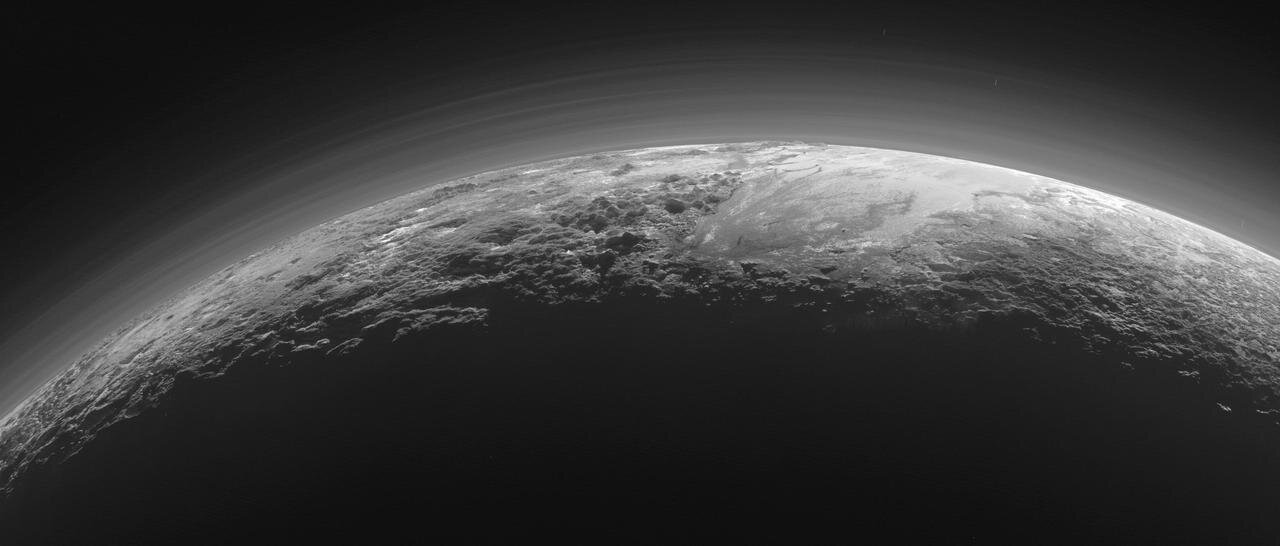

For billions of years, the Moon has served as a silent witness to the chaotic history of our solar system. While Earth’s restless surface—churned by tectonic plates, rushing water, and the breath of life itself—erased the footprints of its own creation long ago, the lunar landscape remained a frozen archive. In the deep, permanently shadowed regions of the lunar poles, temperatures are so low that time effectively stands still. Here, scientists believe, lies a pristine record of the prebiotic organic molecules delivered by ancient comets and asteroids. These molecules are the raw ingredients of existence, the precursors to DNA that might reveal how inert matter first stirred into biological life.

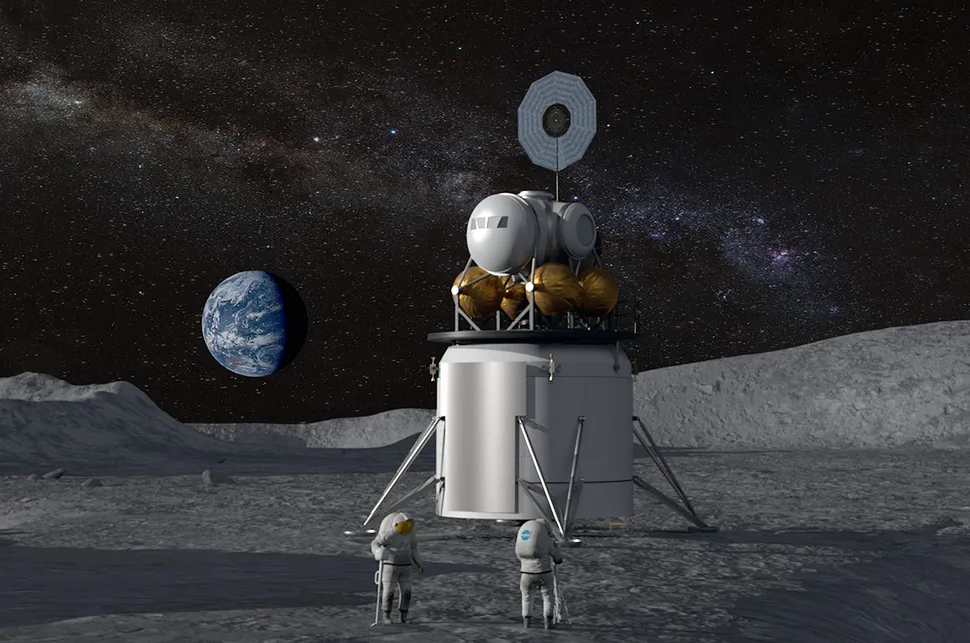

However, as humanity prepares for a new era of lunar exploration, a paradoxical shadow looms over this “natural laboratory.” The very machines designed to uncover the secrets of our origins may inadvertently destroy the evidence before we can even reach it. According to a new study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, the exhaust from lunar landers could trigger a rapid and nearly unstoppable wave of contamination, spreading organic pollutants across the entire celestial body in a matter of days.

A Ghostly Migration Across the Lunar Silence

The study, led by Francisca Paiva and senior author Silvio Sinibaldi, utilized complex computer simulations to track the invisible aftermath of a spacecraft touchdown. Using the European Space Agency’s Argonaut mission as a case study, the researchers focused on methane, the primary organic compound released when certain spacecraft propellants burn. What they discovered was a molecular “mad dash” that defied expectations of how pollutants behave in a vacuum.

On Earth, an exhaust plume is hemmed in by a thick atmosphere, but the Moon offers no such resistance. With almost no air molecules to collide with, the methane molecules are governed almost entirely by gravity and the energy of the sun. The researchers described these trajectories as ballistic, meaning the molecules do not drift like smoke; instead, they bound across the landscape like tiny, energetic bouncy balls. In this empty room of a world, a molecule can “hop” thousands of miles without hitting a single obstacle.

The speed of this migration was the most startling revelation. The model demonstrated that even if a spacecraft lands at the South Pole, its exhaust can reach the North Pole in less than two lunar days. Within a mere seven lunar days—roughly seven months in Earth time—over half of the total exhaust methane has successfully navigated its way to the poles, finding a permanent home in the darkness.

The Cold Traps of the Frozen Poles

The Moon’s poles are home to “cold traps,” where the lack of sunlight creates a thermal vacuum. As the methane molecules hop across the surface, they are energized by UV radiation and the solar wind, but once they tumble into the frigid depths of a permanently shadowed region, their movement slows to a crawl. They become stuck, mingling with the ancient ice that has sat undisturbed for eons.

The simulations revealed a lopsided but devastating distribution of this pollution. About 42% of the exhaust methane ended up trapped at the South Pole landing site, while 12% migrated all the way to the North Pole. This means that regardless of where a mission touches down, the contamination is effectively global. The research suggests there are no “safe” or “foolproof” landing sites if the goal is to keep the lunar poles in a pristine, pre-human state.

This creates a high-stakes conflict for the European Space Agency and other global entities. To study the prebiotic organic molecules that might fill the gap in our understanding of how chemistry becomes biology, we must land on the Moon. Yet, the moment we arrive, we risk “masking” those ancient signals with modern, man-made noise. If a scientist finds methane or other organic signatures in a lunar crater, they may struggle to prove whether it was delivered by a comet four billion years ago or by a rocket engine four months ago.

Safeguarding the Archives of the Solar System

The researchers are now calling for a fundamental shift in how we approach lunar missions, treating the Moon with the same ecological respect we afford to Antarctica or our most precious national parks. The goal is not to stop exploration, but to integrate planetary protection strategies into the very design of the missions. This could involve choosing colder landing sites that might better corral exhaust molecules or developing new instruments to measure and validate these contamination models in real-time.

Sinibaldi and Paiva are also looking beyond methane. Future research may examine how other materials—such as the paint, rubber, or hardware components of the spacecraft—might shed particles and further complicate the lunar environment. There is also a slim hope that the exhaust molecules might only settle on the topmost layer of the ice, potentially leaving the deeper, more ancient materials unscathed for future researchers to find.

Ultimately, this research matters because it highlights a fleeting window of opportunity. The Moon is a unique scientific investment, a rare “clean room” where the history of the solar system is preserved in high resolution. As private companies and governments race toward the lunar surface, the window to study a pristine world is rapidly closing. By understanding the invisible, hopping path of a single methane molecule, scientists hope to ensure that our quest to find the origins of life doesn’t accidentally erase the very answers we are looking for.

More information: Francisca S. Paiva et al, Can Spacecraft‐Borne Contamination Compromise Our Understanding of Lunar Ice Chemistry?, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2025je009132