Around 151 million years ago, long before Australia became the sunburnt land we know today, its landscape was a patchwork of lakes, forests, and freshwater ecosystems teeming with life. In these calm Jurassic waters, a tiny fly once hovered and anchored itself to submerged rocks, unaware that it would one day become a silent messenger from prehistory.

Today, that ancient creature has resurfaced in the form of a fossil, found deep within the Talbragar fish beds of New South Wales. The discovery, led by researchers from the Doñana Biological Station (EBD-CSIC) in Spain and published in Gondwana Research, has astonished scientists across the globe. It represents the oldest known member in the Southern Hemisphere of the Chironomidae family—non-biting midges that thrive in freshwater environments to this day.

Named Telmatomyia talbragarica, meaning “fly from the stagnant waters,” this newly described species offers remarkable insight into the deep evolutionary past of freshwater insects and may even rewrite what we know about where this lineage began.

The Oldest Southern Chironomid

The Chironomidae family—often called “non-biting midges”—is one of the most widespread and ecologically significant groups of insects on Earth. They play a crucial role in freshwater ecosystems, serving as food for fish and amphibians and helping to recycle organic material. Yet their evolutionary history has been frustratingly incomplete, especially in the Southern Hemisphere.

The fossil of Telmatomyia talbragarica changes that. It is the oldest record of its kind ever found below the equator, dating back to the late Jurassic period—approximately 151 million years ago. Its presence in what was then part of the southern supercontinent Gondwana challenges previous theories suggesting that this group originated in the Northern Hemisphere and later dispersed southward.

According to lead author Viktor Baranov of the Doñana Biological Station, “This fossil, which is the oldest registered find in the Southern Hemisphere, indicates that this group of freshwater animals might have originated on the southern supercontinent of Gondwana.”

A Unique Evolutionary Adaptation

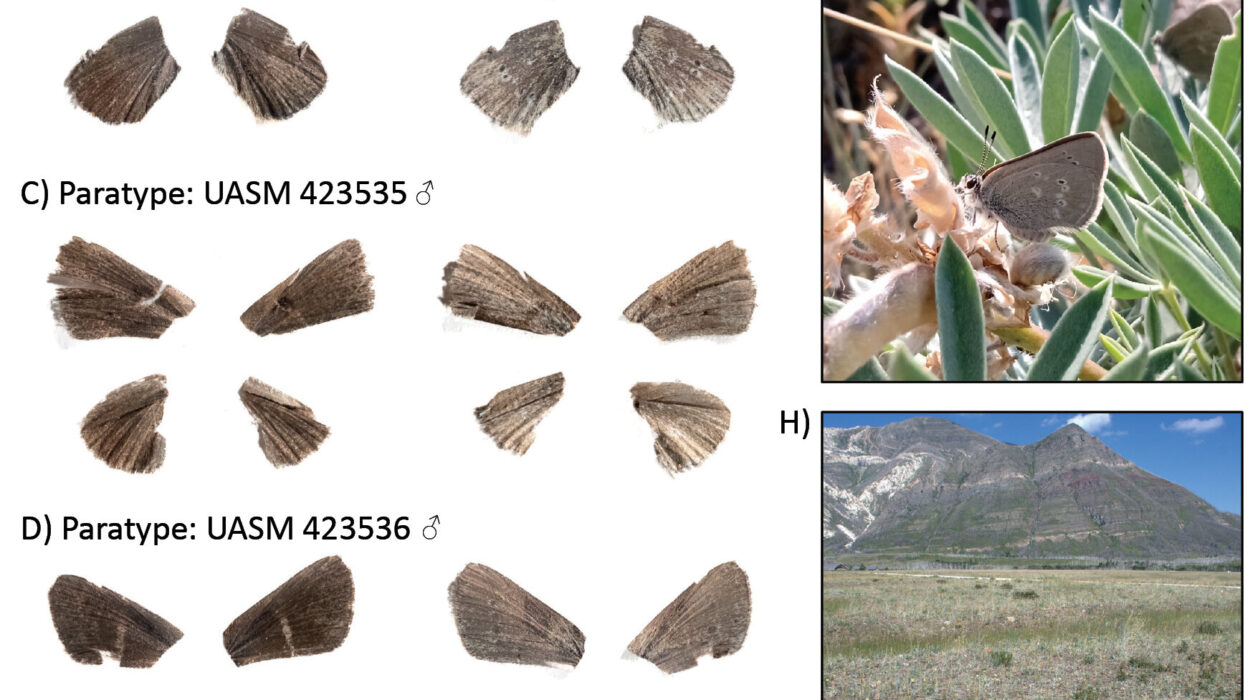

What makes this discovery particularly intriguing is not just its age, but its anatomy. The fossilized specimens—six in total, including both pupae and adults—revealed an extraordinary adaptation: a terminal disk, a small structure likely used to cling to rocks or other submerged surfaces.

Such mechanisms are usually seen in marine organisms that need to resist tides and waves. Finding this feature in a freshwater species surprised researchers, suggesting that Telmatomyia talbragarica evolved a similar strategy independently—a striking example of evolutionary convergence and adaptability.

“The sedimentological and paleontological evidence clearly indicates that the Talbragar environment was freshwater,” the researchers noted. “This highlights the remarkable phenotypic plasticity displayed by chironomids.”

In other words, this little fly had evolved the flexibility to survive where others couldn’t, using a tool previously thought to exist only in ocean-dwelling creatures.

From Ancient Lakes to Modern Theories

The Talbragar fish beds are one of Australia’s most important fossil sites. The area preserves a Jurassic lake ecosystem frozen in time, filled with ancient fish, plants, and now—thanks to this discovery—a tiny insect that bridges continents and eras.

The international research team, including scientists from the Australian Museum Research Institute, the University of New South Wales, the University of Munich, and Massey University in New Zealand, used advanced imaging techniques to study the delicate fossils. Their findings don’t just add a new species to the fossil record; they challenge long-standing theories about how and where key insect groups evolved.

For decades, scientists believed that the Podonominae subfamily of midges, to which this species belongs, originated in the Northern Hemisphere. Older Jurassic fossils from Eurasia seemed to support that theory. But Telmatomyia talbragarica provides powerful evidence pointing the other way—that these insects may have first appeared in Gondwana before spreading northward.

Rewriting the Biogeography of Insects

Podonominae midges have fascinated biologists for decades because their global distribution offers clues about continental drift and the breakup of ancient landmasses. Today, these midges are found almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere—in places like South America, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

This pattern reflects a process called vicariance—when a species becomes divided by a new geographical barrier, such as a mountain range or an ocean, forcing populations to evolve independently. The renowned Swedish entomologist Lars Brundin proposed in 1966 that the ancestors of these insects were once widespread across Gondwana and became separated as the supercontinent fractured.

The new fossil evidence strongly supports Brundin’s hypothesis. If these midges did originate in Gondwana, their descendants’ present-day distribution is a living echo of ancient continental movements.

“The fossil helps us interpret how Southern Hemisphere biotas formed and changed through geological time,” explains Steve Trewick, professor at Massey University. “Tiny, delicate freshwater insects like the Talbragar fly are rare in the fossil record, and every specimen adds a crucial piece to the puzzle of life’s history.”

A Tale of Discovery and Scarcity

Despite its importance, the discovery also underscores a persistent problem in paleontology: the unevenness of the fossil record. While Northern Hemisphere fossils have been extensively studied, the Southern Hemisphere remains relatively unexplored, particularly for small, fragile organisms like insects.

“There is a strong bias towards finding and studying fossils in the Northern Hemisphere,” says Matthew McCurry, paleontologist from the Australian Museum and the University of New South Wales. “Because of this, we end up making incorrect assumptions about where groups originated.”

Until now, only two Podonominae fossils had ever been documented from the Southern Hemisphere—one from the Eocene of Australia and another from the Paleocene of India. The Telmatomyia talbragarica fossils push that record back by over 100 million years, offering a new anchor point for understanding how these insects evolved.

Unlocking Evolutionary Mysteries

The research team believes that combining fossil evidence with modern genetic data could reveal how these insects dispersed after the breakup of Gondwana. Were they passive travelers, carried by winds and water currents? Or were they active colonizers, expanding into new habitats on their own?

Answering these questions could help scientists understand not just ancient insect evolution, but also how modern biodiversity responds to environmental change. Fossils like Telmatomyia talbragarica act as time capsules, preserving biological strategies that once worked in a world very different from ours—and perhaps offering lessons for the one we’re changing today.

The Echo of Ancient Wings

It’s easy to overlook the significance of a fossil the size of a pinhead. Yet, in the quiet layers of the Talbragar rocks, that tiny fly carries the story of an entire lineage—how life adapts, migrates, and endures through epochs of transformation.

This discovery reminds us that even the smallest creatures can illuminate the grandest patterns of life on Earth. The midges buzzing over our ponds and lakes today are not just insects—they are the living descendants of survivors from a world 150 million years gone.

From the stagnant waters of Jurassic Australia to the flowing rivers of our present world, the story of Telmatomyia talbragarica speaks of resilience, adaptation, and the enduring creativity of evolution.

A Legacy Written in Stone

In every fossil lies a story written not in ink, but in the language of time. The discovery of Telmatomyia talbragarica does more than fill a gap in the fossil record—it challenges us to rethink where life came from and how it spread across the planet.

It is a reminder that even the smallest traces of ancient life can shift our understanding of evolution’s grand narrative. Long after the Jurassic lakes dried and the continents drifted apart, this fragile insect endures as a bridge between worlds—a fossil whispering across 151 million years that life, in all its forms, will always find a way to cling to the rock of existence.

More information: Viktor Baranov et al, The oldest Gondwanan non-biting midge (Diptera, Chironomidae, Podonominae) sheds light on the historical biogeography of the clade, Gondwana Research (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.gr.2025.09.001