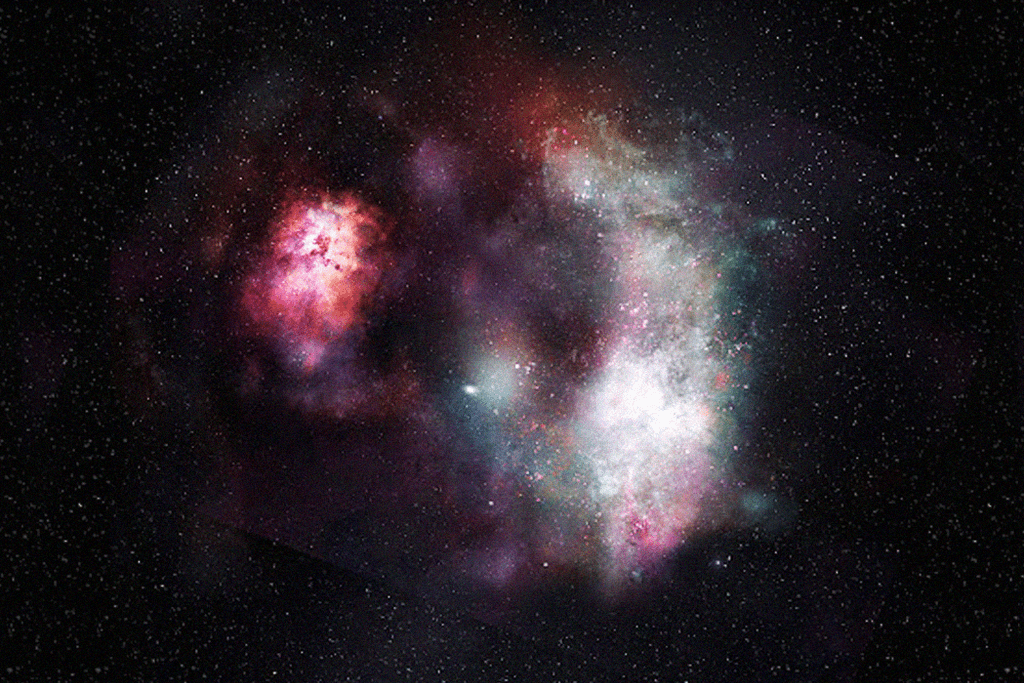

This research is about far more than just tracking a distant cloud of gas; it is an investigation into the very chemistry of our existence. Supernova explosions are the primary engines of the universe, responsible for forging and distributing the elements that eventually form the building blocks of new generations of stars and planets. The iron in our blood and the calcium in our bones were once part of a stellar interior, hurled into space by a blast wave just like the one seen in Kepler’s remnant.

By studying how these remnants behave and how they interact with their surroundings, we gain a clearer picture of our own cosmic history. Understanding the speeds, temperatures, and densities of these debris fields helps scientists predict how the galaxy recycles itself. Every time a white dwarf explodes, it seeds the universe with the “lifeblood” required to create new worlds, making the violent end of Kepler’s star a fundamental part of the story of how we came to be.