When we think of climate change, we often picture belching smokestacks, sprawling cities, and endless highways packed with cars. But a new study has revealed something far more profound—our influence on the planet’s atmosphere may have begun long before the first Model T ever hit the road.

A team of climate scientists from multiple institutions has uncovered compelling evidence that human activity began leaving detectable marks on the stratosphere—the atmospheric layer above where weather occurs—as far back as 1885, just a few decades after the start of the Industrial Age. Their findings, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that Earth’s upper atmosphere has been whispering warnings for more than a century—and we’ve only recently learned to listen.

The Search for a Hidden Signal

The team set out to answer a deceptively simple question: If we had today’s advanced climate monitoring tools in the 19th century, how early could we have detected human fingerprints in the sky?

Their investigation led them to the stratosphere, a high and dry region of the atmosphere that lies above the turbulent troposphere where clouds form and weather unfolds. The stratosphere might seem detached from the everyday climate chaos we experience on the ground, but it holds powerful clues about long-term atmospheric change.

Unlike the lower layers of the atmosphere, the stratosphere doesn’t respond as wildly to seasonal variations or localized weather systems. That makes it an ideal barometer for slow, systemic changes—especially those driven by rising greenhouse gases.

“As greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide trap heat near the Earth’s surface, they actually cool the stratosphere,” explained one of the researchers. “This counterintuitive effect is one of the clearest fingerprints of human-caused climate change.”

Rewinding the Atmospheric Clock

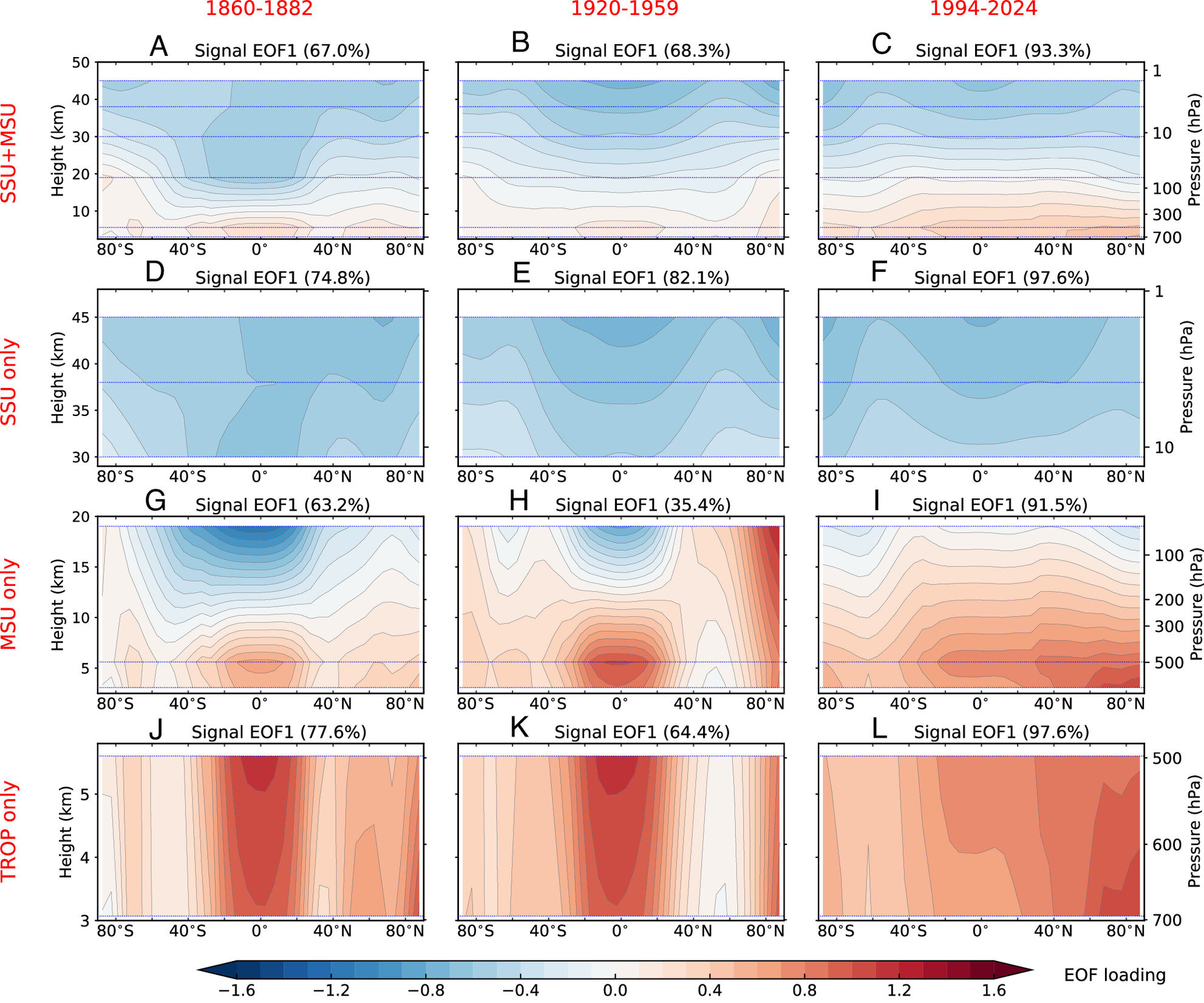

Since satellites only began scanning Earth’s atmosphere in the late 20th century, the team turned to a mix of environmental theory, historical records, and advanced computer modeling to peer back through time. They used nine sophisticated climate models—each incorporating everything from historical emissions data to the physics of atmospheric circulation—to simulate what stratospheric temperatures might have looked like as far back as 1860.

The results were striking: by 1885, just 25 years into the industrial era, the models showed that subtle but detectable cooling had begun in the stratosphere—driven not by natural variation, but by the growing human use of fossil fuels.

These changes were invisible to people at the time. There were no satellites, no climate models, and little understanding of how burning coal or wood could reshape the entire planet’s atmosphere. But with modern tools, today’s scientists can look back and clearly see what the 19th century could not.

Before Cars, Before Warnings—But Not Before Impact

The late 19th century might seem like an unlikely time for humans to have started shifting the climate. After all, automobiles wouldn’t become common for decades. But the truth is, human industry had already been burning vast quantities of coal for decades—powering factories, steamships, and city-wide heating systems. In homes and workshops, fires fueled by wood and peat had long been used for cooking and warmth.

“The misconception is that industrial-scale emissions began with the car,” one researcher noted. “But humans were altering the chemical composition of the atmosphere long before we had internal combustion engines. What we’re seeing now is just the long arc of those early beginnings.”

Indeed, people have burned things for energy for thousands of years. But the scale shifted dramatically with industrialization. As factories rose and urban centers grew, carbon dioxide—once released mostly in isolated puffs—began entering the atmosphere in torrents.

And while it took until the mid-20th century for scientists to agree that rising CO₂ levels were warming the planet, the stratosphere had already begun to record the evidence.

The Stratosphere as Witness

Part of what makes the stratosphere so valuable in climate science is its stability. Unlike the chaotic, fast-changing weather of the troposphere below, the stratosphere is more like a slow-moving river—easier to track over time.

And while surface temperatures can be affected by volcanic eruptions, solar cycles, and other short-term forces, the cooling of the stratosphere provides a steady, reliable indicator of greenhouse gas influence. This cooling has already been observed in recent decades by satellites, confirming what models and theory predicted.

But now, thanks to this new study, we know the story began much earlier.

“It’s like discovering a hidden diary from the atmosphere itself,” said one climate modeler. “All along, the stratosphere was quietly tracking the earliest signs of our impact—waiting for us to finally read the signs.”

Why This Matters Now

This research offers more than historical insight—it reframes the urgency of today’s climate crisis.

We often think of climate change as a modern problem, one born in the 20th or 21st century. But this study shows that we’ve been affecting Earth’s atmosphere for nearly 140 years. That means we’ve had a much longer runway to build up the planetary momentum we’re now struggling to slow down.

It also underscores the value of long-term data and modeling. By creating simulations that bridge the gap between history and the present, scientists can better understand the trajectory we’re on—and the window we still have to alter it.

“Climate change didn’t sneak up on us overnight,” said one co-author. “It’s the result of generations of activity. But that also means we can be the generation that changes the story.”

A Sky That Remembers

It’s humbling to realize that the atmosphere keeps records. Long before humans had the tools to measure their effect on the planet, the skies were already changing in response.

We now live in a time when satellites can track those changes in real time, and where simulations can rewind the tape to show us where we went wrong. The stratosphere remembers a time when coal smoke first drifted skyward, altering the delicate balance of sunlight, heat, and chemical flow. It remembers what we forgot—that small actions, multiplied across millions of people and years, can shift the climate of an entire planet.

Today, as we face the daunting challenges of climate mitigation and adaptation, that message echoes louder than ever. The atmosphere has been whispering to us for over a century. The question now is: are we ready to listen?

Reference: Benjamin D. Santer et al, Human influence on climate detectable in the late 19th century, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2500829122