Beneath the surface of the Earth lies a world of silence and stone, a place where time has folded in on itself and left its impressions like fingerprints in clay. We walk above it, oblivious to the ancient secrets it holds. Yet hidden in the strata of rock and soil are the ghostly remains of creatures that once breathed, roamed, and struggled—just like us. These remnants, preserved over millions of years, are what we call fossils. Together, they form the fossil record: nature’s deep-time diary, a fragmented but profoundly rich history of life on Earth.

It’s easy to think of fossils as relics—dead things buried in stone, frozen in time and of interest only to academics with dusty brushes. But that perspective misses the majesty of what the fossil record truly is. It’s not just a catalog of extinction; it’s a chronicle of survival. It tells us how life has responded to catastrophe, adapted to change, and flourished across unimaginable eons. In that sense, the fossil record isn’t just a look backward—it’s a mirror that reflects what life is capable of, and a window into our own origins.

A Story Written in Rock

The fossil record spans more than 3.5 billion years, a stretch of time so vast it defies the human imagination. To grasp it is to step far outside the rhythms of birth and death we know, into a theater of existence where continents drift, oceans rise and vanish, and entire species flare into being and disappear like sparks.

Fossils form when the conditions are just right: when an organism dies and is rapidly buried by sediment, protected from scavengers and decay. Over time, the soft tissues rot away, but hard parts like bones, shells, or plant stems may mineralize, turning into stone themselves. Other times, organisms leave only impressions—footprints in mud that hardened into rock, or the outlines of a leaf in ancient clay. These fossils become entombed in geological layers, each stratum a page in Earth’s biography.

To read that biography, scientists use a discipline called stratigraphy, which studies the arrangement and age of rock layers. By understanding how strata stack and correlate across regions, paleontologists can map the history of life with astonishing precision. Radiometric dating adds a numerical timeline, using the decay of isotopes in volcanic ash layers to determine the age of surrounding rock. Through this marriage of geology and biology, we are able to reconstruct worlds that vanished long before our ancestors ever dreamed of fire.

From Single Cells to Dinosaur Kings

The earliest evidence of life in the fossil record is humble: microscopic mats of cyanobacteria called stromatolites, dating back over 3.5 billion years. These simple organisms were the architects of Earth’s first major transformation. By photosynthesizing, they released oxygen into the atmosphere, paving the way for complex life.

For billions of years, life remained microscopic. Then, around 541 million years ago, the Cambrian Explosion changed everything. Suddenly, the fossil record bursts with diversity—trilobites, mollusks, primitive chordates. For the first time, we see the roots of modern animal groups, preserved in exquisite detail in places like the Burgess Shale of Canada and the Chengjiang fauna of China. These fossils reveal bizarre creatures that look like alien experiments—hallucigenia with its spikes and legs on both sides, or anomalocaris with its circular mouth and grasping limbs.

As time marched on, life grew more complex and ecosystems more intricate. Jawed fish emerged, followed by the first land plants and arthropods. Amphibians crawled onto land, and reptiles evolved from them, leading eventually to the age of the dinosaurs.

The fossil record gives us not just bones but drama—predation, competition, mass migrations, and extinction events. It shows us towering giants like Argentinosaurus, over 100 feet long, and feathered predators like Velociraptor, stalking their prey in what is now desert. These were not monsters—they were animals, born and bred in the crucible of evolution, perfectly adapted to their time and place.

Extinctions and Rebirths

But the fossil record is also a graveyard. Over 99% of all species that have ever lived are now extinct. Some vanished gradually as climates shifted or ecosystems changed. Others were erased suddenly in mass extinctions—five major ones, to be exact.

The most infamous is the one that killed the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago, likely triggered by an asteroid impact that darkened the sky and plunged the world into ecological chaos. But that wasn’t the worst. The Permian-Triassic extinction, 252 million years ago, wiped out about 90% of marine species and 70% of land species. It’s often called “The Great Dying,” and it nearly ended complex life altogether.

Yet the fossil record also tells a story of resilience. After each cataclysm, life rebounded. Mammals, once small and shadowy, exploded in diversity after the dinosaurs fell. Birds took to the skies. Flowering plants transformed the landscape. Primates emerged, and eventually, one species began shaping the world in ways no other had before.

The Human Chapter

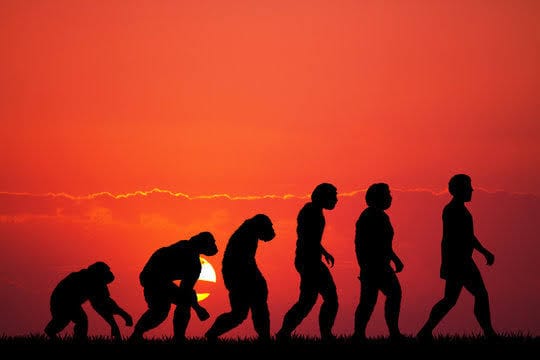

Humans are a tiny blip in the fossil record—our genus, Homo, is barely over 2 million years old. Yet the fossil evidence of our lineage is rich and poignant. From the footprints of Australopithecus afarensis in Laetoli, preserved in volcanic ash over 3.6 million years ago, to the nearly complete skeleton of “Turkana Boy,” a young Homo erectus found in Kenya, our story is written in stone.

Each fossil discovery fills in the gaps: how we stood upright, developed tools, migrated across continents. Skulls reveal brain growth, teeth record diet, and bones hint at social behaviors. We see the evolution of compassion in the healed injuries of ancient hominins, who could not have survived without the care of others. We see migration patterns in the remains of early modern humans who left Africa to populate the globe.

The fossil record grounds our myths. It tells us we did not spring into existence fully formed, but emerged from the same evolutionary forces that shaped every creature before us. We are not separate from nature—we are nature, made conscious.

A Record Under Threat

For all its richness, the fossil record is incomplete. Fossilization is rare, and preservation is biased. Soft-bodied organisms are underrepresented, and environments like forests or mountains rarely yield fossils because of erosion or lack of sediment deposition. The result is a patchy, selective window into the past.

Moreover, human activity now threatens both fossil sites and the science that studies them. Illegal fossil trade, looting, urban development, and climate change all endanger key deposits. Some fossils are stolen and sold to private collectors, removing them from scientific study forever. Others are destroyed by construction or mining before they can even be documented.

But perhaps the greatest threat is indifference. In an age of instant gratification and digital distractions, the slow, methodical science of paleontology can struggle for attention. And yet, its insights have never been more relevant.

Why the Fossil Record Matters

The fossil record matters because it gives us context. It shows us that change is the rule, not the exception. It teaches us that extinction is a natural process—but also that it can be accelerated by environmental stress, climate shifts, or sudden shocks. In a time when human-driven extinction rates rival those of past mass extinctions, this knowledge is both sobering and empowering.

It matters because it humbles us. The grandeur of geologic time dwarfs our brief history. Mountains rise and fall in the blink of an evolutionary eye. What seems permanent—cities, nations, even species—is ephemeral in the long view. Fossils remind us that Earth is not ours to dominate, but to share and steward.

The fossil record also inspires awe. It connects us to a deep narrative, one that stretches back through trilobites and dinosaurs to the first spark of life. It fills us with wonder to hold in our hands a stone that was once a living creature, to gaze into the spiral of an ammonite and feel the pull of a vanished ocean.

And it matters because it continues to evolve. New techniques—like CT scanning, synchrotron imaging, and isotopic analysis—allow scientists to peer inside fossils without damaging them, revealing muscles, nerves, even pigments. Ancient DNA is helping rewrite family trees. And new fossil finds—sometimes by amateurs walking their dogs—keep overturning what we thought we knew.

A Living Legacy

To study the fossil record is to engage in a conversation across eons. It is not merely a scientific pursuit, but a deeply human one. It speaks to our need for meaning, our drive to understand where we came from, and our responsibility for what comes next.

Every fossil is a memory—of a world that once was, of a life that once burned bright. And though the record is incomplete, its fragments form a mosaic that tells the greatest story ever told: the story of life on Earth.

In a time when we face unprecedented environmental challenges, the fossil record offers more than warnings. It offers hope. Life has endured cataclysm and reinvented itself again and again. We are part of that resilience. But unlike any other species, we can now choose what future fossils will say about us.

Will they speak of a species that consumed until the world broke? Or of one that awakened in time to protect what was left and nurture what could still be? The stone has not yet set. The next chapter is still being written.

And the fossil record—silent, ancient, enduring—will remember.