In the quiet Queensland town of Murgon, where sheep graze under the blazing Australian sun, there lies a humble clay pit behind a grazier’s home. To most, it looks like an ordinary patch of land—dusty, cracked, and unremarkable. But for scientists, this backyard has become one of Australia’s most extraordinary time capsules. Beneath the soil lies a treasure trove of fossils that tell the story of a continent still tethered to Antarctica and South America, some 55 million years ago.

For nearly four decades, paleontologists have been returning to this unassuming site, carefully peeling back layers of clay to reveal fragments of ancient life. Among the finds are fossils of mammals, snakes, frogs, and even the world’s oldest-known songbirds. And now, a team led by the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP) and researchers from UNSW Sydney has added another piece to this prehistoric puzzle—the oldest crocodilian eggshells ever found in Australia.

Discovering the Oldest Crocodile Eggs in Australia

The discovery, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, brings to light eggshell fragments that belonged to a long-extinct group of crocodiles known as mekosuchines. These ancient crocs ruled Australia’s inland waterways more than 50 million years ago—long before today’s familiar saltwater and freshwater crocodiles arrived from Southeast Asia roughly 3.8 million years ago.

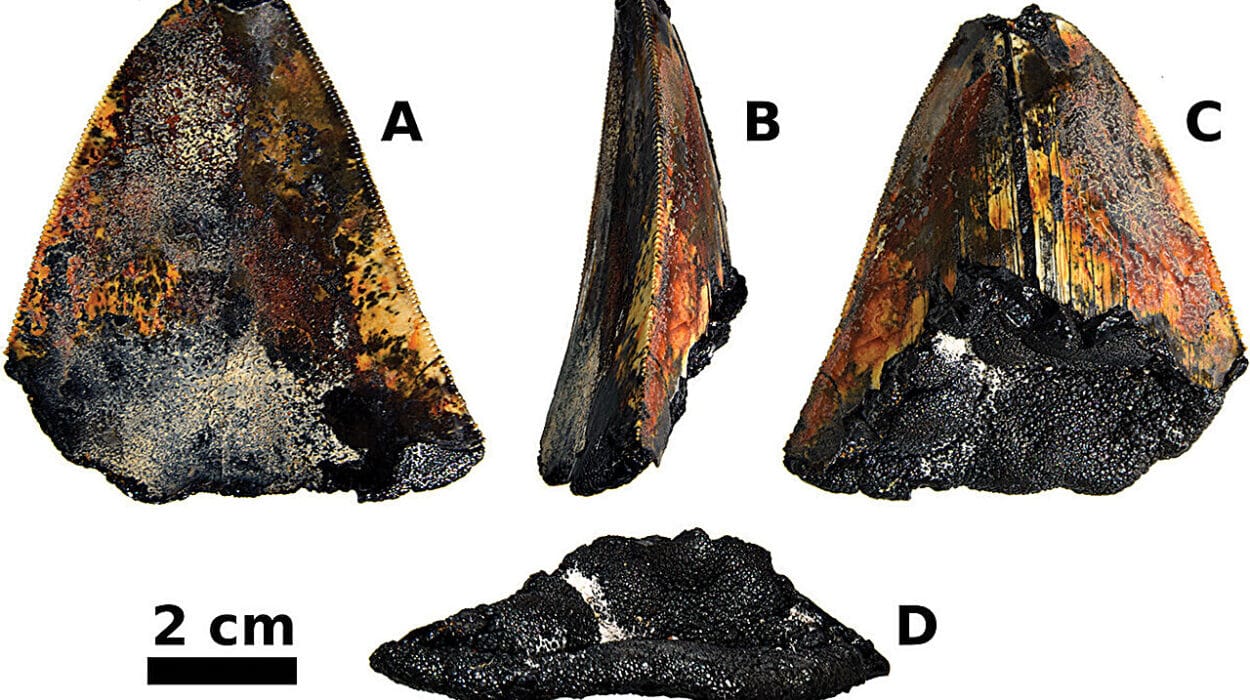

The fossilized eggshells, named Wakkaoolithus godthelpi, offer a rare glimpse into the reproductive life of these forgotten reptiles. For paleontologists like lead author Xavier Panadès i Blas, they are more than just fragments of shell—they are windows into the private lives of animals that once stalked the forests and rivers of ancient Australia.

“These eggshells have given us a glimpse of the intimate life history of mekosuchines,” Panadès i Blas explains. “We can now investigate not only the strange anatomy of these crocs but also how they reproduced and adapted to changing environments.”

Crocodiles That Climbed Trees

Unlike modern crocodiles, which mostly lurk in rivers and swamps, mekosuchines were an extraordinarily diverse and adaptable group. They filled ecological roles unlike any reptiles alive today. Some species were small and land-dwelling, while others may have hunted in forests rather than waterways.

UNSW paleontologist Professor Michael Archer describes them with a kind of gleeful disbelief. “It’s a bizarre idea,” he says, “but some of them appear to have been terrestrial hunters in the forests.”

Even more astonishing are the “drop crocs”—semi-arboreal species that, according to fossil evidence, may have climbed trees and leapt down on unsuspecting prey below. Archer likens them to reptilian leopards. “They were perhaps hunting like big cats—dropping out of trees on any unsuspecting thing they fancied for dinner,” he says.

Such behavior challenges our assumptions about crocodiles, painting a picture of ancient ecosystems filled with agile, cunning predators unlike anything in Australia today.

Eggshells as Time Machines

Eggshells, though fragile, can outlast even bones when buried under the right conditions. They act as micro time capsules, preserving not only their structure but also geochemical clues about their environment.

“Eggshells are an underused resource in vertebrate paleontology,” says Panadès i Blas. “They preserve microstructural and geochemical signals that tell us not only what kinds of animals laid them, but also where they nested and how they bred.”

Using high-powered optical and electron microscopes, the team examined the Murgon shells in astonishing detail. Their findings suggest that the mekosuchine crocodiles laid their eggs along the shores of ancient lakes, adapting their reproductive strategies to the region’s shifting climate.

Co-author Dr. Michael Stein notes that these ancient crocs faced tough times as Australia’s interior grew drier. Over time, their habitats shrank, forcing them to compete for dwindling resources and waterways. Eventually, their inland empire disappeared, and with it, the mekosuchines themselves.

A Lost World Beneath the Forest Canopy

Fifty-five million years ago, the Murgon region was a lush rainforest, filled with strange and wondrous creatures. “This forest was home to the world’s oldest-known songbirds, Australia’s earliest frogs and snakes, and small mammals with South American connections,” Dr. Stein says. “It even hosted one of the world’s oldest-known bats.”

Each fossil found at Murgon adds to this vivid picture of an ancient ecosystem teeming with life. The discovery of the crocodile eggshells doesn’t just tell us about the crocs—it ties into a much broader story about how life evolved on a young continent still finding its identity.

A Jaw That Shocked the Experts

Professor Archer’s connection to these prehistoric crocodiles goes back decades. In 1975, he uncovered a strange reptilian jaw in the Texas Caves of southeastern Queensland. At first, he didn’t recognize it as belonging to a crocodile—it seemed too unusual. Seeking answers, Archer consulted Max Hecht, a reptile specialist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

“When he saw it, Max nearly dropped his coffee cup,” Archer recalls with a laugh. “It closely resembled another kind of extinct croc with dinosaur-type teeth that had been found in South America.”

That jawbone marked a turning point—it revealed that ancient crocodiles with dinosaur-like teeth once lived in Australia, part of a lineage that linked the continent to its prehistoric neighbors across the southern hemisphere.

The Backyard That Changed Paleontology

Eight years after that discovery, Archer and his colleague Henk Godhelp drove to Murgon to investigate reports of fossil turtle shells. “We parked on the side of the road, grabbed our shovels, knocked on the door, and asked if we could dig up their backyard,” Archer says.

The homeowners, intrigued and amused, said yes—and soon, their sheep paddock became a paleontological gold mine. Fossils from that site have since revealed some of the earliest evidence of modern Australian fauna, from mammals and birds to reptiles and amphibians.

It was from this very deposit—the Tingamarra site—that the ancient crocodile eggshells were uncovered. And according to Archer, the discoveries are far from over. “From the many fascinating animals we’ve already found in this deposit since 1983,” he says, “we know that with more digging there will be a lot more surprises to come.”

Lessons from the Past for a Fragile Future

For Professor Archer, unearthing fossils is not just about looking back—it’s about learning how to protect what remains. Ancient bones and eggshells tell stories of adaptation and extinction, lessons that are deeply relevant as today’s species face the accelerating impacts of climate change.

Archer’s ongoing Burramys Project is a living example of this philosophy. The initiative aims to save the endangered Mountain Pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus), a tiny marsupial native to Australia’s alpine regions. Once thought to be confined to cold mountain habitats, fossil evidence uncovered by Archer’s team revealed that its prehistoric relatives thrived in lowland rainforests millions of years ago.

This discovery inspired a daring conservation experiment: reintroducing the possum to lowland rainforest environments. Working with Secret Creek Sanctuary and supported by organizations such as Prague Zoo, Archer’s team established a breeding population near Lithgow, New South Wales. Against all odds, the possums flourished—just as the fossil record predicted they would.

“The Burramys Project shows that not all stories about climate change need to end in despair,” Archer says. “Sometimes, the past can point the way to solutions for the future.”

The Echo of Deep Time

In the clay beneath a Murgon backyard lies a story that stretches across eons—from the time when Australia was still part of a supercontinent to the moment a paleontologist knocked on a door with a shovel in hand. The discovery of the world’s oldest crocodilian eggshells adds another chapter to that story—a reminder that every fragment, no matter how small, can rewrite what we know about life on Earth.

These eggs, laid on the shores of an ancient lake, now whisper across 55 million years to tell us that life endures, adapts, and evolves. They remind us that the ground beneath our feet is alive with memory—and that the key to our future may yet lie buried in the past.

More information: Xavier Panadès I Blas et al, Australia’s oldest crocodylian eggshell: insights into the reproductive paleoecology of mekosuchines, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2025.2560010