Cell division—known scientifically as mitosis—is one of life’s most crucial events. Every time a cell divides, it must perfectly copy its DNA and distribute it between two daughter cells. This extraordinary process happens billions of times each day in the human body, maintaining tissues, fueling growth, and repairing damage.

For decades, scientists believed that as cells divide, their genetic material—the genome—undergoes a kind of temporary “shutdown.” In this view, the 3D architecture of the genome, normally responsible for regulating which genes are active, collapses entirely during division. The cell, they thought, wipes its structural slate clean before rebuilding it once division is done.

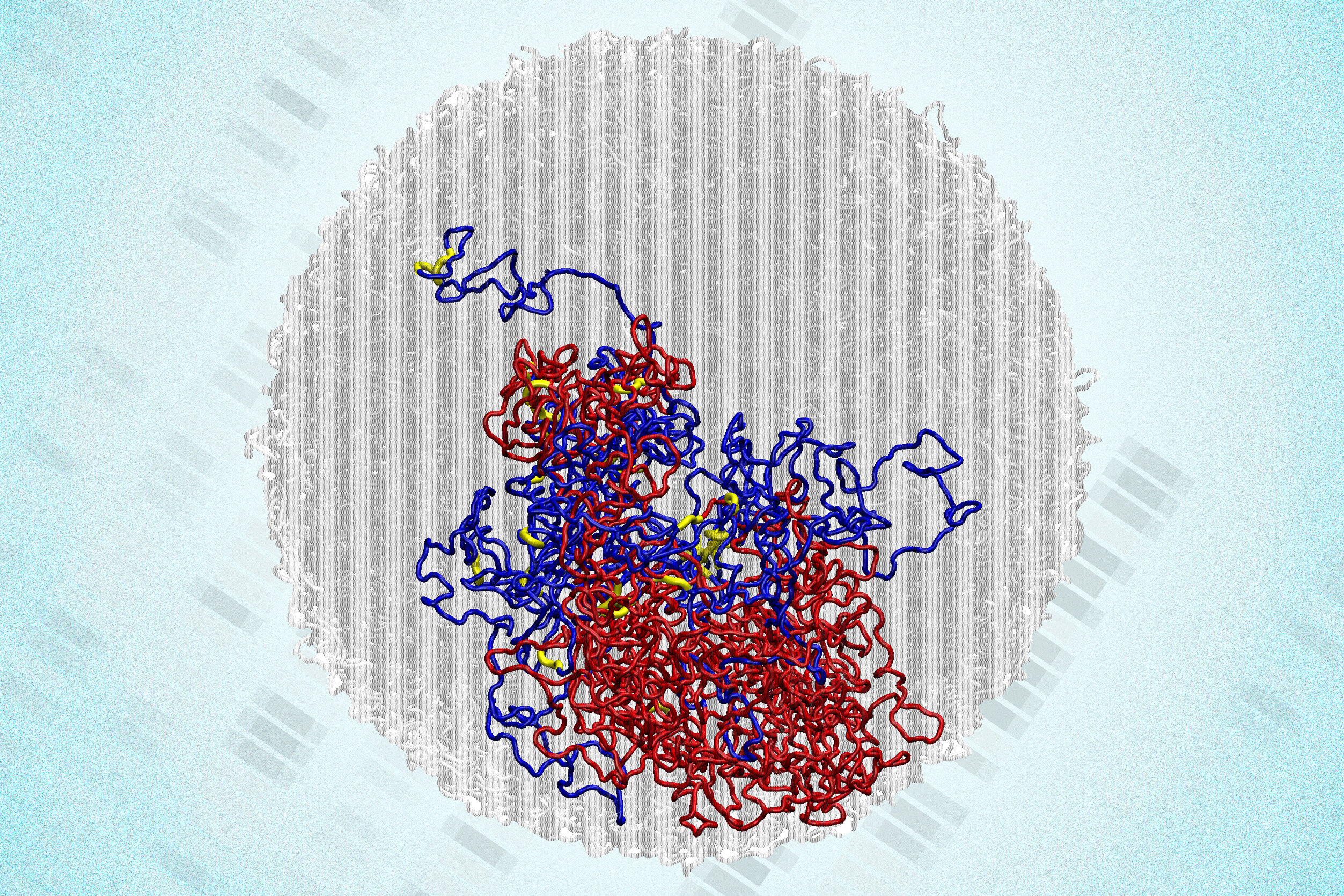

But a groundbreaking new study from researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has upended that idea. The findings, published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, reveal that the genome does not lose all its structure during mitosis. In fact, tiny three-dimensional loops within the genome—connections that help regulate gene activity—remain intact and even become stronger as the chromosomes compact.

This discovery fundamentally reshapes our understanding of how cells preserve genetic “memory” from one generation to the next.

Beyond the Blank Slate

“This study really helps to clarify how we should think about mitosis,” says Anders Sejr Hansen, associate professor of biological engineering at MIT and one of the study’s senior authors. “In the past, mitosis was thought of as a blank slate, with no transcription and no structure related to gene activity. And we now know that that’s not quite the case. What we see is that there’s always structure. It never goes away.”

That statement overturns decades of biological assumption. Previously, scientists imagined that when chromosomes condense for division, the fine details of the genome’s 3D organization—loops, compartments, and domains—disappear completely. The new study shows that this erasure never fully happens. Instead, certain small-scale structures persist through the process, potentially helping cells retain information about which genes were active before division.

These findings not only challenge a long-held belief about cell division but also reveal a new layer of biological continuity, one that connects the past and future of every cell.

A New Window into the Genome

The breakthrough was made possible by a powerful new mapping technology known as Region-Capture Micro-C (RC-MC), a method developed by Hansen’s lab.

Traditional tools for studying genome structure, such as the Hi-C technique, were revolutionary in revealing that DNA folds into intricate loops inside the nucleus. However, they lacked the resolution to capture small, specific interactions—particularly those between genes and their regulatory elements, like enhancers.

RC-MC changes that. By cutting the genome into smaller fragments and focusing on particular regions, the technique can visualize genome structures with 100 to 1,000 times more detail than before. It’s like switching from a blurry black-and-white image to a high-definition color portrait.

With this tool, the MIT team discovered previously unseen structures they call “microcompartments.” These are tiny clusters of loops formed when enhancers and promoters—regions of DNA that control gene activation—stick together.

Initially, scientists thought these microcompartments would vanish during mitosis, just like larger structures known as A/B compartments and topologically associating domains (TADs). But to their surprise, the researchers found the opposite.

The Surprise Inside Mitosis

As chromosomes condensed and prepared for division, the team observed that microcompartments didn’t fade away. They became more prominent.

“We went into this study thinking, well, the one thing we know for sure is that there’s no regulatory structure in mitosis,” Hansen recalls. “And then we accidentally found structure in mitosis.”

This revelation was startling. The persistence of microcompartments suggests that even as the genome compacts, it retains a subtle memory of its regulatory interactions. The physical closeness caused by chromosomal tightening seems to strengthen these tiny loops, perhaps setting the stage for the cell to quickly reactivate the right genes once division ends.

The discovery was confirmed by the fact that while large genome structures like TADs and A/B compartments indeed disappear, fine-scale microcompartments remain—hidden scaffolds of order amid apparent chaos.

Effie Apostolou, a molecular biologist at Weill Cornell Medicine who was not involved in the research, praised the study for revealing “new and surprising aspects of mitotic chromatin organization.” She noted that it highlights the “fine-scale ‘microcompartments’—nested interactions between active regulatory elements—maintained or even strengthened during mitosis.”

The Unexpected Spark of Gene Activity

The persistence of microcompartments may also help explain another biological mystery: a brief, surprising burst of gene transcription during cell division.

For decades, scientists assumed that gene transcription—the process of converting DNA instructions into RNA messages—completely stopped during mitosis. After all, the genome’s dense, compact form seemed inhospitable to the machinery needed for transcription.

Yet, in recent years, researchers noticed something strange. Near the end of mitosis, cells experience a quick, temporary spike in gene transcription. No one knew why.

Now, the MIT team believes they’ve found a clue. Microcompartments tend to cluster near the genes that show this spike. As chromosomes compact, enhancers and promoters are pressed closer together, increasing the chance that they’ll connect—and accidentally trigger brief bursts of transcription.

“It almost seems like this transcriptional spiking in mitosis is an undesirable accident that arises from generating a uniquely favorable environment for microcompartments to form during mitosis,” Hansen explains. “Then, the cell quickly prunes and filters many of those loops out when it enters G1,” the phase that follows cell division.

In essence, the very act of organizing DNA for division may unintentionally create the perfect conditions for a short-lived wave of gene activity.

How the Genome Remembers

Perhaps the most fascinating implication of this research is that it offers a mechanism for how cells “remember” their genetic organization across generations.

Even though most large-scale genome structures dissolve during division, microcompartments remain. These tiny bridges between regulatory regions and genes may serve as molecular bookmarks, preserving the spatial relationships that define which genes are active in a given cell type.

When division ends and the cell returns to its normal state, these microcompartments could help guide the genome in rebuilding its complex 3D architecture—essentially reminding it which loops to reestablish and which genes to switch on.

This idea bridges a long-standing gap in biology: connecting the structure of the genome with its functional output. “The findings help to bridge the structure of the genome to its function in managing how genes are turned on and off,” says Viraat Goel, the study’s lead author and a Ph.D. candidate at MIT.

A Dance Between Structure and Function

The study also hints at a broader principle in biology: that physical structure and genetic function are deeply intertwined.

As chromosomes compact and expand throughout the cell cycle, they don’t merely respond to biological needs—they help create them. The three-dimensional folding of DNA is not a passive phenomenon; it shapes gene activity, cellular identity, and ultimately, life itself.

By revealing that structural features persist even during the most intense phases of division, Hansen’s team shows that the genome’s architecture is more resilient and dynamic than previously thought. It’s not a static library but a living, flexible framework that bends, remembers, and adapts as life unfolds.

The Next Frontier

The research opens new avenues for exploration. The team now plans to study how differences in cell size and shape influence genome compaction and, in turn, gene regulation. If changes in a cell’s geometry affect its internal structure, that could explain many phenomena observed in development, disease, and aging.

“We are thinking about some natural biological settings where cells change shape and size, and whether we can perhaps explain some 3D genome changes that previously lacked an explanation,” Hansen says.

Another key question, he adds, is how cells decide which microcompartments to keep and which to discard after division—a process that could hold the key to understanding how gene expression fidelity is maintained.

A New Understanding of Cellular Continuity

The discovery that the genome retains a hidden order during mitosis redefines what it means for life to replicate itself. Even in the apparent chaos of cell division, there is continuity—threads of structure and memory woven through every loop of DNA.

It’s a humbling reminder that life’s order runs deeper than we can see. The genome, far from being dismantled during division, quietly carries its architectural wisdom from one generation to the next, ensuring that each new cell begins not from scratch, but from a blueprint rich with history.

As our tools for peering into the cell’s inner universe grow sharper, discoveries like this one reveal a truth as poetic as it is scientific: even in moments of profound change, life remembers.

More information: Dynamics of microcompartment formation at the mitosis-to-G1 transition, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41594-025-01687-2