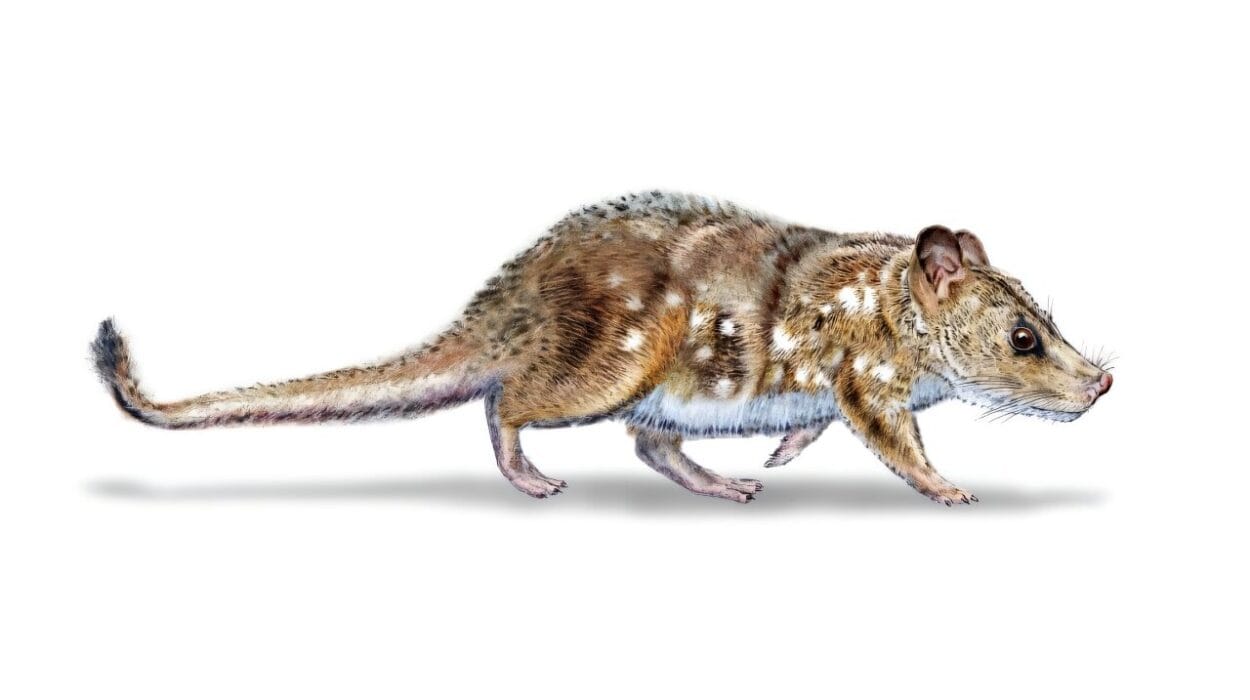

For more than two decades, a nearly complete skeleton lay at the center of one of paleoanthropology’s most persistent debates. Dug slowly and painstakingly from the ancient rock of South Africa’s Sterkfontein Caves, the fossil known as “Little Foot” seemed, at first, to offer something rare and reassuring: clarity. Unlike most fragments of early human ancestry, this skeleton was astonishingly intact, a near-whole body from a distant past. Yet instead of settling arguments about our origins, Little Foot has continued to provoke them, quietly challenging scientists to reconsider what they thought they knew.

Now, a new international study led by researchers from Australia’s La Trobe University and the University of Cambridge has reopened the question of who Little Foot really was. Published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, the research suggests that this fossil may not belong to any known species of Australopithecus at all. Instead, it may represent a previously unidentified human relative, one that forces a fresh look at how many kinds of early humans once walked southern Africa.

The Long Journey Out of Stone

Little Foot’s story began in 1998, when fragments of bone were identified in the Sterkfontein Caves, a site already famous for yielding crucial evidence about early human ancestors. What followed was not a quick discovery but a patient, 20-year effort. Paleoanthropologist Ronald Clarke led the excavation and analysis, slowly freeing the fragile bones from surrounding rock and reconstructing the skeleton piece by piece.

When the fossil was finally revealed to the world in 2017, its completeness was immediately apparent. Known formally as StW 573, Little Foot stood apart from most hominin fossils, which are often represented by isolated skulls or partial limbs. Here was an individual whose anatomy could be studied across the entire body, offering an unusually detailed glimpse into an ancient way of life.

Clarke concluded that Little Foot belonged to Australopithecus prometheus, a species name that had long been controversial. Other researchers disagreed, arguing instead that the skeleton fit within Australopithecus africanus, a species first described in 1925 by Australian anatomist Raymond Dart and already known from Sterkfontein and elsewhere in South Africa. The disagreement reflected a deeper uncertainty about how many distinct kinds of early human relatives shared this landscape millions of years ago.

When Familiar Labels Begin to Slip

The new study challenges both of those interpretations. Led by Dr. Jesse Martin, an adjunct at La Trobe University and a postdoctoral research fellow at Cambridge, the research team closely examined Little Foot’s anatomical traits. Their conclusion was striking: the skeleton does not share a unique suite of features with either Australopithecus prometheus or Australopithecus africanus.

“This fossil remains one of the most important discoveries in the hominin record and its true identity is key to understanding our evolutionary past,” Dr. Martin said. “We think it’s demonstrably not the case that it’s A. prometheus or A. africanus. This is more likely a previously unidentified, human relative.”

Rather than fitting neatly into an existing category, Little Foot seems to occupy its own anatomical space. The traits that define known species do not align cleanly with what this skeleton shows, suggesting that scientists may have been trying to force an unfamiliar form into familiar boxes.

A Vindication Decades in the Making

The implications of this reassessment extend beyond taxonomy. Ronald Clarke had long argued that more than one species of early human lived at Sterkfontein at the same time, an idea that was not universally accepted. Little Foot, according to Dr. Martin, provides strong support for that view.

“Dr. Clarke deserves credit for the discovery of Little Foot, and being one of the only people to maintain there were two species of hominin at Sterkfontein. Little Foot demonstrates in all likelihood he’s right about that. There are two species.”

This statement reframes the fossil not as an odd example of a known species, but as evidence of greater diversity among early human relatives than previously recognized. If multiple species coexisted in the same region, they may have occupied different ecological niches or followed distinct evolutionary paths, complicating any simple narrative of human origins.

The Most Complete Witness to an Ancient World

Little Foot’s significance is magnified by its completeness. Among ancient hominin fossils, StW 573 remains the most complete ever found. That completeness allows scientists to study proportions, movement, and variation in a way that fragmented remains cannot easily support.

Dr. Martin’s team is the first to challenge the species attribution of Little Foot since its unveiling in 2017. “Our findings challenge the current classification of Little Foot and highlight the need for further careful, evidence-based taxonomy in human evolution,” Dr. Martin said.

Taxonomy may sound like a dry exercise in naming, but in human evolution it shapes the stories scientists tell about where we came from. Each species name carries assumptions about relationships, behaviors, and adaptations. If Little Foot represents a distinct species, then existing models of early human diversity must be revised to accommodate it.

Rethinking Old Names and Old Ideas

Professor Andy Herries of La Trobe University emphasized just how unusual Little Foot is when compared to previously defined species. He noted that the fossil differs clearly from the type specimen of Australopithecus prometheus, a name originally defined on the idea that these early humans made fire.

“It is clearly different from the type specimen of Australopithecus prometheus, which was a name defined on the idea these early humans made fire, which we now know they didn’t. Its importance and difference to other contemporary fossils clearly show the need for defining it as its own unique species.”

This observation highlights how scientific interpretations evolve. Ideas once used to define species can later be overturned, leaving names and classifications in need of reassessment. Little Foot’s anatomy, preserved across an entire skeleton, provides an opportunity to revisit those assumptions with fresh evidence.

A New Chapter Still Being Written

The story is far from over. Dr. Martin, along with students from La Trobe University, will continue working to clarify which species Little Foot represents and where that species fits within the broader human family tree. This process will involve careful comparison with other fossils and a cautious approach to defining what truly distinguishes one species from another.

The research itself reflects a wide collaboration, bringing together institutions from the United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, and the United States. Such international cooperation underscores how questions about human origins transcend borders, drawing on expertise and perspectives from around the world.

Why Little Foot Matters Now

At its core, this research matters because it challenges simplicity. Human evolution is often imagined as a straightforward progression, one species replacing another on a single path toward modern humans. Little Foot tells a different story, one in which diversity and coexistence played a central role.

By suggesting the presence of a previously unidentified human relative, the study opens the door to a richer understanding of early human diversity in southern Africa. It implies that our ancestors were not alone, not uniform, and not easily categorized. Instead, they were part of a complex mosaic of forms, adapting in different ways to their environments.

Little Foot, silent for millions of years and patient through decades of excavation, now speaks again through careful analysis. Its message is not one of final answers, but of deeper questions. Who else lived alongside our ancestors? How many evolutionary experiments unfolded before our own lineage emerged? And how much of that ancient diversity remains hidden, waiting for scientists willing to look again at what they thought they already knew?

In raising these questions, the research reminds us that understanding our past is not about closing debates, but about keeping them alive, guided by evidence and a willingness to revise even our most cherished classifications.

More information: Jesse M. Martin et al, The StW 573 Little Foot Fossil Should Not Be Attributed toAustralopithecus prometheus, American Journal of Biological Anthropology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.70177