Long before birds soared through ancient skies or mammals padded across the earth, the air belonged to a different kind of creature—one far smaller, lighter, and older. The first animals to fly were not dinosaurs or pterosaurs, but insects. Their wings, delicate and veined like stained glass, fluttered through the Carboniferous air over 300 million years ago. At a time when amphibians still crawled from the swamps and forests were composed of towering ferns and clubmosses, insects were already pushing the boundaries of evolution.

Yet even these winged pioneers were not the first of their kind. Insect evolution traces back much further, into the depths of the Devonian period, more than 400 million years ago. These earliest insects were wingless, six-legged arthropods, likely descendants of primitive crustaceans. They crept along the forest floor in silence, scavenging detritus and playing their humble part in a rapidly changing world.

From such simple beginnings would emerge dragonflies the size of seagulls, beetles with glittering carapaces, and ants with complex societies rivaling those of primates. The story of insect evolution is not merely one of ancient biology—it is a testament to survival, transformation, and triumph over the harshest forces of nature.

Born from the Sea: The Arthropod Legacy

To understand insect evolution, we must journey even deeper into the ancient past, to the Cambrian Explosion over half a billion years ago. This was a time of extraordinary biological innovation, when most major animal groups appeared in the fossil record. Among these were the arthropods, the segmented, exoskeleton-clad creatures that included trilobites, crustaceans, arachnids—and eventually, insects.

Arthropods were evolutionary pioneers. Their hard exoskeletons offered protection and support, while their jointed appendages allowed for movement, manipulation, and eventually, specialization. Some scuttled across the ocean floor, while others swam through ancient seas using flaps or paddle-like limbs.

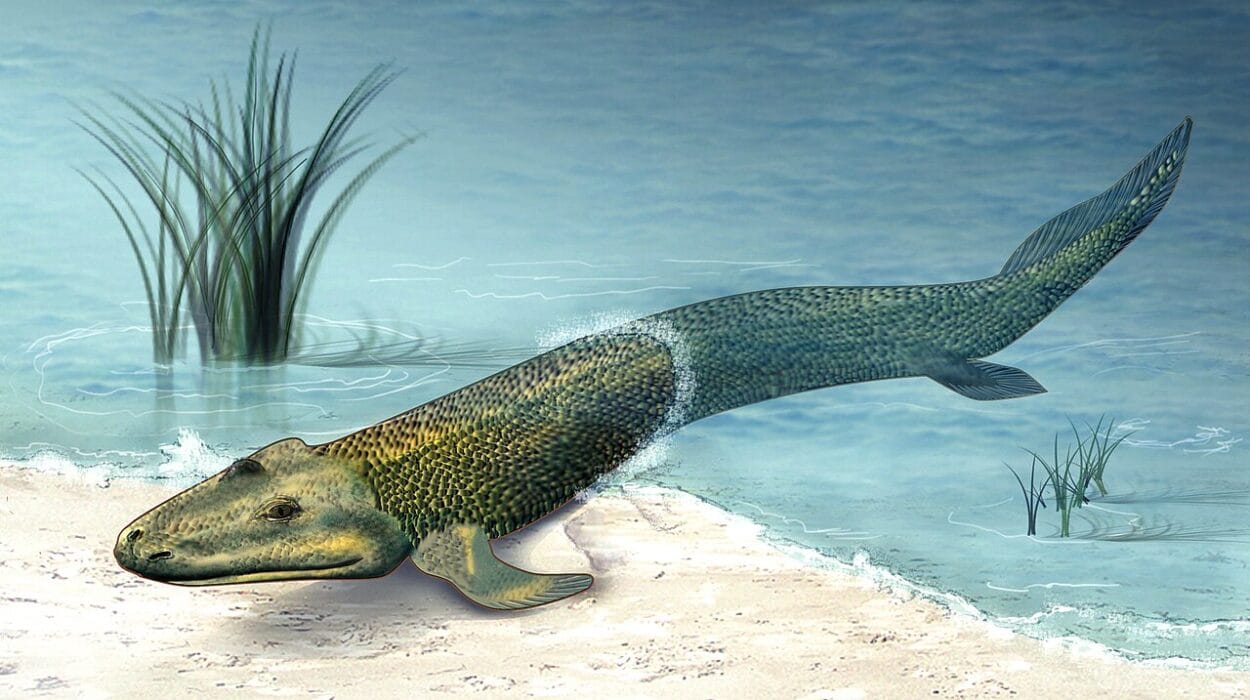

As plants began to colonize land during the Silurian and Devonian periods, some arthropods followed. The first land-dwelling arthropods were likely millipede-like detritivores, feeding on decaying plant matter. But in time, a new lineage began to take form: the ancestors of insects.

By the late Devonian, true insects had emerged. These early forms were wingless, but already showed the three-part body plan that would characterize their descendants: head, thorax, and abdomen, along with three pairs of legs. Their evolution marked a shift from water-bound life to terrestrial dominance.

Wings of Transformation: The Birth of Flight

One of the greatest mysteries in insect evolution is the origin of wings. Insects were the first animals to fly—a staggering evolutionary leap that would change the course of life on Earth.

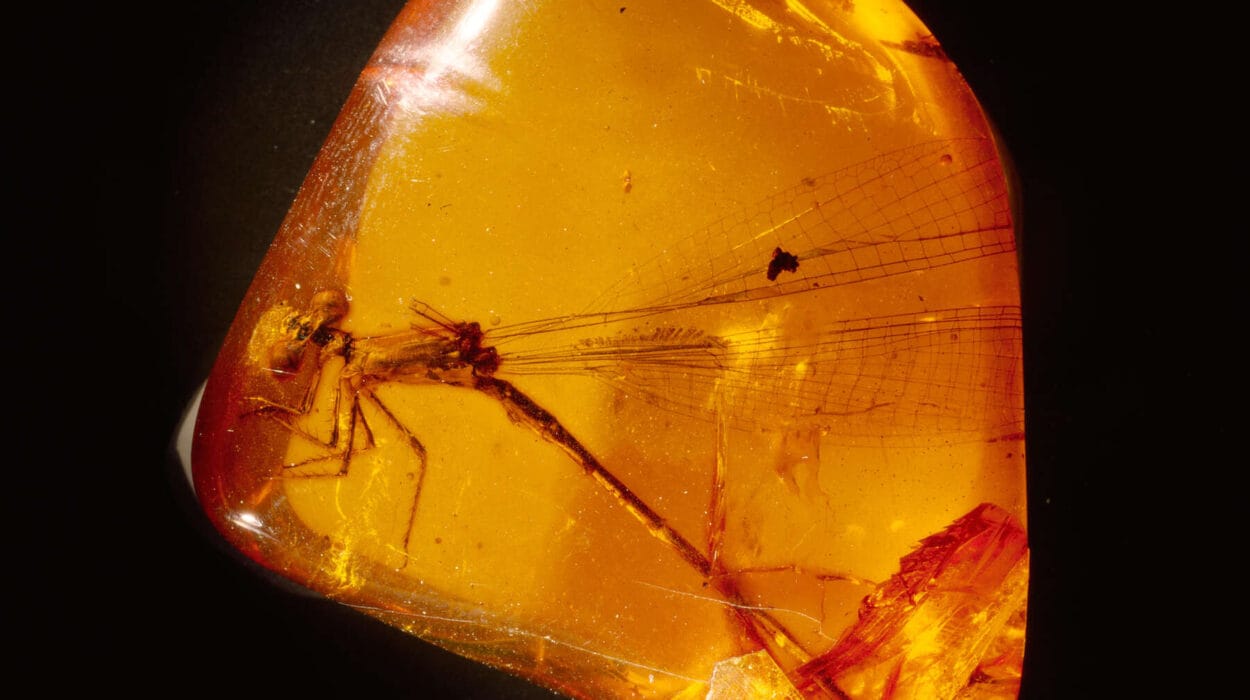

The fossil record offers a tantalizing glimpse into this transformation. By the Carboniferous period, we find well-preserved fossils of winged insects such as Meganeura, a dragonfly-like predator with a wingspan of over 70 centimeters. But how wings evolved from wingless ancestors remains a matter of scientific debate.

One leading theory suggests that insect wings evolved from gill-like appendages on the thorax of aquatic ancestors—essentially modified flaps that were used for swimming or respiration before being repurposed for flight. Another theory proposes that wings originated from extensions of the exoskeleton used for thermoregulation or display. Regardless of the precise mechanism, the result was a revolutionary adaptation.

Flight allowed insects to escape predators, seek out new food sources, and disperse over vast distances. It opened the skies, quite literally, to a new way of life. For tens of millions of years, insects were the only fliers in the animal kingdom. They had the air to themselves.

The Carboniferous Giants and Their Breathless World

The Carboniferous period, spanning roughly 359 to 299 million years ago, was a golden age for insect evolution. Vast swampy forests dominated the continents, oxygen levels soared to as high as 35%—compared to 21% today—and insects grew to monstrous sizes.

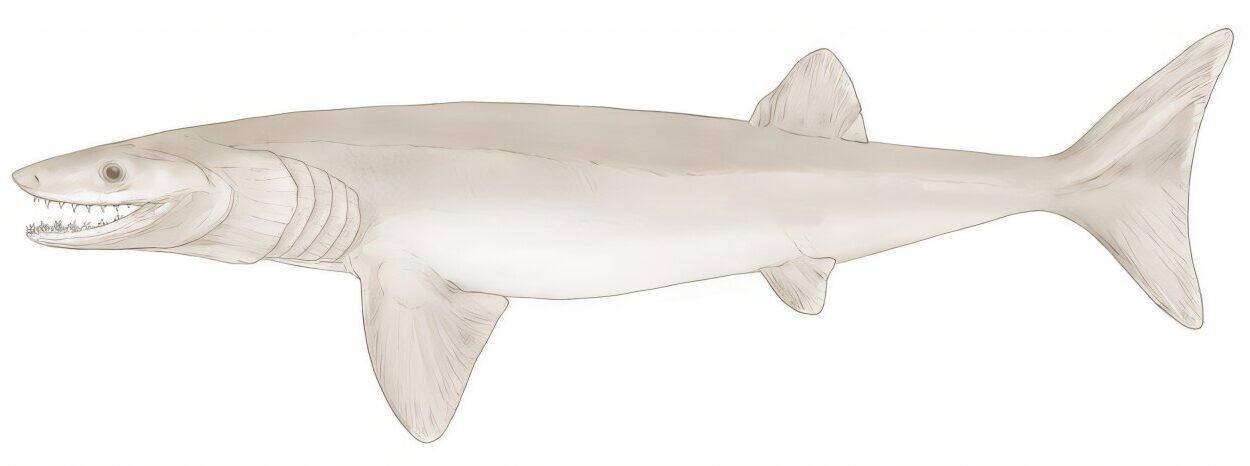

In this high-oxygen world, some arthropods reached extraordinary proportions. Arthropleura, a millipede relative, grew over two meters long. Meganeura, the giant dragonfly-like insect, hunted smaller prey with speed and precision. These creatures relied on a primitive respiratory system based on passive diffusion through tiny tubes called tracheae. Higher atmospheric oxygen allowed for larger body sizes without the need for complex lungs or circulatory systems.

But this golden age could not last. As the Permian period arrived and climate conditions shifted, oxygen levels began to fall. The once-lush forests shriveled under the effects of drying climates and massive volcanic activity. The age of insect giants came to a close. Those that survived were smaller, more adaptable, and ready for the challenges ahead.

The Metamorphic Miracle: A Second Evolutionary Revolution

If wings were the first great transformation in insect evolution, the second came in the form of metamorphosis. While many primitive insects develop through a series of incremental molts—gradually growing into adult form—advanced insects undergo a radical transformation.

Complete metamorphosis, or holometaboly, involves four distinct life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. This strategy evolved independently in several insect groups, including beetles, butterflies, flies, and bees. It proved to be an evolutionary masterstroke.

By separating the larval and adult stages, insects could specialize each phase of life for different ecological roles. Larvae could focus on feeding and growth, often in protected environments. Adults could fly, disperse, and reproduce. There was no competition between generations for food or space. Evolution had invented a kind of biological division of labor—and it worked spectacularly well.

Holometabolous insects came to dominate ecosystems. Their versatility, adaptability, and reproductive success allowed them to diversify into countless forms and fill nearly every ecological niche.

The Rise of the Beetles: Nature’s Ultimate Survivors

Among all insect groups, none have been as successful as the beetles. With over 400,000 described species—and likely millions more waiting to be discovered—beetles represent the most diverse group of organisms on Earth.

From dazzling jewel beetles to horned rhinoceros beetles, from water beetles that trap air bubbles to weevils with their elongated snouts, beetles have adapted to almost every conceivable environment.

Their success lies in part in their armored bodies and hardened forewings, called elytra, which protect their delicate flying wings beneath. This design allows them to burrow, crawl, fly, and even swim with remarkable efficiency.

The evolutionary explosion of beetles began in the Mesozoic era, as flowering plants began to diversify. Some beetles became pollinators; others fed on plant tissues or hunted smaller insects. Their fates became entwined with the plants they helped pollinate or devour—a coevolutionary dance that continues to this day.

Flowers and Pollinators: An Evolutionary Love Story

The rise of angiosperms—flowering plants—during the Cretaceous period marked another turning point in insect evolution. Flowers offered nectar, pollen, and shelter; insects offered pollination, transport, and reproduction.

Bees, butterflies, flies, and beetles evolved in tandem with these plants, developing specialized mouthparts, behaviors, and color preferences to match the blossoms they visited. In turn, flowers evolved colors, scents, and shapes that attracted their favored pollinators.

Bees, in particular, evolved highly specialized societies. Social bees, like honeybees and bumblebees, developed hives with queens, workers, and drones. They used dances to communicate the location of flowers, and they collected nectar and pollen to feed their young. In doing so, they became some of the most important ecological players in terrestrial ecosystems.

This mutually beneficial relationship transformed both partners. The floral explosion of the Cretaceous gave rise to the vibrant, buzzing world we know today—a world where butterflies flutter through meadows and humming insects visit millions of blossoms every day.

Ants and Termites: The Architects of Civilization

While bees built hives and butterflies danced among petals, other insects were busy creating vast underground empires. Ants and termites, both descended from primitive wasps and cockroach-like ancestors respectively, evolved complex social systems with astonishing degrees of cooperation.

Termites, often mistaken for ants, are master builders. They construct massive mounds that regulate temperature and humidity, allowing their fungal gardens to flourish. Inside, a single queen lays millions of eggs, while workers forage and soldiers defend.

Ants, on the other hand, have conquered nearly every terrestrial habitat on Earth. They farm aphids like cattle, use pheromones to navigate and coordinate attacks, and even go to war with rival colonies. Some species enslave other ants. Others form massive supercolonies stretching across continents.

Their success is due not only to their cooperative behavior, but also to their ability to adapt, exploit, and endure. Ants are not just insects—they are civilizations in miniature.

Survival Through Catastrophe: Insects and Mass Extinctions

The evolutionary history of life on Earth is punctuated by mass extinctions—moments when vast numbers of species vanish in relatively short periods. Insects, remarkably, have survived them all.

When the Permian extinction wiped out over 90% of marine species and many terrestrial ones, insects held on. When the asteroid struck at the end of the Cretaceous, dooming the dinosaurs and many reptiles, insects again emerged on the other side.

Part of this resilience lies in their sheer numbers and diversity. Insects reproduce rapidly, often in large numbers. Many have dormant life stages, like eggs or pupae, that can survive harsh conditions. Their small size and mobility allow them to find microhabitats where other animals cannot go.

But perhaps most importantly, insects evolve fast. Under pressure, they change, adapt, and rebound. Evolution has equipped them with the ultimate toolkit for survival.

The Human Age: Partnership and Peril

As humans spread across the globe, we brought insects with us—both willingly and unwillingly. We domesticated silkworms, bred honeybees, and used insects in agriculture and medicine. Yet we also unleashed pesticides, urbanization, and climate change.

Insects have been both our partners and our pests. Mosquitoes spread malaria and dengue; locusts devour crops; termites eat our homes. Yet without pollinators, much of our food would vanish. Without decomposers, our waste would pile up. Without insects, ecosystems would collapse.

In recent decades, scientists have sounded alarms about declining insect populations. Habitat loss, pollution, climate change, and pesticide overuse have all taken a toll. Studies show alarming drops in biomass and diversity, even in once-thriving habitats.

The evolution of insects has brought them through fire and flood, ice and asteroid. But whether they survive the Anthropocene—the human age—may depend not on their adaptability, but on our wisdom.

Epilogue: The Quiet Masters of the Earth

Insects have been on this planet for over 400 million years. They were here before the dinosaurs, before mammals, before birds. They will likely outlast us.

Their evolution is a story not just of wings and metamorphosis, but of resilience, ingenuity, and transformation. They live in deserts, jungles, caves, and mountaintops. They glow, buzz, bite, pollinate, build, and sometimes even think in ways we are only beginning to understand.

To walk through a meadow in summer, to hear the hum of bees or the chirp of crickets, is to witness a lineage more ancient than our own—a whisper from a time when wings first lifted from the forest floor and found the sky.

Insects remind us that greatness is not always measured in size, strength, or intelligence. Sometimes, it lies in adaptation, in diversity, in the quiet, persistent beating of wings.

They are the unsung engineers of life on Earth. Their story is not over.

And if history is any guide, it never will be.