Beneath the arid soils of northeastern Iran, where the wind sweeps across forgotten highlands and echoes of ancient trade routes linger, archaeologists have uncovered a grave that is rewriting our understanding of Bronze Age civilization. At Tepe Chalow, a site long overlooked by history, researchers led by Dr. Ali Vahdati unearthed the richest burial ever found in the Greater Khorasan Civilization (GKC)—the remains of a young woman, not yet eighteen when death claimed her, entombed with treasures that speak of status, power, and connection to a vast cultural world.

The discovery is not just about artifacts; it is about rewriting human history. For decades, scholars believed that the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)—a sophisticated Bronze Age culture—was largely confined to Central Asia’s Amu Darya basin. But Tepe Chalow told another story. “It became clear,” Dr. Vahdati recalls, “that what had once been defined as a newly recognized civilization of Central Asia was, in fact, a major cultural horizon… comparable to Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.” This was no peripheral outpost. This was part of a sweeping civilization stretching from Turkmenistan through Afghanistan and Uzbekistan into the heart of Iran, a Bronze Age powerhouse with networks reaching Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and the Persian Gulf.

The Dawn of the Greater Khorasan Civilization

Emerging at the close of the third millennium BCE, the Greater Khorasan Civilization expanded rapidly. Its people cultivated fertile deltas along the Murghab River, settled oasis regions, and carved paths through rugged Iranian valleys. By the early second millennium BCE, they had built connections that spanned thousands of kilometers. From Mesopotamian city-states to Indus Valley metropolises like Mohenjo-daro, and along the early coastal trade routes of the Persian Gulf, their goods and ideas traveled widely.

Evidence of this extensive trade is scattered across the ancient world: chlorite vessels in Iraq, lapis lazuli ornaments in Pakistan, seals and artifacts in Iran’s highlands. Ancient Mesopotamian texts speak of a land called Marhashi—a mysterious source of prized raw materials like chlorite and semiprecious stones. Archaeologists now believe Marhashi may have been this very civilization, whose influence reached far beyond what history had remembered.

The Girl in Grave 12

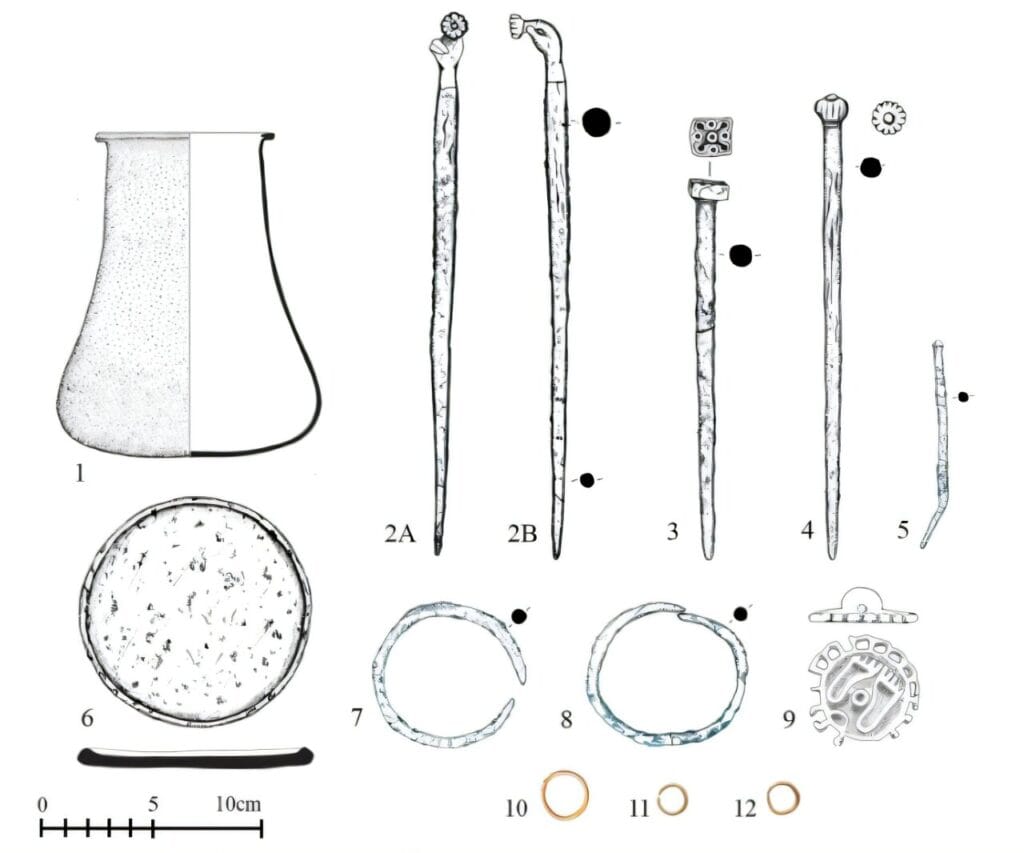

Among the graves at Tepe Chalow, one stands apart. Designated Grave 12, it cradled the remains of a teenage girl whose short life was honored with an astonishing array of grave goods—thirty-four artifacts in all. Each tells a story of artistry, wealth, and connections that bound this community to distant worlds.

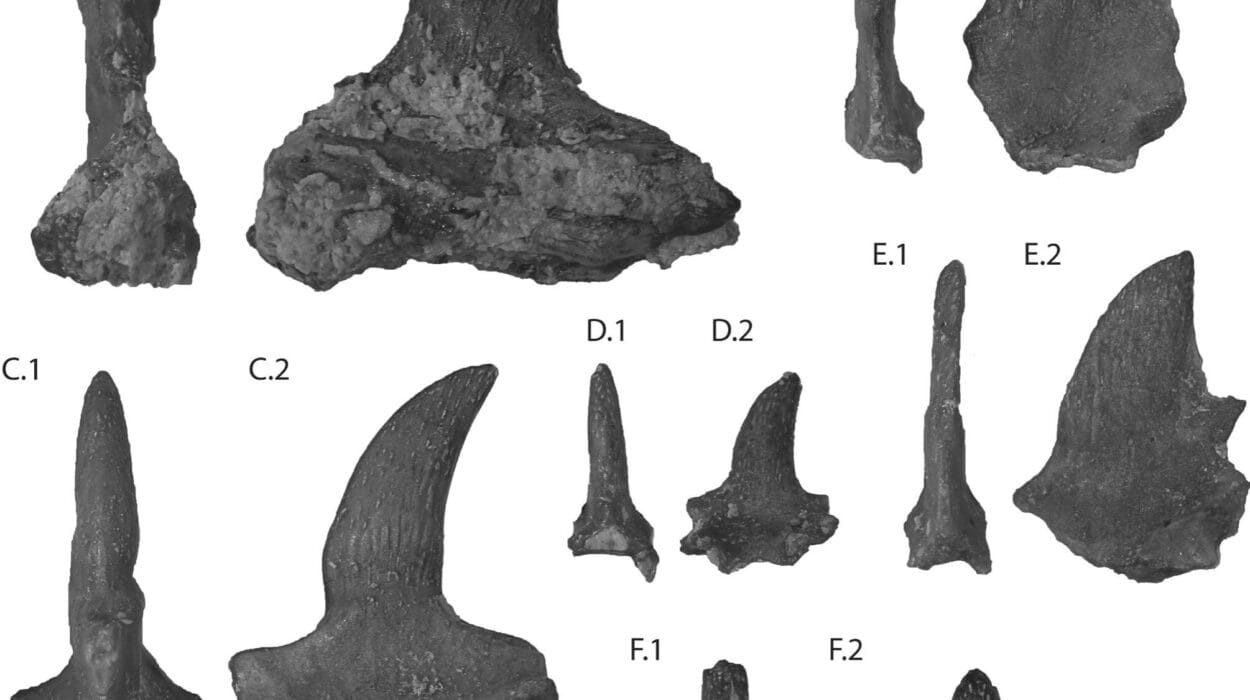

There were ivory pins, delicate gold rings, and earrings glinting with the prestige of high craftsmanship. Bronze artifacts lay beside stone vessels carved from chlorite, lapis lazuli, serpentine, and limestone. Fine pottery hinted at everyday life elevated by artistry. Among these treasures, certain objects speak louder than others: a bronze pin shaped like a hand holding a rosette, a container decorated with intertwined snakes and scorpions, and a stamp seal engraved with two human feet, a circle, and a semicircle—a symbol we may never fully decipher.

But it was not just wealth buried with her. Seals, symbols of trade and ownership, were placed with care. “The most striking element,” Dr. Vahdati explains, “is the presence of several seals… a strong indication of her active role and social standing within the Bronze Age community.” This was not a silent girl lost to history. In life, she—or her lineage—had authority, influence, and a role in networks that carried goods and ideas across the ancient world.

Women and Power in the Bronze Age

Grave 12 does more than hint at wealth; it challenges modern assumptions about gender in ancient societies. Female burials within the GKC are often richer than those of males, suggesting women may not have been relegated to secondary roles. This young woman’s lavish burial underscores a cultural structure where lineage, inheritance, and possibly leadership were shared or held by women.

Her youth raises questions. Was her status inherited? Was she destined for leadership before her untimely death? The truth is buried with her, but the evidence suggests that women of GKC were not silent figures in the backdrop of Bronze Age life—they were central, visible, and powerful in ways we are only beginning to grasp.

A Civilization of Pathways and Exchanges

Tepe Chalow was not isolated. Its location on an ancient trade corridor connected eastern Iran to the Gorgan Plain and, ultimately, the Iranian Plateau. This route, used well into medieval times, was a precursor to the Silk Roads that centuries later would link continents. The wealth in Grave 12 speaks to a community thriving on exchange—materials like ivory and lapis traveled from distant lands, passing through many hands before resting in the earth beside this young woman.

This connectivity is a defining feature of the Greater Khorasan Civilization. Unlike empires defined by conquest, this was a network of oases and settlements tied by trade, shared artistry, and a complex cultural identity that rivaled the world’s great Bronze Age powers.

Unlocking Secrets Through Science

The discovery of Grave 12 is only the beginning. Dr. Vahdati and his international team of archaeologists, anthropologists, and scientists are planning a suite of advanced analyses that will push the boundaries of what we know. Isotopic and DNA studies may reveal where this young woman was born, what she ate, and how she moved across landscapes. Technological investigations of metals, ceramics, and stone artifacts will trace their origins and manufacturing techniques, shedding light on patterns of production and exchange.

These studies are inherently collaborative, drawing expertise from anthropology, zooarchaeology, and archaeobotany to reconstruct the ecological and social environment of the time. Each artifact, each sample of soil or bone, is a fragment of a puzzle that, when assembled, reveals a picture of life in the Bronze Age that no text has preserved.

Reimagining Ancient Civilizations

What began as curiosity over scattered artifacts has become a revelation: the so-called BMAC was never confined to Central Asia. The Greater Khorasan Civilization sprawled across a vast region, bridging cultures and reshaping our understanding of ancient Eurasia. It was a civilization of artisans, traders, and visionaries, deeply connected to the great powers of Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, and yet distinctly its own.

The young woman of Tepe Chalow is not just an archaeological find. She is a voice from 4,000 years ago, reminding us that history is still incomplete, that civilizations once thought peripheral were vital, and that women in these societies played roles as complex and influential as their male counterparts.

As future studies unlock more secrets from her burial and others like it, the Greater Khorasan Civilization will continue to step out from the shadows of history. And perhaps, in time, we will know her name—not just as the girl in Grave 12, but as a symbol of a forgotten world, now remembered.

Reference: Ali A. Vahdati et al, Grave 12 at Chalow: The Burial of a Young Lady of the “Greater Khorasan Civilization”, Iran (2025). DOI: 10.1080/05786967.2025.2488251